Despite the pandemic, Alabama public schools maintained a high on-time graduation rate in 2020. However, the number and percentage of students meeting the state’s definition of college and career-ready fell by 4 percentage points, likely held back by missed opportunities due to the closure of schools in March 2020.

Because of the challenges posed by the pandemic, state policy allowed seniors to graduate as long as they were in good standing at the end of the third nine weeks of the 2020 school year (local systems made the final decision over who qualified for graduation). For this cohort of seniors, students who were 9th graders in 2017, 92% received a diploma in 2020.

However, when it came to college and career readiness measures, some of those seniors were unable to complete the requirements, as the final months of the 2020 school year were conducted online. Of that same cohort, 76% met the definition of college and career-ready established by the Alabama State Board of Education.

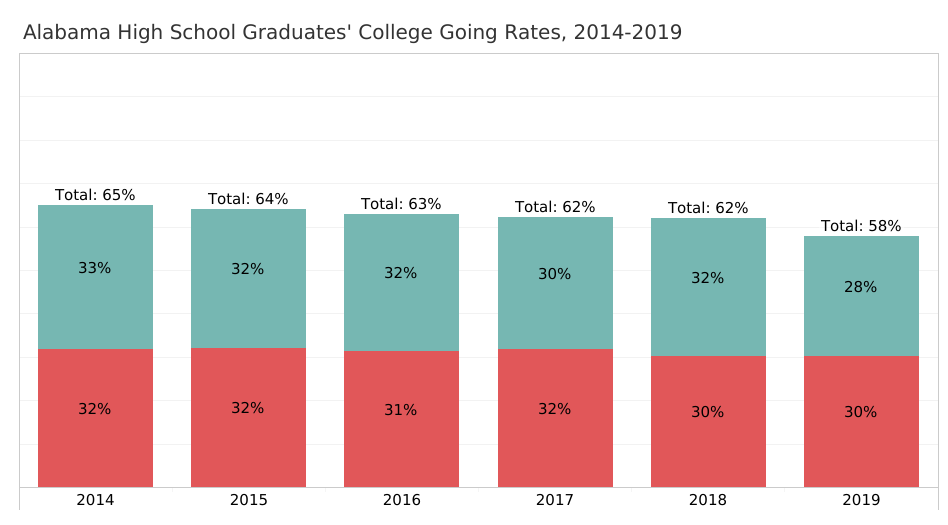

Other data suggest that fewer of those 2020 graduates enrolled in higher education after graduation. The Alabama Commission on Higher Education has reported a 10% decline in the number of Alabama high school graduates enrolling in higher education in the fall of 2020 compared to the previous year, with community college enrollment most affected. The enrollment decline had more to do with the unprecedented circumstances of the pandemic than the decline in the college and career readiness rate (CCR rate).

Still, the CCR rate and the decline in higher education enrollment should be noted as the state seeks to make up for lost time and opportunity in the aftermath of the pandemic. Alabama’s 2020 high school graduation rate will likely be among the nation’s highest again. In 2019, Alabama’s reported federal graduation rate, 91.7%, was the highest in the nation. It was the culmination of a steep rise — Alabama’s graduation rate was 72% in 2011. Historically, the state’s graduation rate has been in the lower tier of states.

Despite the meteoric rise in the graduation rate, the CCR rate and other measures indicate that Alabama schools still have work to do when it comes to turning out prepared graduates. The State Department of Education has called on public schools and systems to close the gap between the graduation rate and the CCR rate. Ideally, every student should graduate ready to succeed in college or in advanced training that leads to higher-paying jobs. The CCR rate can also indicate the range of education and training opportunities available to students at a school or in a system and in normal conditions, serves as a gauge of the effectiveness of the educational program offered.

