PARCA’s latest report, commissioned by the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham, focuses on the fragmentation of the Birmingham region, the challenges it causes, and potential solutions exemplified by other metro areas around the country.

With the clouds of Jefferson County’s bankruptcy lifting and downtown Birmingham showing impressive signs of revival, optimism about the region’s future is high.

Considering the positive signs, it’s important to ask whether the community is prepared and positioned to capitalize on its current momentum.

In recent decades, Birmingham and its metro area have underperformed in job and population growth in comparison to comparable cities. That begs the question: Why?

Nationally, a substantial body of research indicates that metro areas with more broad-based, cooperative governmental arrangements grow faster and generate greater prosperity than metro areas that are governmentally fragmented, divided into a multitude of independent municipalities.

The region’s central city of Birmingham is surrounded by more independent suburbs than any other southern city. This pattern of fragmentation has consequences. It leads to duplication, creates intra-regional competition, concentrates economic advantage and disadvantage, and diffuses resources and leadership. It makes it difficult to arrive at consensus, pursue priorities of regional importance, or deliver services that transcend municipal boundaries. In sum, it puts the metro area at a disadvantage.

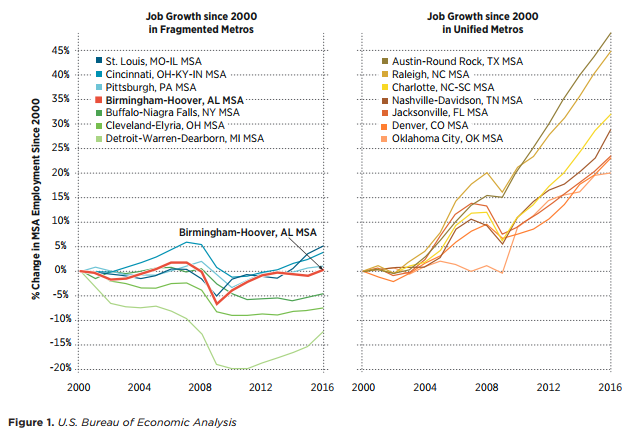

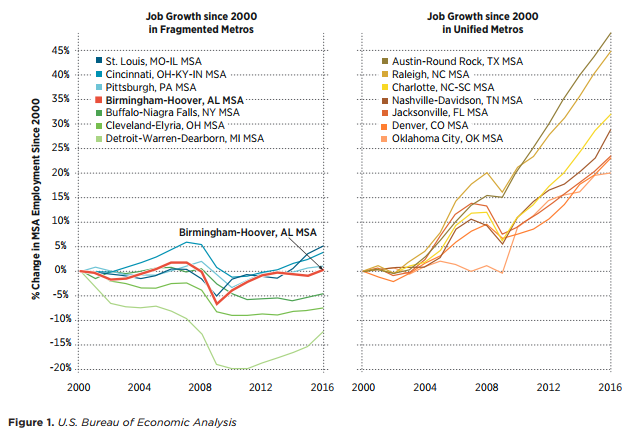

Figure 1 compares job growth since 2000 in two groups of metropolitan areas. The seven cities on the left are fragmented like Birmingham: a diminished central city ringed by a multitude of suburbs.

The seven metros on the right have governmental structures that unite the region. In the more unified metros, job growth since 2000 ranges from 20 percent to 50 percent. In the fragmented metros, job growth ranges from 5 percent to -12 percent.

—

Average annual employment in Birmingham-Hoover MSA has increased by only 0.24 percent since 2000.

The same contrast emerges when comparing median income and poverty and unemployment rates: In cities where government is fragmented, growth is slower, and social and economic problems are more concentrated.

The negative effects of fragmentation weigh not only on the center city but also on the metropolitan area as a whole. The fortunes of the central city and its suburbs are interlocked.

Fragmentation is a long-term process, a deeply ingrained pattern of development that Birmingham shares with northern cities that have a similar industrial heritage. It is not easily undone. In no instance in the post-World War II era has there been a mass political consolidation that dissolved existing cities or school districts. However, cities across the country have developed alternative approaches that promote unity and increase cooperation within their metro areas.

In 2016, the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham commissioned the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama (PARCA) to conduct a study of the current structure of government in Greater Birmingham, with Jefferson County as its primary focus. The study was to examine Greater Birmingham’s historic development and its current state in comparison with other cities, to describe different options other cities have pursued to overcome fragmentation, and finally, to explore how those different options might work in the Birmingham context.

This resulting report was developed with advice and review from a Strategic Advisory Group convened by the Community Foundation. Members of the Strategic Advisory Group were selected to provide a range of perspectives representing the larger Jefferson County community.

Locally, a wide range of public officials from the central city, the suburbs, and the county were also consulted, as were leaders in business and civic groups.

KEY FINDINGS

Fragmentation has led to a decline in Birmingham’s prominence and its ability to lead the region.

