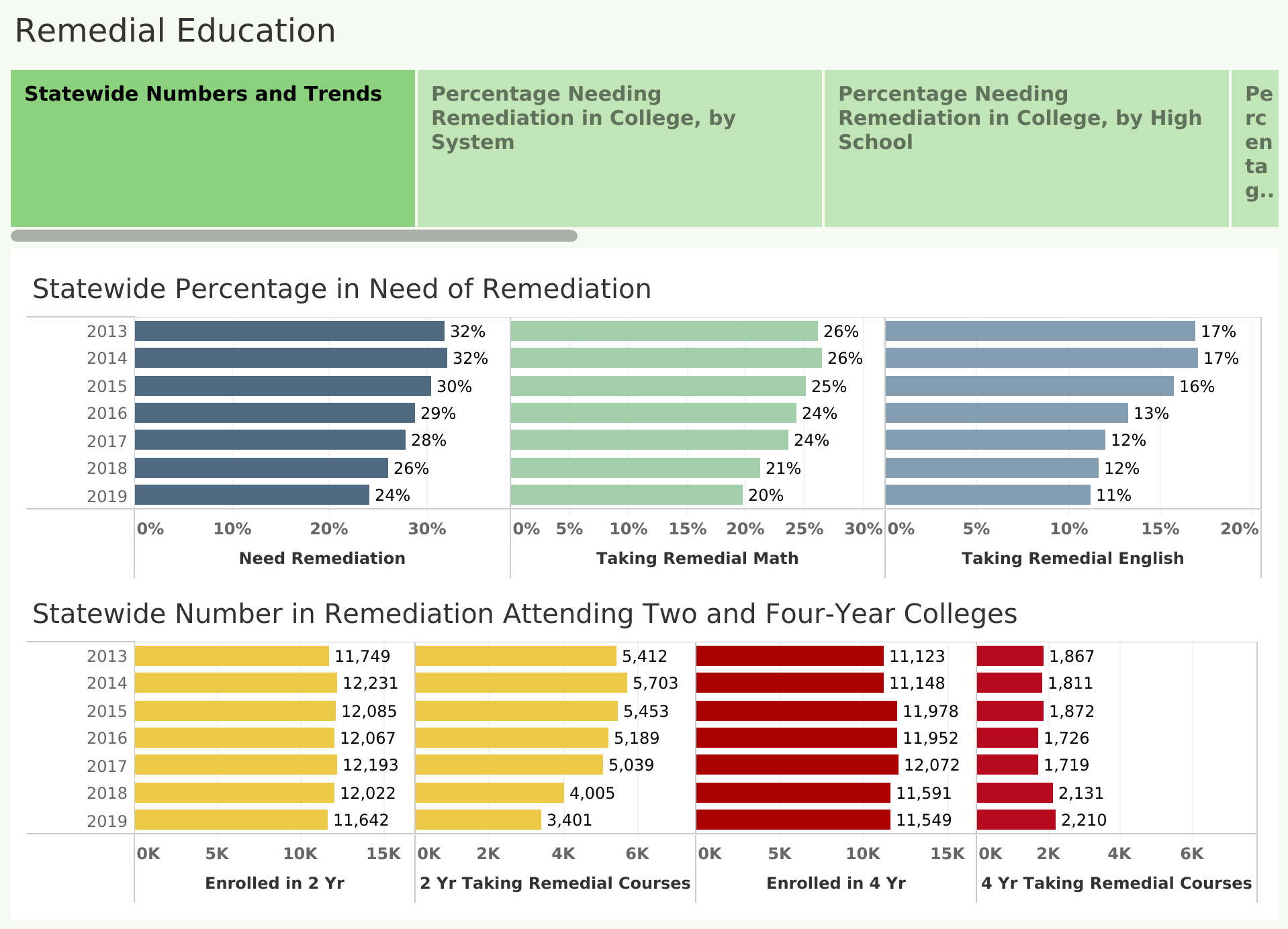

The number and percentage of Alabama public high school graduates assigned to remedial courses upon entering college continued to decline in 2019, one measure of academic progress for K-12 schools and Alabama’s public higher education system.

Remedial classes are non-credit college courses covering material students should have learned in high school. Alabama’s Community College System (ACCS) has recently developed alternatives to those courses, and the decline is attributable to those schools. According to ACCS, not only are fewer students being placed in remedial courses, but also passage rates in introductory courses have risen. Meanwhile, the number of students assigned to remedial courses at four-year colleges has increased modestly.

The data comes from the Alabama Commission on Higher Education (ACHE), the state higher education coordinating board. ACHE works with K-12 and colleges to follow the progression of Alabama high school graduates into Alabama public colleges.

The data provides feedback to high schools about how prepared their graduates are and can give colleges insight for improving student success. Use the tabs in the visualization to explore the data. Compare the performance of graduates from your local high school or system.

This remediation data is the final dataset that looks back on students who graduated in the Spring of 2019. For that school year, PARCA previously published analyses of standardized tests, performance on ACT and WorkKeys, graduation and college and career readiness, and on college-going.

