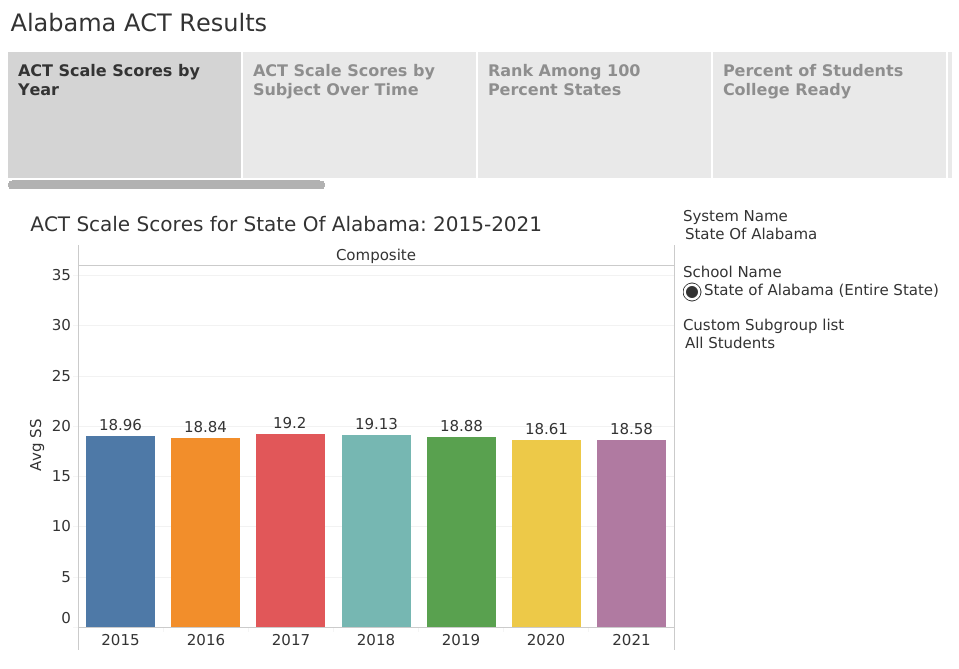

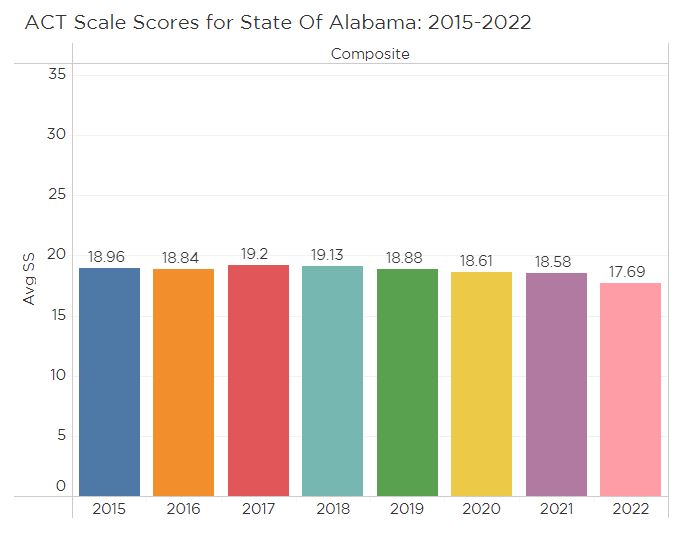

In Alabama and across the country, average scores on the ACT, the widely-used college readiness test, dropped for the pandemic-plagued Class of 2022, with Alabama scores reaching their lowest point since 2015.

Compared to the Class of 2021, Alabama public high graduates’ average composite score dropped by almost a point from 18.6 to 17.7 on a 36-point scale.

Printable PDF version available here.

That’s down from a high of 19.2 reached by the Class of 2017. The 2022 drop was sharper than but parallel to a half-point decline in the national average ACT score. ACT reports that the 2022 composite is the lowest national score in over three decades. The percentage of students rated college ready also dropped in every tested subject.