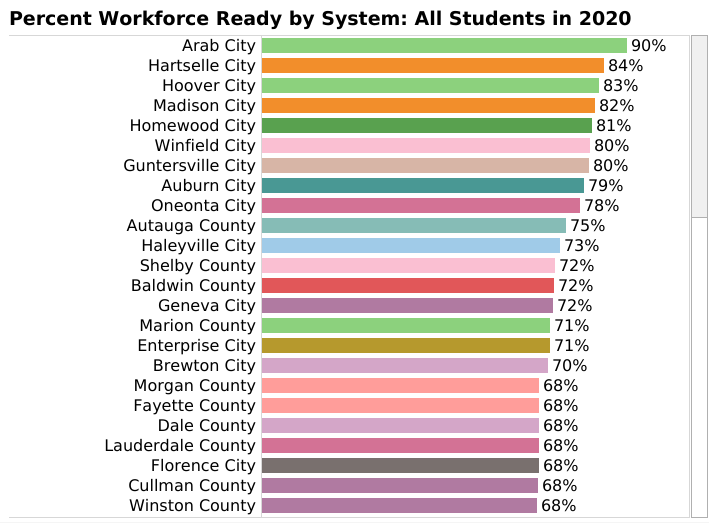

Gaps between school systems

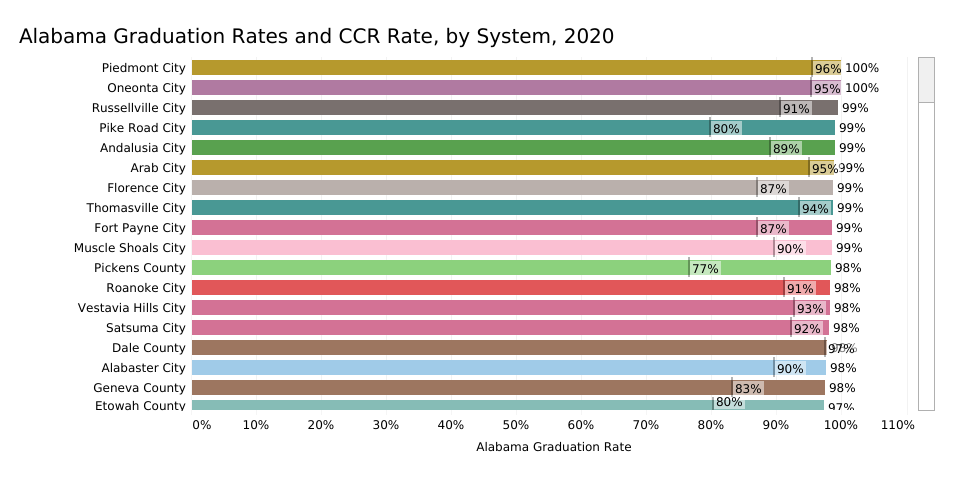

When looking at local school systems, wide gaps remain even in the graduation rate. While 100% of students graduated from Piedmont and Oneota City Schools in 2020, only 69% of Bessemer seniors graduated on time.

The gaps are wide in college and career readiness as well. In 2020, 97% of Dale County seniors were rated as college or career ready, compared to only 25% of Bessemer seniors.

Gaps between student subgroups

Alabama’s graduation rate gap between the races and socio-economic groups has also narrowed at the state level. But when it comes to college and career readiness, gaps between the races and between socio-economic groups persist. For example, 84% of white seniors are rated college and career ready, while only 64% of Black seniors earn the distinction.

Does the CCR rate really matter?

To be counted as college and career ready, an Alabama high school student must meet at least one of six different indicators. In an official sense, a student’s status as college and career-ready doesn’t matter. It is not required for graduation. Neither colleges nor employers look for the rating on an individual’s resume.

On the other hand, some of the indicators have real-world implications for individuals. They can help an individual get into college, secure college credit, or successfully apply for a job. The chart below shows the percentage of seniors earning the college and career readiness distinction through each of the established measures. A detailed description of each of the measures follows the chart.

The changes in the percentage of students earning college and career readiness in each of the categories reflect changes in emphasis, investment, and effort. The changes can also reflect strategic choices by students or schools to pursue the easiest path for meeting college and career readiness requirements.

Below are the indicators of college and career readiness as established by the State Board of Education.

