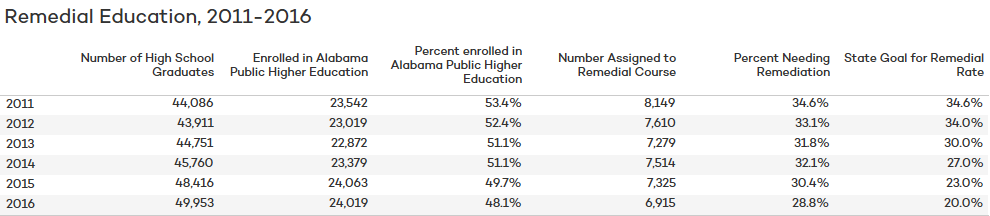

The latest statistics from the Alabama Commission on Higher Education (ACHE) show that Alabama high schools are making progress in producing graduates who are ready for college-level coursework.

According to the new report from ACHE, the percentage of high school graduates who had to take remedial courses upon entering Alabama colleges decreased to 28.8 percent for the graduating class of 2016, down from 30.4 percent in 2015 and 34.6 percent in 2011.

Why is remediation an issue?

In a perfect world, any student graduating from an Alabama high school who wishes to enter college would receive a level of education in high school that would prepare them for college-level courses.

However, that is often not the case. When colleges assess incoming students, the colleges often find that the students are in need of a catch-up course at college before they’re ready to tackle college-level work.

These remedial courses don’t count toward attainment of a college degree. They impose an expense on the students and the colleges, an expense that adds to the time and cost of attaining a college degree.

Alabama’s strategic plan for improving K-12 education, Plan 2020, set a goal of decreasing the remediation rate. When high schools do a better job of preparing students for college-level work, it produces savings for the student, their parents, and the education system in general.

While the goal set in Plan 2020 to reduce the remediation rate by approximately 3 percent a year has not been attained, K-12 schools have made progress.

To explore the statics for remediation and college going for local systems, follow this link. Bear in mind that the ACHE report only captures high school graduates who enrolled in the fall after their graduation in Alabama public colleges. The college-going and remediation rates for schools that send significant numbers of students to private colleges or to out-of-state colleges will not necessarily reflect the outcomes for the entire graduating class.

Progress Being Made

According to the ACHE data, the number of high school graduates in Alabama increased from 44,086 in 2011 to 49,953 in 2016, as the population has grown, and the graduation rate has improved.

The number of high school students enrolling at in-state public colleges has increased as well, though in 2016 the total enrollment number was down slightly in comparison to 2015.

However, the percentage of high school graduates enrolling in Alabama public colleges in the fall after graduation has declined slightly. In 2016, 48 percent of high school graduates enrolled in Alabama higher education the following fall, compared to 53.4 percent in 2011. Data from other sources indicates that the total post-high school college-going rate for Alabama is around 62 percent (Unlike this set of ACHE statistics, those statistics capture students who go to private colleges or who go to college out-of-state).

In 2016, about half of the enrollees went to a two-year college and the other half to four-year colleges.

Remediation rates are calculated for two subjects: math and English.

The most progress has been made in decreasing the percentage of students having to take remedial English. In 2016, the percentage of students needing remedial courses in English dropped to 13 percent, down from 17 percent in 2013.

The percentage of enrolled students taking remedial math also declined to 24 percent in 2016, compared to 26 percent in 2013.