In 1950, Birmingham was the 34th largest city in the U.S. According to the latest population estimates, the city has fallen out of the top 100. Though the latest estimates indicate the city may have halted its population decline, other Alabama cities where growth is strong may eventually displace Birmingham as Alabama’s largest city.

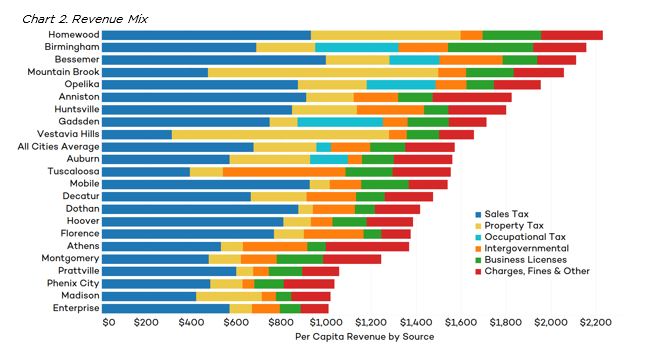

The population of the City of Birmingham now represents only 32 percent of Jefferson County’s population compared to 60 percent in 1950. The city still holds a position of regional leadership thanks to its ability to draw taxes from businesses and commuters who come into the city to work or shop. Over 90,000 people commute into the city each day, filling more than half of the jobs in the city. According to PARCA’s analysis, city residents contribute 33 percent of city taxes, non-residents contribute 28 percent, and businesses 39 percent.

However, Birmingham’s role as chief supporter of regional assets and projects is under increasing strain, as it struggles to meet not only that role but also the needs of economically distressed neighborhoods and residents.

Fragmentation is a drag on metropolitan growth.

The Birmingham-Hoover MSA is currently the 49th largest in the U.S., but its growth in employment and population is slow compared to peer MSAs. Growth is particularly lagging in its central county, Jefferson. Recent projections estimate Jefferson County will add only 8,967 new residents by 2040, a 1.4 percent increase over the current population.

Greater Birmingham has not developed a viable alternative for regional leadership.

While Jefferson County has positioned itself to better play a regional leadership role thanks to recent improvements in its finances and management, it still lacks an executive branch. Nearly half of the large counties in the U.S. are now headed by an elected CEO, creating a strong and capable executive branch charged with the management of the county government. Jefferson County is still governed by a five-member commission elected by district. Additionally, the 26-member Jefferson County Legislative Delegation exercises substantial control over local affairs.

Greater Birmingham needs a spirit of governmental innovation.

Across the country, local governments are innovating with form and function, finding new ways to collaborate, economize, and deliver better customer service. Greater Birmingham need not be bound to traditional ways of doing things.

INSIGHTS FROM OTHER CITIES

PARCA’s research identified four different approaches cities and metro areas take toward building and maintaining regional unity. Four cities representing the four different approaches were selected for study.

The four approaches are:

1. Functional Consolidation

Decreasing duplication and increasing efficiency through cooperative agreements between local governments.

Example Metro: Charlotte, North Carolina

2. Modernizing County Government

Structuring county government to provide regional leadership.

Example Metro: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

3. Cooperation Through Regional Entities

Using regional bodies to deliver services or coordinate strategy on a region-wide basis. These can be public or private, or a fusion of the two.

Example Metro: Denver, Colorado

4. Political Consolidation

Most often, the merger of the central city with the central county, creating an umbrella metro government to deliver regional level services.

Example Metro: Louisville, Kentucky

Once labeled “the most segregated city in America,” Birmingham is justly proud of its historic role in breaking down the walls of segregation that once legally separated blacks and whites.

The time is now right to re-examine the barriers to unity that were created in the past and develop a new approach that better meets the needs of all the people in the Birmingham metropolitan area—urban, suburban, and rural. No one approach rules out the others. In crafting an approach that meets its unique needs, Birmingham might borrow ideas from each.

This is not a new issue for the region, and greater Birmingham is not alone in having tried multiple times to resolve it.

Louisville and Nashville each failed twice before achieving governmental consolidation, and Charlotte created its intergovernmental cooperation strategy as an alternative to unachievable structural change. Pittsburgh took a first step to attack fragmentation by reforming county government, just as Denver did by creating special-purpose regional authorities with their own tax sources.

The question of community unity has been a recurring strain in Birmingham’s history. Greater Birmingham was catapulted to the status of major American city through a consolidation in the first decade of the 20th Century. Multiple votes from the 1940s through the 1960s presented city-suburban merger as an option but failed to garner adequate support. A different approach, the Metropolitan Area Project Strategies, was proposed in the late 1990s.

With the negative effects of fragmentation having become very clear, it is time for fresh ideas and new conversation about how Greater Birmingham can chart a new, more prosperous course. The public seems ready to engage in this conversation.

View the full report here and access additional components of the project here.