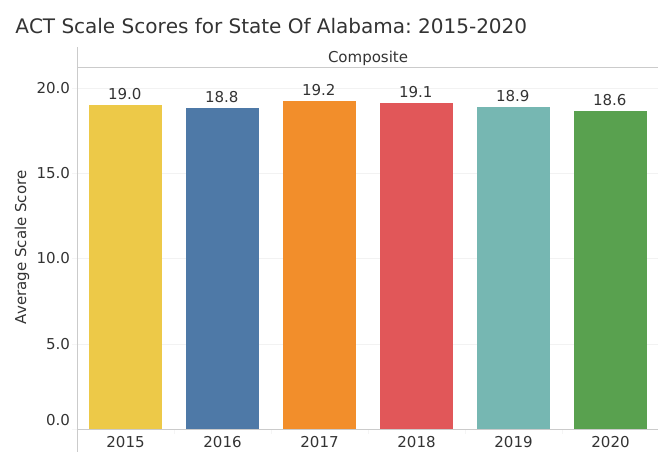

1. Score at or above the benchmark on one section of the ACT, the college-readiness test

In recent years, about 50% of students benchmarked on the ACT in at least one subject, most commonly English. According to ACT, a student who scores at or above the benchmark in a subject has a 50% chance of making a B in a college course in that same subject.

For the Class of 2020, only 46% of students made at least one benchmark score. With the coming of the pandemic, ACT had to cancel several test dates, which may have prevented some students from retaking the test and reaching the benchmark score. In light of that, many colleges and universities waived the ACT requirement for admission.

Still, the ACT results might also indicate that the disruption left some seniors less prepared for college.

2. Score Workforce Ready on the ACT WorkKeys test

In addition to its academically oriented college-readiness test, ACT offers WorkKeys, a standardized test that measures practical skills in math, language, and comprehension, skills as they might be applied in the workplace.

In 2019, 61% of seniors scored Silver or above on the WorkKeys, an indicator that they had the practical skills needed to function in most workplaces.

For the class of 2020, only 45% of seniors earned scored Silver or above. One potential reason for the drop is that schools are no longer required to give WorkKeys to every senior. Many systems, particularly those with an orientation toward college preparation, let students who scored college-ready on the ACT skip the WorkKeys test.

Also, for the Class of 2020, the WorkKeys was given in the Fall of 2019 as usual. But normally, spring re-tests offer opportunities for students to improve their scores. These re-tests were canceled in 2020 due to the pandemic.

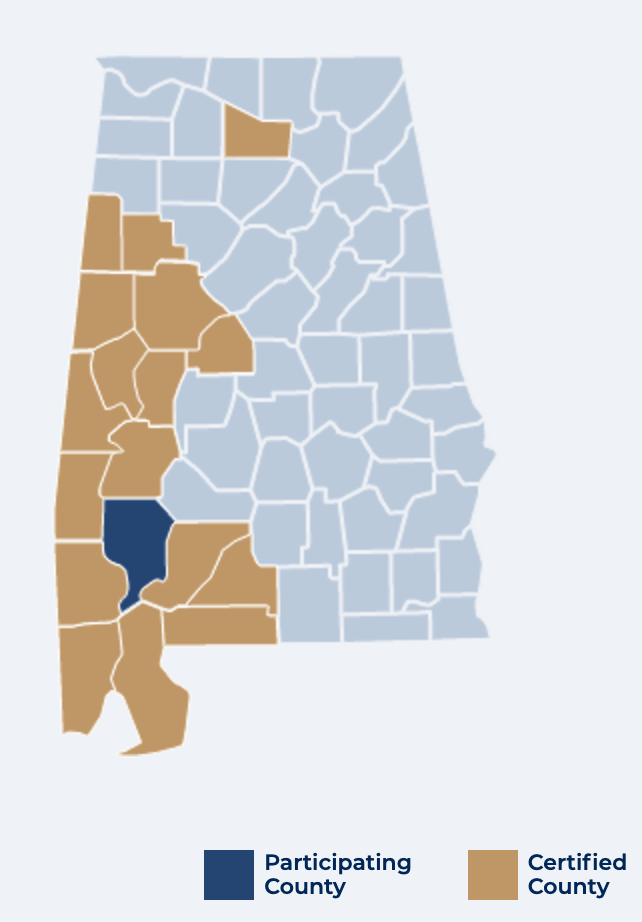

For some, that lack of opportunity to better their WorkKeys scores has implications. Employers in some regions of the state, particularly West Alabama, have come to value the WorkKeys results as a meaningful credential. But there is a remedy. For those graduates who want the credential, Alabama’s two-year colleges offer preparation and WorkKeys testing.

