Energized by a climate of opportunity and a burst of positive attention for the region, civic leaders in the Shoals have launched a new effort to improve the economy and quality of life through cross-community collaboration.

More than 150 people attended the launch of the effort, which is organized by the Committee for a Greater Shoals, a group of Shoals business leaders. The event featured the release of A Greater Shoals: a Pathway, a report authored by PARCA on the current state of the region and avenues of opportunity.

Shortly after the event, 110 people had signed up for one or more of six committees:

- Broadening the Definition of Economic Development

- Developing High-Tech Infrastructure/Recruiting

- Quality of Life

- Workforce Development and Education

- Unified Tourism

- Government Cooperation and Structure.

Off the Interstate corridor and tucked away in the Northwest corner of the state, the Shoals is often described by residents as a well-kept secret. That is part of the region’s charm, but it’s also a frustration.

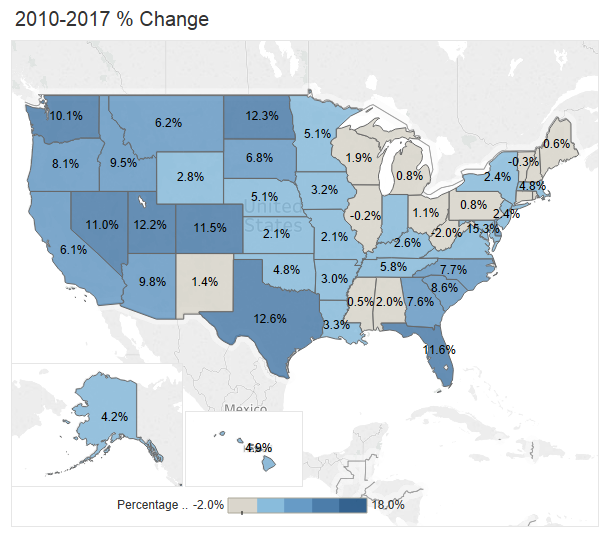

Taken together, the four cities at the heart of the Shoals — Florence, Muscle Shoals, Sheffield, and Tuscumbia — have a population of over 70,000. A combination of the four adjacent cities would rank as Alabama’s 7th largest city. Leaders in the Shoals have long wondered if the region was held back by the fragmented nature of the Shoals, with four principal cities, and six school systems spread across two counties.

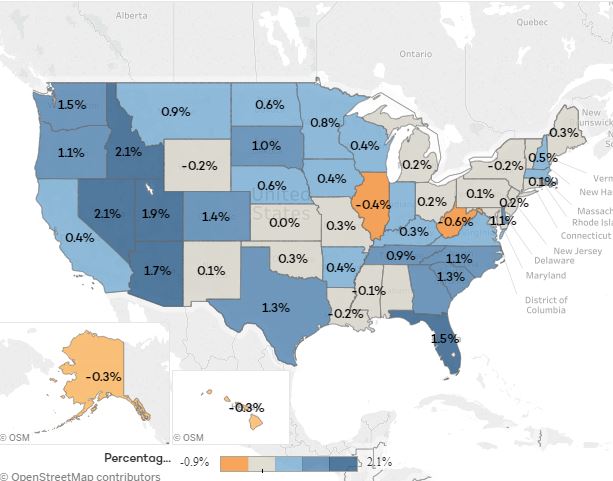

Building off research PARCA performed on the Birmingham metro area, PARCA found evidence that fragmentation did have discernable negative effects in the Shoals but also identified cooperative structures the Shoals has developed to pull the region together.

The report recommended building on those existing cooperative structures to capitalize on immediate

