Any effort to promote cooperation between governments quickly runs into skepticism.

Cities and their citizens are self-interested, the thinking goes. They are not going to give up their advantages. They’re not going to be charitable to a neighboring community, just for the sake of being nice.

And the skeptics are right.

However, that doesn’t foreclose opportunities for cooperation. In fact, self-interest is the starting point for cooperation.

That’s one the lessons learned on the way to the Good Neighbor Pledge, an agreement signed earlier this year by about two dozen mayors in Jefferson County. Under the agreement, mayors pledged not to encourage or incentivize the relocation of local businesses from neighboring cities to their own. In so doing, the mayors hope they’ve solved a problem all of them were facing: a growing demand and expectation that local governments provide tax incentives to retain or attract businesses.

On the surface, signers of the Pledge appear to be giving up advantages and competitive tools in economic development. However, because almost all the key governments participated, the pledge resets the rules of the game, short-circuiting counter-productive and mutually damaging competitive battles that were costing all cities time, attention, and tax dollars while providing no net benefit to the region.

This feature is part of an occasional series on creative cooperation between local governments and other civic partners. Through the series, we hope to identify, share, and spread best practices and lessons learned.

Laying the Groundwork

The Good Neighbor Pledge grew out of an effort by the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham (CFGB) to understand regional challenges and to identify options for addressing those challenges. If not for the background research and dissemination of the findings, the Good Neighbor Pledge likely would not have come about.

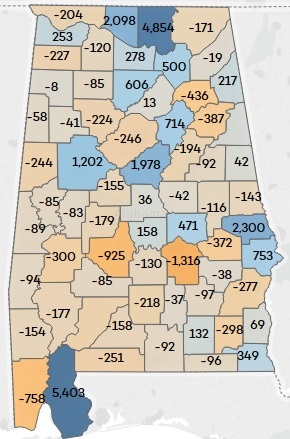

After arriving in Birmingham in 2014, CFGB president and CEO Chris Nanni kept hearing from Birmingham-area leaders that the fragmented nature of the region, 35 municipalities in Jefferson County alone, was interfering with the region’s ability to effectively address problems or pursue an over-arching vision for the community.

With funding from a key circle of the Community Foundation’s Catalyst donors, the Community Foundation commissioned PARCA to research whether Greater Birmingham’s lack of cooperation was negatively affecting its ability to compete and if so, how other cities and metros have overcome fragmentation and moved toward a more unified approach to community progress.

To help frame the issues and provide response and guidance to the study, CFGB formed a broadly-representative strategic advisory group of Birmingham area leaders who were consulted throughout the research process. After the report, Together We Can, was published, the leaders from that Strategic Advisory Group were also essential in carrying the information and conclusions out to the community.

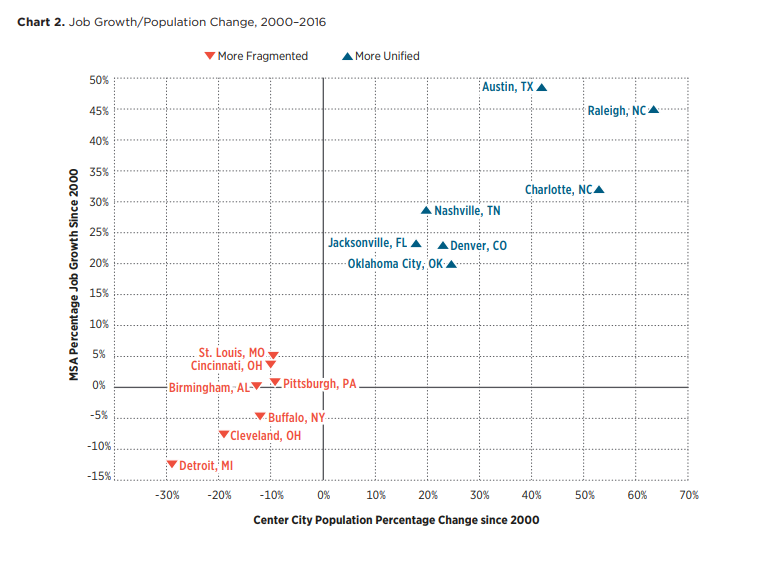

Published in June 2017, Together We Can concluded that Birmingham and other similarly fragmented cities consistently performed more poorly on economic and social measures than more unified metros. Cities around the country have long worked to overcome the challenges presented by fragmentation, and the report described four organizational models used by cities to counter fragmentation and increase cooperation.

After releasing the report, the Community Foundation and representatives of the strategic advisory group hand delivered copies to community leaders, spoke to civic clubs, and participated in radio and newspaper interviews and panel discussions. Neither the report nor the CFGB argued for a particular approach to increase cooperation. Nor was the cooperation conversation centered around a particular project or issue. It instead described approaches other cities took and encouraged Birmingham citizens and leaders to find a response that fit local circumstances.

“The education piece was essential,” Nanni said

That neutral approach was important because the prevailing climate among elected officials in Greater Birmingham was suspicion. That was clear during an early presentation to the Jefferson County Mayor’s Association.