3. Score 3 or above on an Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) end-of-course test

AP and IB are college-level courses offered in high schools led by a trained teacher, following a nationally standard curriculum. Scoring 3 or above (out of 5) on an end-of-course test can earn a student college credit in the corresponding college course. IB exams were canceled in 2020 because of the pandemic. However, AP tests proceeded in an online format. Impressively, the percentage of seniors earning AP credit (11%) was only down 1 percentage point from the previous year.

4. Earn an industry-recognized credential through a Career Technical Education course

In 2020, 35% of seniors graduated having earned at least one industry-recognized credential. Considering that many of the credential certification tests don’t take place until the end of the year, it is impressive that the percentage of seniors earning a credential was only down two percentage points, from 37% in 2019.

Overall, the number of credentials earned in 2020 was down significantly compared to 2019 (final tallies are still being compiled). However, seniors appeared to have already earned credentials in prior years or earlier in the school year. The change to online instruction after March of 2020 disrupted the normal process of awarding credentials and closed some avenues for earning them. However, schools were encouraged to make a special effort to help seniors complete their industry-recognized credentials, an effort that appears to have been largely successful.

5. Earn college credit through dual enrollment

This is the one area that actually saw an increase, with 15% of graduating seniors earning college credit through dual enrollment in 2020 compared to 14% the year prior.

Dual enrollment, having high school students take classes for credit through universities or community colleges, has been gradually increasing in participation. Apparently, the courses were able to continue and be completed virtually.

6. Successfully enlist in the military

In 2020, 2% of graduating seniors enlisted in the military, a percentage that has been consistent for several years.

One notes trends in looking across the years at the variety of methods for achieving college and career readiness. The percentage of students CCR Ready on the ACT has been relatively flat. The percentage CCR Ready through WorkKeys has grown as schools and students have become more familiar with the test, though it fell back in 2020 thanks to changes in policy and disruptions. An increasing number and percentage of students have demonstrated college and career readiness through success in AP courses, dual enrollment, and in particular, participation in career technical education.

Different approaches to achieving college and career readiness

While a statewide analysis of college and career readiness measures provides some insight, a closer examination of local system results reveals that there is a tremendous variety in how different school systems approach college and career readiness for their students. For example, magnet schools and affluent suburban systems record high percentages of students earning benchmark scores on the ACT or AP. Systems with a close relationship with a local community college might offer more dual enrollment opportunities. At the same time, schools with strong career technical education programs might produce more college and career-ready students through that route.

Conclusion

The Covid-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges for schools and students. Schools and students posted relatively minor and understandable declines on major performance measures like the high school graduation rate and the college and career ready rate.

However, at a time when the state has set lofty goals for raising the educational attainment level of the workforce, both the pandemic and underlying trends point to needed areas of focus.

Alabama’s high school graduation rate is high. Still, students need to graduate better prepared with meaningful credentials and solid evidence that they are ready for education and training beyond high school. In 2020, 24% of high school seniors failed to demonstrate college and career readiness, even by the relatively generous standards established by the Alabama State Board of Education.

Among Alabama high school graduates, an increasing number are not seeking higher education. Some of that may stem from a robust job market that is drawing graduates straight into the workforce. Some of the most recent drop is pandemic related. However, for individuals’ long-term prosperity and for the state’s economic future, our workforce needs increasing levels of education and training. There needs to be continued attention to building solid bridges between high school and the next level of opportunity. There is also an opportunity to reach out to recent graduates, particularly 2020 graduates affected by the pandemic, to make sure they have access to advanced education and training.