In Alabama, only 12.5% of seniors in the Class of 2022 scored at or above the college-ready benchmark in all four subjects. The subject with the highest college-ready rate was English, in which 40% of students met or exceeded the benchmark. In math, only 16.9% met the college-ready standard.

This PARCA analysis of ACT results includes interactive charts to explore and compare the performance of your local school and school system. Use the tabs above the graphs to explore different views of the data. Use the menu options on the right to change the subject being viewed or toggle through results for various demographic subgroups.

Why the drop in scores?

The most immediate explanation for the drop in scores is the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the Class of 2022 experienced a relatively normal senior year in 2021-2022, their sophomore and junior years, key ACT preparation and testing years, were disrupted.

In their sophomore year, in-person schooling ended abruptly in March 2020. Their junior year, which began in the fall of 2020, featured an uneven mix of remote and in-person learning. All Alabama juniors take the test in the spring, with some retesting into the senior year.

At the same time, many colleges dropped the requirement that students take a standardized admission test. So, students who previously would have taken the test several times in hopes of improving their scores were less motivated to do that.

On average, students who take the test multiple times improve their scores. According to ACT, the number of Alabama students taking the test three or more times declined from approximately 21,000 in 2017 to 13,000 for the graduating class of 2022. The results presented in this dataset and previous years are based on the highest scores achieved by graduates.

The drop in scores was prevalent across most Alabama schools and systems. There was no discernable pattern in the performance decline across schools and systems. Neither the socio-economic mix of the student population, per-student funding, or previous ACT score performance correlated with the changes.

Among demographic subgroups, White and Hispanic students saw steeper drops in performance than Blacks and Asians. As with most standardized tests, score gaps exist between racial, ethnic, and economic groups. On average, Blacks and Hispanics earn lower test scores, and a smaller proportion of test-takers in those groups reach the college-ready benchmark. Asians, on the other hand, outscore Whites.

Students from economically disadvantaged households are also less likely to earn a college-ready score than students who aren’t economically disadvantaged.