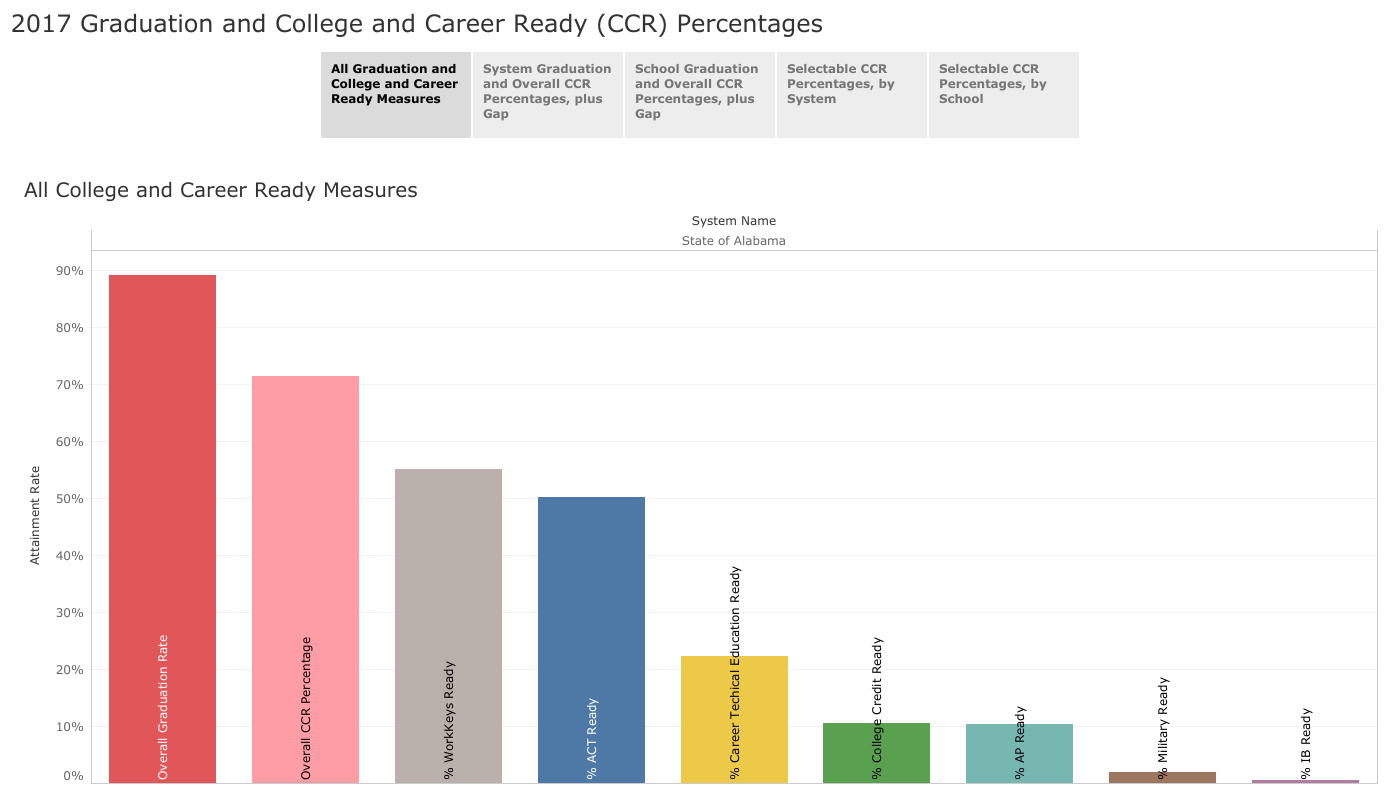

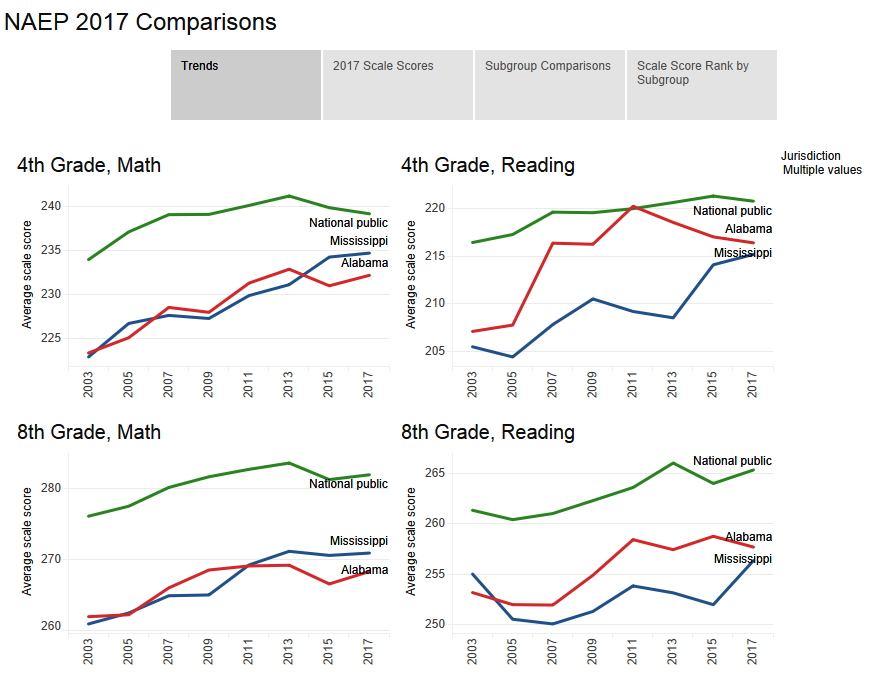

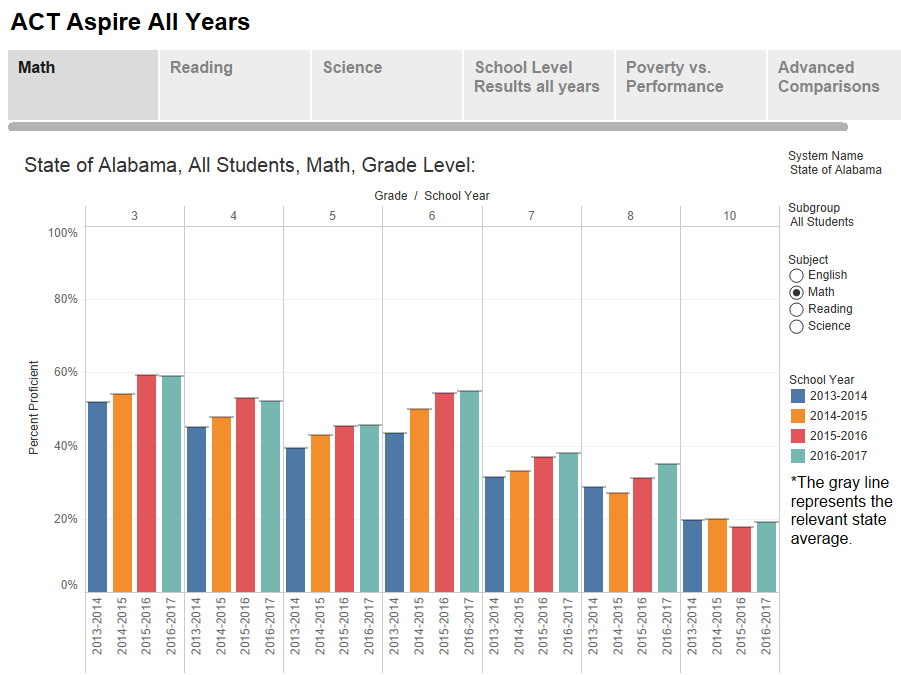

The report found success to build on in the area of education. According to PARCA’s analysis, when the K-12 school systems in the Shoals metropolitan area were considered together, they produce a higher college and career readiness rate among high school seniors than any other Alabama area.

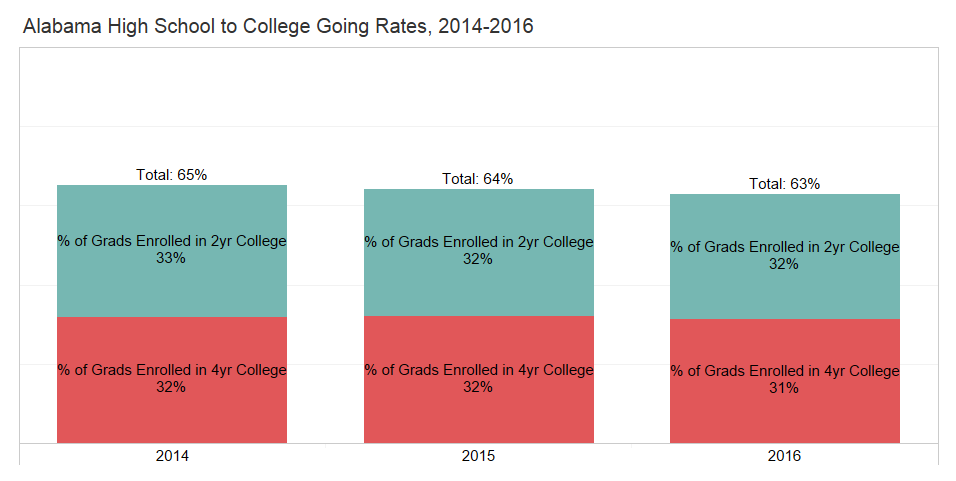

The Shoals also has the second highest college-going rate among Alabama MSAs, thanks in part to a local civic initiative, Shoals Scholar Dollars, that provides scholarships for residents of Colbert and Lauderdale counties. The Shoals is home to a community college, Northwest-Shoals Community College, and a four-year university, the University of North Alabama, both of which are poised for growth.

The Shoals has developed vehicles for bringing its counties and cities together in pursuit of economic development, including a unified economic development authority, a unified economic development fund, and a united two-county Chamber of Commerce.

Those cooperative structures create a strong competitive position for the Shoals in pursuing industrial projects, like suppliers for the Toyota-Mazda Manufacturing plant under construction in Huntsville. But they also provide a framework for cooperation on further developing the Shoals natural and cultural assets.

With the Tennessee River running through its heart, the Shoals

A coordinated cooperative effort to build on these strengths would bring more resources and reach, the report