Progress Toward an Educational Goal

Decreasing the number of Alabama public high school graduates needing remediation in college was a goal identified in Alabama’s strategic plan for education, Plan 2020, adopted in 2012.

Remedial education is considered a waste of money for both the state and the individuals paying for higher education. Remedial courses cover material that should be covered in high school. Remedial classes cost students tuition and fees but do not produce credits that count toward graduation. By avoiding remedial courses, students are able to complete college work in a more timely fashion and at less cost.

A combination of factors have likely driven the decline in remediation. Factors include:

- Policy changes at two-year colleges that prescribe tutoring alongside introductory college classes, rather than assignment to a remedial class.

- Better preparation of students in K-12.

- Changes in college-going rates due to the high job availability.

The declines have been equal in reading and math. In 2013, 26% of students required remedial math, and 17% required remedial English. With the class of 2019, only 20% required remedial math, and 11% required remedial English.

Community Colleges Providing Alternatives

In 2018, The Alabama Community College System (ACCS) made system-wide changes designed intentionally to reduce the number of students enrolled in developmental or remedial courses. Students were still assessed for their levels of academic preparation upon enrollment, but, instead of being assigned to either regular or remedial courses, the system used a new tiered placement model. One innovation was enrolling students who needed extra support in a corequisite/tutorial course alongside college-level Math or English. Since the change, the number of students in remedial classes has declined, but the percentage of students passing gateway English and math has increased.

Loading…

Loading…

Are entering college students better prepared?

Since 2012, Alabama has pursued multiple strategies to improve K-12 education and to produce high school graduates who are better prepared for college and career.

Most directly tied to college preparation, the state has increased support for dual enrollment, which allows high school students to take courses at colleges, and for Advanced Placement courses, college-level courses taught by high school faculty members. Thanks to additional funding, the number of Advanced Placement Courses offered has increased. Much of that expansion has been in schools with higher numbers of economically disadvantaged students. The success rate on AP tests remained constant between 2013 and 2019, indicating that the expansion was maintaining quality while expanding opportunity.

Despite those efforts, scores for Alabama high school graduates on the ACT, the college-readiness test given to all students, have been flat to slightly declining. And while the number of students assigned to remediation has decreased in the two-year system, as noted, the number of remedial students has risen at four-year colleges.

Are a different mix of students attending college?

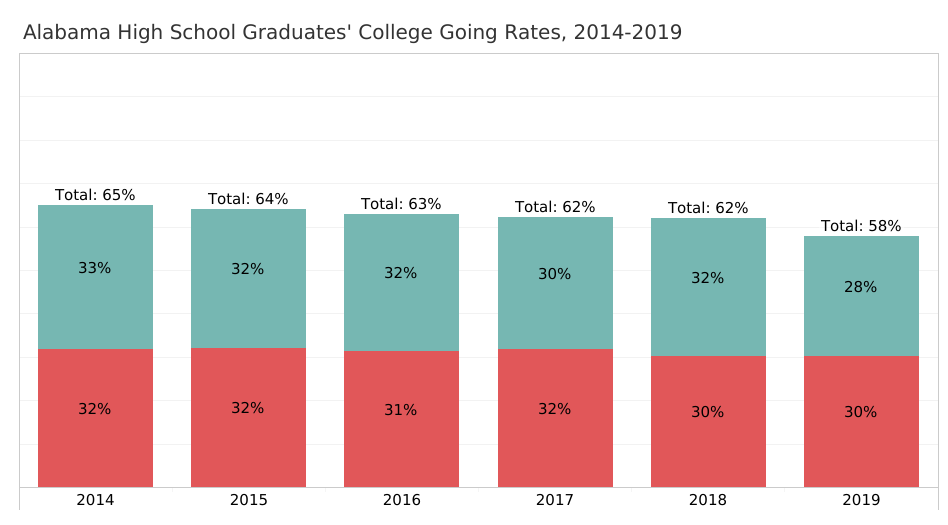

Another factor that may be affecting the remediation rate is the choices high school graduates are making about college. Since 2014, the percentage of high school graduates going directly to college has declined from 65% to 58% in 2019. (See PARCA’s analysis of college-going trends). Over that period, Alabama’s high school graduation rate and the number of graduates produced has increased. Most of the enrollment decline has been in the two-year system. Community colleges tend to see enrollment declines when the economy is growing, and the demand for workers is high. In the fall of 2019, when Alabama’s unemployment rate was at a historic low, enrollment in the community college system dipped below 80,000, down from over 90,000 earlier in the decade as the state was emerging from the Great Recession.

It may be that a greater share of the high school graduates who would have needed remediation in college have instead gone straight into the workforce.

Conclusion

Remediation is needed for students enrolling with a major gap in their readiness for college. Given the open admissions policy in the two-year system and for some four-year colleges, remedial courses continue to play a role in higher education. For others who need some help rising to the level of college coursework, it benefits students and schools to provide alternatives to remediation. The most straightforward solution is to improve preparation in high school, and those efforts should continue. The two-year system’s strategy to provide simultaneous tutoring rather than sequential remedial courses appears to benefit students, increasing passing and progression rates. The model ACCS has developed should also be explored for replication at four-year colleges.