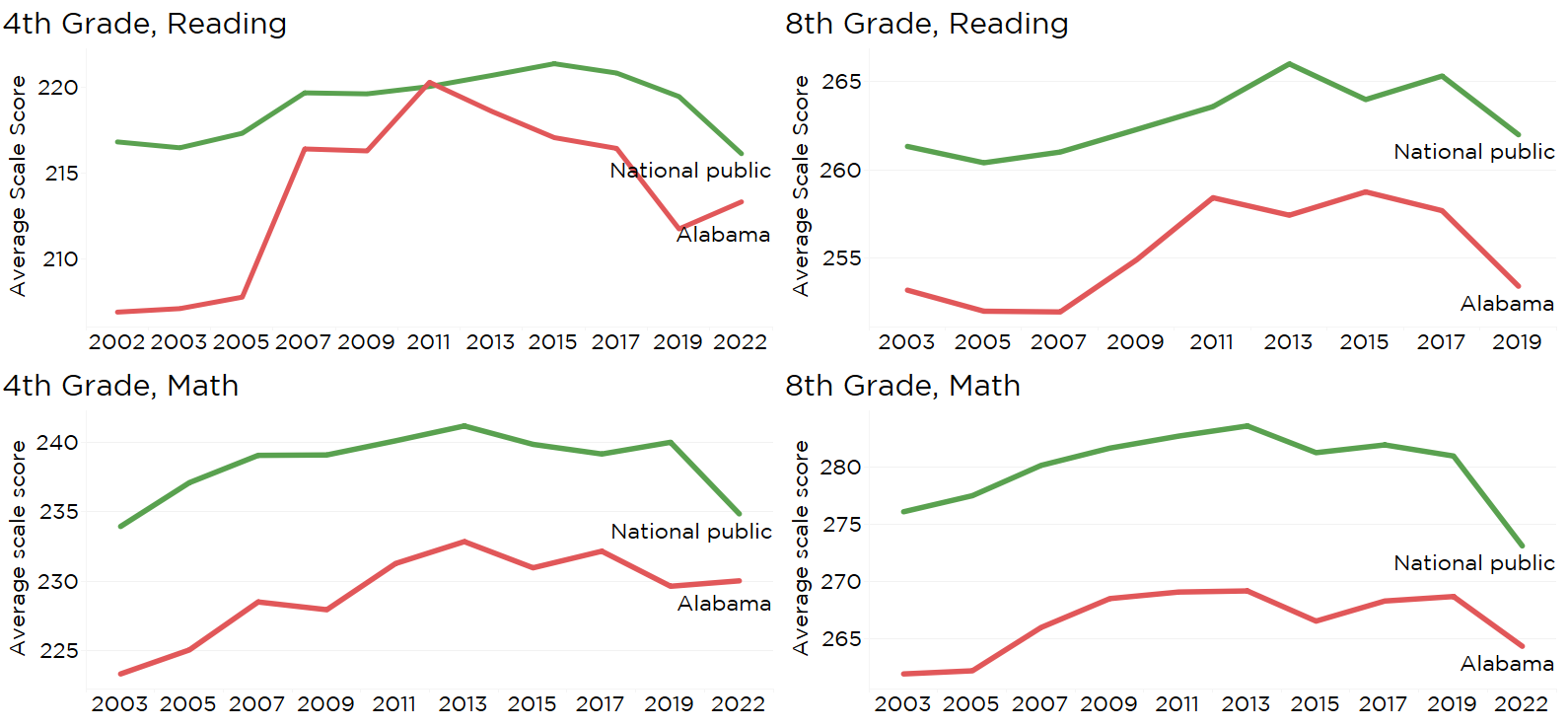

While the pandemic’s disruptions are the most immediate and obvious cause for declining scores, the downward trend in performance in Alabama and across the country predates the pandemic. What would have caused scores to rise in Alabama through 2017 and then decline? What factors would be so widespread that scores across the country on all four subjects could be affected?

ACT points to the declining percentage of high school students taking four or more years of core classes: four years of English and three or more years of math, social studies, and the natural sciences. Across demographic groups, students who take the full complement of core academic classes perform better on the ACT.

Why is the ACT important?

Many colleges use a student’s ACT score as a factor in admissions and as a qualification for scholarships. The ACT tests student skills needed for college success in four subject areas: English, reading, math, and science.

Each subject test is scored on a 36-point scale, and the subject scores are averaged to form a composite score. Through research, ACT established a benchmark score in each subject. Scoring above the benchmark is associated with having a 50% chance of obtaining a B or higher in the entry-level course in the subject area. Alabama tests all juniors as a way to encourage and support college aspirations among students and also as a measure of how well high schools are preparing students for college.

The ACT has been taken by all Alabama public school students since 2015 when the state began giving the test to all high school juniors. Because all students in Alabama take the test, the state’s scores shouldn’t be compared to the national average or to other states where the test is only taken by a subset of students, those applying to college.

The ACT serves as one of several measures of college and career readiness for students. Students whose score meets or exceeds the college-ready benchmark on one of the subject area tests are deemed college ready.

By giving all students the ACT, the state provides an opportunity for all students, regardless of wealth or family background, to take the test and consider pursuing a college education. Performing well on the ACT can attract the attention of colleges seeking and qualifying students for scholarships. Alabama is one of 16 states that test all or most high school students using the ACT.

The ACT also serves as a measure of how well high schools are doing at preparing students academically. Federal and state governments require a standardized test as part of their accountability requirements, and Alabama uses the ACT as its measure.

The ACT’s role in accountability and the decline in scores has some in the education community advocating for replacing the ACT.