“The first time we presented to them there was a lot of tension in the room, particularly among the incumbent mayors. For so long, the atmosphere was one of suspicion and competition. Zero trust. But as they came to see we weren’t trying to force them into something, they started warming up,” Nanni said.

The publication of the report preceded an election cycle in which several mayors’ races were on the ballot. Regional cooperation became an issue talked about in mayoral and council races that took place across the metro in 2017.

And it just so happened that among the new crop of mayors, there were several new faces who were open to new ways of doing things.

You Don’t Have to Reinvent the Wheel

When attempting to break old negative patterns, it is tempting to propose starting from scratch, inventing a new organization or governmental authority to shape a new reality.

However, it’s sometimes best to put existing institutions to work solving problems rather than inventing a new one. In Jefferson County’s case, Together We Prosper proponents looked for an existing cooperative structure that could be repurposed, energized, or motivated to drive cooperation.

The Jefferson County Mayors’ Association emerged as a candidate. It had some legal standing and functionality, but, in the opinion of many of the participating mayors, it wasn’t living up to its full potential. The mayors had a monthly meeting that was paid for by a rotating cast of lobbying groups who got an audience with the mayors in exchange for paying for their lunch. Mayors got to network and casually discuss common experiences, but there was no push to collaborate, innovate, or address common problems.

Let it be their idea

The Community Foundation encouraged and sponsored a half-day summit for the Association, during which it was hoped that the mayors could find an issue they could rally around addressing.

The Community Foundation provided a facilitator to get the conversation going, but the mayors chose the topics to explore.

So it was the mayors themselves who coalesced around a challenging initiative: ending the bidding wars for local businesses. And since they chose it, they felt ownership of the initiative.

Identify Mutual Self Interest

Local governments across the country are waking up to the fact that offering economic incentives for local business relocation is ultimately a losing proposition.

In 2004, communities in the Metro Denver areas enacted a Code of Ethics designed to end business poaching and promote regional cooperation around economic development. Many others have followed suit. Just this year, Missouri and Kansas found a way to end an incentives arms race that was allowing companies to reap incentives by moving between the Missouri and Kansas portions of Kansas City.

According to research, in at least 75 percent of cases, businesses would have made the same decision to relocate or expand whether or not incentives were offered by governments.

If a business is considering equally appealing sites and they know that in the local market municipalities play the incentives game, the richer offer might make a marginal difference. However, the deal doesn’t produce a net gain for the region. The attracting jurisdiction forgoes taxes that may actually be needed to offset the increased traffic or demand for public safety protection. Granting one business tax incentives arguably gives that incoming business an advantage over existing local businesses.

Identify a Champion

To forge consensus and push the process, the Mayor’s Association needed to identify a champion. They found it in Mountain Brook Mayor Stewart Welch. Welch had only been in office two years. He came out of an investment advising and management business. He wasn’t invested in the prevailing political order of things, and he had credibility when talking about business and economics.

Welch reached out to each mayor and worked toward a proposal. The first part of the pledge was easy. The mayors would pledge not to solicit a local business located in a neighboring municipality to move.

It was harder to ask the mayors to give up their tactical weapon.

Welch kept working to convince his fellow mayors that a widely accepted agreement would short-circuit what seemed to be an increasing problem. Expanding businesses within the region were actually motivated to move across municipal lines, because it was expected that they could get incentives to move or, when those incentives were put on the table, they’d get an incentive offer to stay where they were.

Welch worked to convince mayors that it was a counterproductive and unnecessary exercise to incentivize moves that were going to happen regardless. It was a losing proposition for each city and the region, he argued. It diverted resources, time, and attention that should have been spent on bringing in businesses from outside the region, a business that would result in a net gain in employment and population for the region.

Do your Homework

While the initial report included a description of the Denver area’s no-poaching Code of Ethics, the Community Foundation provided Welch and the other mayors with additional research support. They helped locate five other similar agreements from around the country and arranged phone conferences between mayors and the individuals in Denver who were involved in crafting the no-poaching agreement there. The mayor of Birmingham provided a staff member’s assistance with the drafting process.

Welch began circulating drafts, and with the other mayors’ input, they moved toward mutually agreeable language. And they came up with a catchy name: “The Good Neighbor Pledge.”

Declare Victory

Eventually, 23 cities agreed to sign on, including the eight largest. In sum, the signatories represent about 85 percent of the county population. Even though three sizable suburbs — Irondale, Fultondale, and Gardendale — declined to sign, the “coalition of the willing” moved ahead.

The mayors gathered at the Jefferson County Courthouse to formally sign the agreement with the Jefferson County Commission looking on. The event drew favorable press coverage and continues to inspire further conversation about additional cooperative ventures.

Success Begets Success

The Good Neighbor Pledge is not a legally binding agreement. It doesn’t have “teeth.”

The mayors are still working on a dispute resolution process that could handle conflicts over the Good Neighbor Pledge if they were to occur.

Going forward, the mayors have discussed increased cooperation on 9-1-1 services. They’ve also discussed creating a comprehensive countywide or even regional listing of available office and commercial space and industrial parks.

Regardless of what is next, it is hoped that the mayors have taken a step toward communication and cooperation in a local landscape that has traditionally been marred by distrust and competition. And they continue to look out for self-interested opportunities to help improve conditions for all.