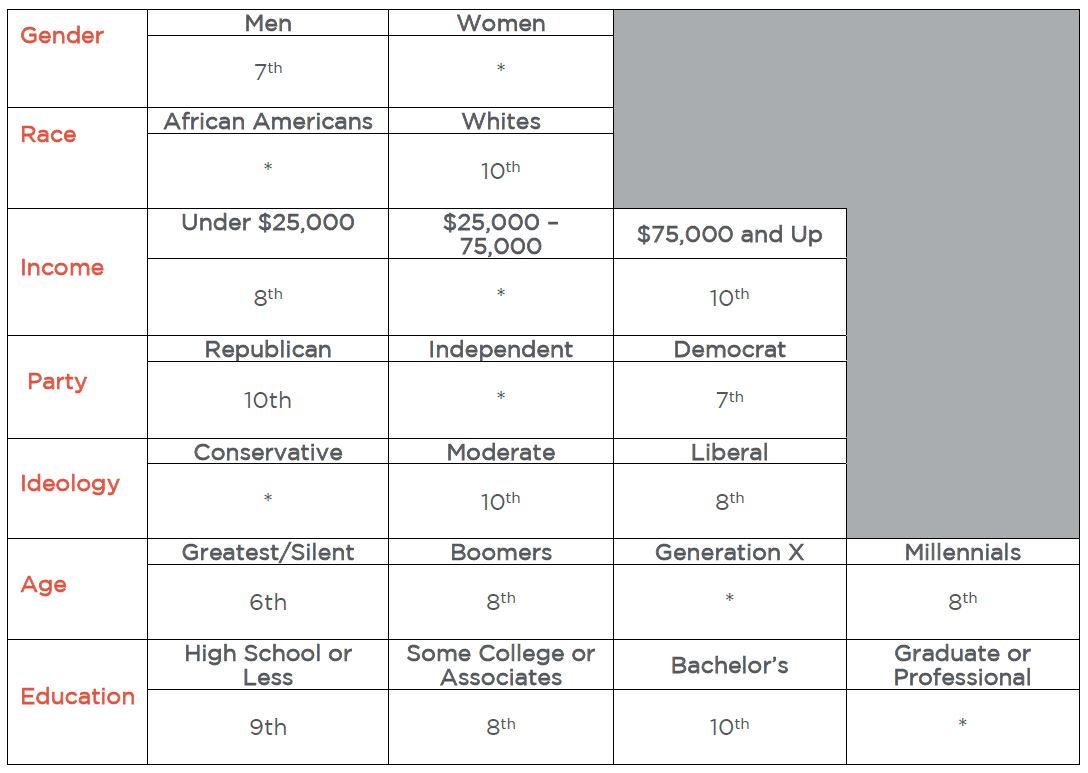

In late 2017, the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama (PARCA) surveyed Alabama voters to determine their thoughts about the general direction of the state and the issues that most concern them. PARCA partnered with Samford University to survey policy professionals from across the state including academics, journalists, business and nonprofit leaders, and lobbyists. Their responses provided a list of 17 critical issues facing Alabama. PARCA partnered with USA Polling at the University of South Alabama to ask registered voters about these 17 issues. The voters’ responses generated the Top Ten list of voter priorities. Details about the survey and its methodology can be found in the full Alabama Priorities report.

Alabama Priorities

| 1. K-12 Education |

| 2. Healthcare |

| 3. Government Corruption and Ethics |

| 4. Mental Health and Substance Abuse |

| 5. Poverty and Homelessness |

| 6. Jobs and the Economy |

| 7. Crime and Public Safety |

| 8. Job Training and Workforce Development |

| 9. Improving the State's Image |

| 10. Tax Reform |

Key Findings

- Voters broadly agree on the critical issues facing the state.

- Voters are not polarized along traditional political, ideological, racial, or generational lines. There is a significant gap between the priorities of experts and the priorities of voters.

- Policymakers have an opportunity to inform and educate voters on critical and systemic challenges facing the state.

- Policymakers have an opportunity to respond to immediate, often highly personal issues that concern voters.

- Elected officials and candidates have an opportunity to show leadership and to build broad coalitions to address Alabama’s most pressing challenges.

In the following months, PARCA will produce summary briefs on each of the top ten priorities chosen by Alabama voters. Each brief will answer four critical questions: what is the issue, why it matters, how Alabama compares, and what options are available to Alabama policymakers.

#5: Poverty and Homelessness

What is the issue?

Poverty and homelessness is the 5th most important issue for Alabama voters, with 58% of voters indicating they are very concerned about the issue. Poverty and homelessness averaged 4.192 on 1–5 scale where 1 is “not at all concerned” and 5 is “very concerned.” The majority of every demographic and political group indicated they were very concerned about this issue.

Why are Poverty and Homelessness Important?

The standard measure of poverty is the percentage of people earning less than a specific dollar amount: the federal poverty line. The federal poverty line is adjusted for the number of people in a household and is revised annually. In 2018, the federal poverty line for a family of four is $25,100. Although the percent of the population living in poverty is in decline, over 39 million people were still in poverty in the U.S. in 2017. Poverty often creates a vicious cycle that can last generations. Poverty complicates and is complicated by almost every other challenge facing Alabama and the nation.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines homelessness, in part, as lacking a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence or a primary residence that was not designed for or ordinarily used as a regular sleeping accommodation for people. On a single night in 2017, an estimated 553,742 people were homeless in the United States. Homeless experts and advocates question the appropriateness of the definition and the accuracy of the number, some suggesting the number to be almost double.[1]

Homelessness can:

- create new health problems and exacerbate existing ones;[2]

- increase the chances of entering the criminal justice system and increase the recidivism rate;[3]

- increase substance misuse;[4] and

- have a negative economic impact on the larger community.