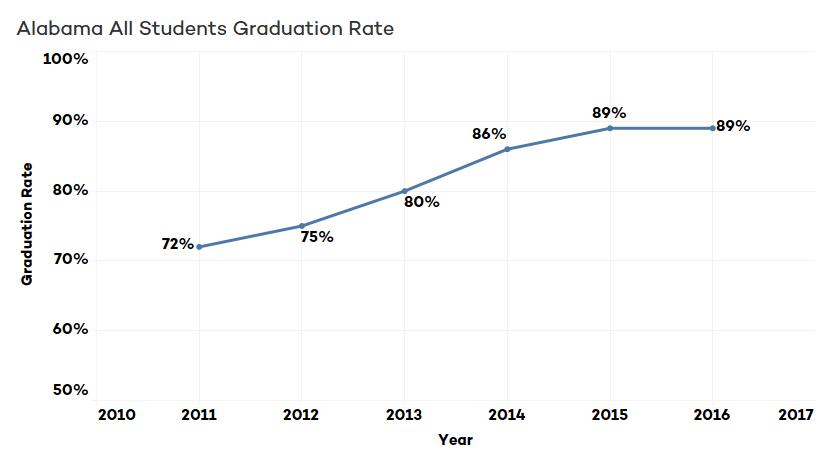

High School Graduation Rates

Remedial rates and college-going rates are affected by changes in Alabama’s high school graduation rate. At the same time that the remediation rate has gone down, Alabama high schools have improved the high school graduation rate. In 2011, only 72 percent of students in Alabama high schools graduated on time. In 2016, the most recent year available, 89 percent of students graduated on time according to Alabama’s definition of graduation. To see PARCA’s presentation of 2016 high school graduation rates for the state and local schools, follow this link.

The rapid rise in Alabama’s graduation rate has sparked some concern about whether Alabama’s rate had become inflated, that Alabama schools had lowered their standards for awarding high school diplomas. In trying to improve graduation rates, the state and local schools had made several changes. Alabama instituted a credit recovery system that allowed students who had failed the class to take targeted instruction to improve their areas of weakness rather than having them repeat the entire course. Alabama also dropped its high school exit exam, which had, in the past, prevented some students from graduating. Finally, the state also changed the way it defined who was eligible to receive a diploma and began allowing special education students taking “Essentials” courses (courses not fully aligned with Alabama academic standards) to count those courses toward graduation.

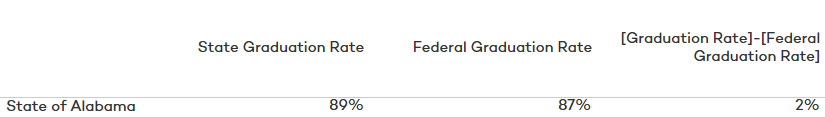

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Education launched an inquiry into Alabama’s standards for granting high school diplomas. As a result of the investigation and an audit of records, some of the students who took the Essentials classes should not have been counted as graduates under the federal definition of a graduate. After a thorough audit of student records, the 2016 graduation was recalculated removing some of those students in the Essentials pathways from the total counted as graduates. In the end, the graduation rate re-calculated for federal reporting was two percentage points lower than Alabama’s definition of who is a graduate.

The 2016 graduation rate report now includes both a state graduation rate and a federal graduation rate. The most significant difference between the two rates is found among special education students. According to Alabama’s definition, 72 percent of special education students were counted as high school graduates in 2016. Under the federal definition which excludes the Essentials courses, only 54 percent of special education students were counted as graduates. That’s 1,106 fewer special education students counted as graduates under the federal definition.

Despite the concerns about the graduation rate, the new improved, lower remediation rate reported in the ACHE reports provides evidence that Alabama high schools are providing higher levels of preparation for graduates headed into higher education. However, the decline in the college-going rate also bears watching. The lower Alabama public college-going rate may indicate that some students are going straight into the workforce thanks to improvements in the economy. It may also indicate some graduates don’t feel adequately prepared to immediately enter college. The cost of college has also continued to rise which may discourage some high school graduates from entering college.

Where do we go from here?

Alabama high schools should continue to increase the quality of education delivered in high school so that students enter college prepared for college-level work. High schools and colleges should also continue to improve efforts to help students apply for and finance a college education. According to the latest available statistics from the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS), Alabama’s rate for college going immediately after high school is 62.1 percent, slightly behind the national average of 62.6 percent. However, Alabama’s rate is lower than any other Southeastern state, indicating room for improvement.