At March’s Alabama State School Board meeting, at least two board members questioned whether the ACT was the proper test for accountability purposes. The ACT is designed to predict student preparation for success in college-level classes and doesn’t necessarily reflect the content required by Alabama’s course of study.

At the same time though, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey has set goals for raising Alabamians’ level of educational attainment. Some rise in attainment levels can be accomplished through technical training. The resulting credentials can improve income and career path. But a bachelor’s degree or higher still provides a more significant boost when it comes to better job prospects over the course of a lifetime. So, raising college-going and competition rates remains a key priority.

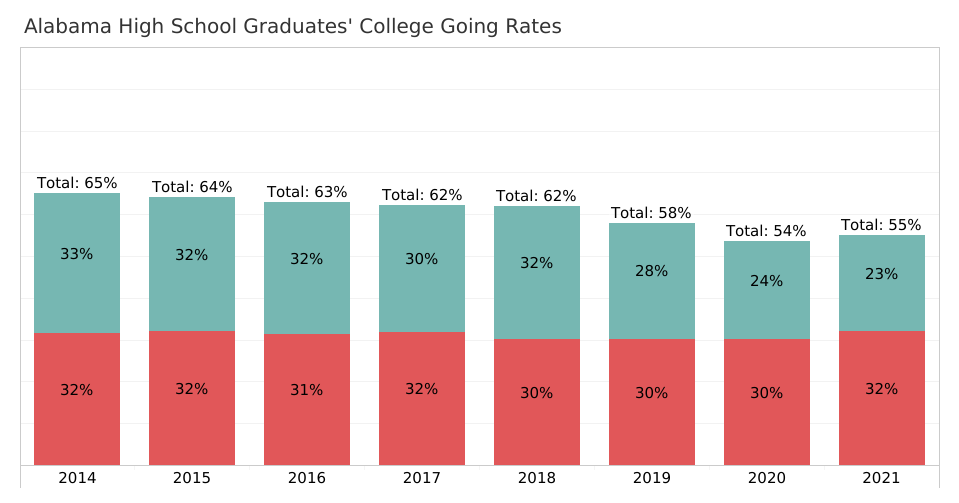

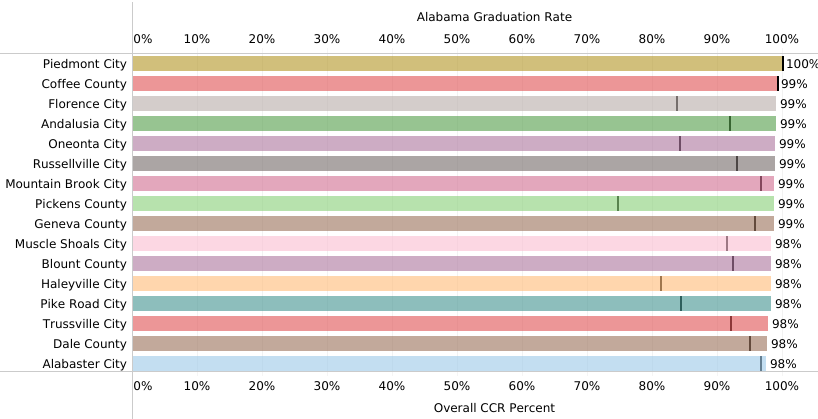

And despite the fall in scores on the ACT over time, Alabama’s high school graduation rate has increased over the same period, and the percentage of those graduates going on to four-year college has remained steady. Those two factors have meant the number of Alabama students proceeding on to four-year college has increased, despite the overall student population trending down. Meanwhile, the pandemic and the high demand for workers have led to a drop in the number and percentage of students going straight into two-year colleges. That’s not uncommon. In periods of low unemployment, more people are drawn directly into the workforce. For a more detailed analysis and discussion of college-going in Alabama, you can consult PARCA’s analysis of the most recent college-going rates.