How Does Alabama Compare?

Population in Poverty

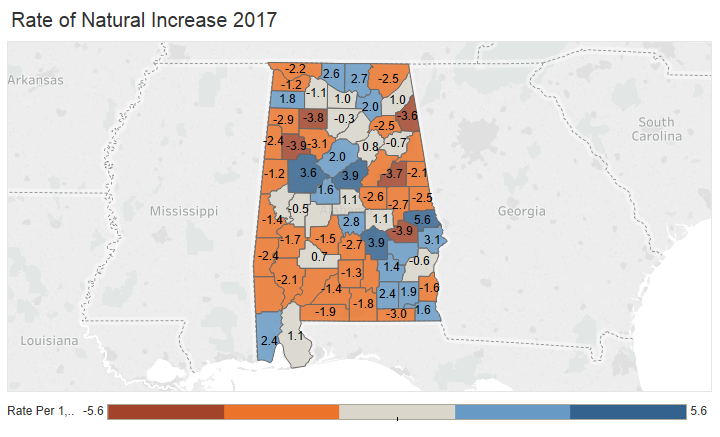

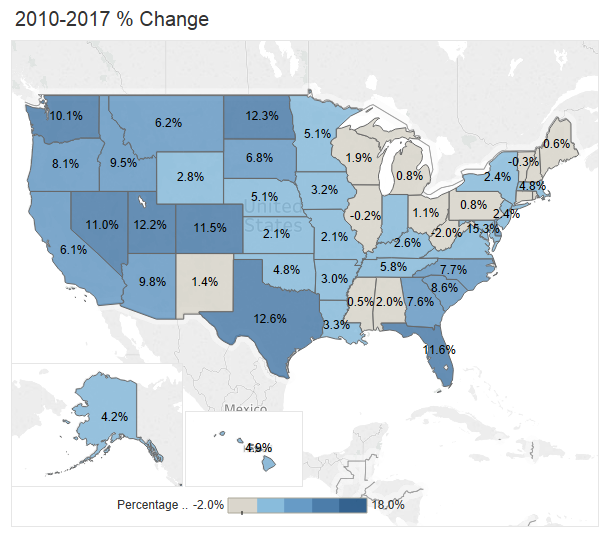

The percent of the population in Alabama living below the federal poverty level has declined from 19% in 2010 to 16.9% in 2017, mirroring declines at the national level. However, the percent of people living below the poverty level in Alabama is still higher than that of the nation. In 2017, Alabama had the 6th highest poverty rate in the U.S. and the fourth highest poverty rate among 10 southeastern states.

Poverty sees no color – while black Alabamians are disproportionately poorer, with 27% living in poverty, white Alabamians are deeply affected as well, with 12% living below the poverty line.[5] Approximately thirty-one percent of Hispanics in Alabama live below the poverty line.

Children in Poverty

Similar to poverty in the total population, the percent of children living in poverty in Alabama is consistently higher than that of the nation. During the period 2010 to 2017, childhood poverty declined for the state, reaching 24.6% in 2017. When compared to southeastern states, the percentage of children in poverty in Alabama ranked higher than all states except Louisiana at 28% and Mississippi at 26.9%.

Homelessness

In 2017, there were an estimated 3,793 homeless people in Alabama, a decrease of 7.7% over the previous year and more than 37% since 2010. In the ten-year period between 2007 and 2017, Alabama’s homeless rate decreased at a faster rate than the national average – a 30% decrease in the state compared to a 14.4% decrease nationally. However, Alabama’s percentage change has been lower than a majority of its southeastern neighbors. Also, while homelessness in Alabama is trending in a positive direction, those still struggling with homelessness are sometimes those facing the most profound challenges, including addictions and mental health issues.

What Can We Do?

There is no single solution to reducing poverty or homelessness. As the causes are varied, complex, and differ from region to region across the state, so too must the responses. Private philanthropy and the faith community can do much to assist individuals and families, but the challenge is too large to be left to the private sector alone. Alabama could consider policy responses and interventions that have demonstrated success around the country, some of which are highlighted below.

- Increased investment in education: in 2016, Alabama was 39th among U.S. states in per student spending.[6]

- Expanded student and family support for students in Pre-K through 12th

- Expanded investment in workforce development for under-employed and unemployed adults.

- Expanded educational opportunities and supportive services for low-income adults.

- Expanded access to primary healthcare, especially in rural parts of Alabama.

- Increase family income for those in poverty through expanded employment (24% of survey respondents indicated the number of available jobs was their top economic priority) or increased wages (32% of respondents said increasing the minimum wage was their top economic priority).

- Implement a statewide housing first model to address homelessness.

[1] National Coalition for the Homeless. “Current State of Homelessness” April 2018 http://www.nationalhomeless.org/

[2] National Health Care For The Homeless Council. “Homelessness & Health: What’s The Connection?”, Fact Sheet, June 2011 https://www.nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Hln_health_factsheet_Jan10.pdf

[3] Volunteers of America, “Homelessness and Prisoner Re-Entry”, https://www.voa.org/homelessness-and-prisoner-reentry

[4] National Coalition for the Homeless, “Substance Abuse and Homelessness” July 2009. http://www.nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/addiction.pdf

[5] Census Bureau’s Population Estimates Program. (2017). 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. [Data file]. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_15_1YR_S1701&prodType=table

[6] “Annual Survey of School System Finances” U.S. Census Bureau https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/school-finances.html