PARCA Believes

Alabama can do better.

Alabama Public Opinion Survey 2021

PARCA’s 2021 public opinion survey finds a growing majority of Alabamians support spending more on education but a lack of consensus on how to pay for the increase.

Among the findings:

Taxes

- 61% of respondents say upper-income Alabamians pay too little in state taxes. The percent of respondents who believe upper-income earners pay too little increased by 10% from 2020.

- 53% say lower-income earners pay too much, up from 40% in 2016.

- 49% say they pay the right amount of taxes, compared to 57% in 2016.

- Despite Alabama’s low per capita tax yield, 69% of residents believe they pay the same or more taxes than people like themselves in other states.

Public Education

Alabamians believe education is the most important service state government provides, but its lead over other services is declining.

- 44% rank education as the most important service, while 31.3% rank healthcare No. 1.

- 78% believe the state spends too little on education, compared to 74% in 2019 and 68% in 2013. Large majorities in every subpopulation have this belief.

- 69% support increasing taxes to support education, but no single tax increase option garners majority support.

- This year, respondents were asked what supplemental programs might improve education. No program received a majority response, but the top priorities were expanded tutoring, increased technology funding, and more mental health counseling.

- When asked what respondents’ top priority for new education funding would be, the highest percentage (41%) said that new revenue should go to increasing salary and benefits for teachers

- 59% say local boards of education are best suited to decide how education dollars are spent.

- Respondents believe that the local board of education are best suited to decide school spending, school policy, and school closings.

Other notable education findings:

- 77% believe that taxes on Internet sales should be distributed to local schools in the same way as sales tax revenue from brick-and-mortar sales.

- Alabamians are almost evenly split on tax-funded vouchers to pay for private school tuition. However, 61% of Alabamians believe vouchers, if allowed, should be available to all students.

Trust in State Government

Alabamians’ trust in state government improved slightly compared to 2019 but is still well below rates reported in the early 2000s.

- 77% support keeping the General Fund and Education Trust Fund separate, down from 80% in 2020 and 82% in 2019, but still well above the 69% reported in 2016.

- 63% believe state government officials do not care about their opinions, down from 66% last year. This compares to a low of 55% in 2008 and a high of 74% in 2010.

- 61% believe they have no say in state government, up from 55% last year, but well above the low of 43% in 2008.

Stop the Slide, Start the Climb: Concepts to Enable Alabama Students to Achieve Their Fullest Potential

In March, the nonprofit Business Education Alliance commissioned PARCA to provide research describing the unprecedented challenges and opportunities in education faced by the state in this moment.

For more than a year, schools have coped with the Covid-19 pandemic: reshuffled learning environments, the unknowns of delivering education digitally, and the disruptive and unequal effects that those conditions have had on student learning.

Meanwhile, the schools are working to meet the demands of the Alabama Literacy Act, the 2019 law that requires all children to be reading at grade level by the end of third grade in order to be promoted.

At the same time though, to meet those daunting challenges, the state and federal governments are making an unprecedented amount of money available. For that investment to pay off, the money must be spent with care and forethought if Alabama is to seize this generational opportunity,

Read the full Business Education Alliance report here: Stop the Slide, Start the Climb: Concepts to Enable Alabama Students to Achieve Their Fullest Potential

2020 Kids Count Data Book provides roadmap for helping Alabama children

VOICES for Alabama’s Children recently released its 2020 Alabama Kids Count Data Book last month. This annual statistical portrait is meant to provide a roadmap for policymakers who seek to improve the lives of Alabama’s children. PARCA provides research support for the project.

The Data Book can be used to raise the visibility of children’s issues, identify areas of need, set priorities in child well-being, and inform decision-making at the state and local levels.

See how children in all 67 counties of our state are faring in education, health, economic security, and more.

Proposed Statewide Amendment Analysis for November 3

When voters go to the polls on November 3, they will not only be voting in the primary race for President, Vice-President, one U.S. Senate seat, seven U.S. House of Representatives, multiple state judicial positions, and various other state and county offices, but voters statewide will also be asked to vote on six new amendments to the Alabama Constitution of 1901. An additional 36 amendments to the state constitution will appear on the ballots of individual counties across the state.

As always, PARCA provides a high-level analysis of each statewide amendment. We study the ballot wording, but also the authorizing legislation behind the language. We do not make recommendations or endorsements, rather we seek to understand the impact of the proposed changes and the rationales for them.

The Alabama Constitution is unusual. It is the longest and most amended constitution in the world. There are currently 948 amendments to the Alabama Constitution. Most state and national constitutions lay out broad principles, set the basic structure of the government, and impose limitations on governmental power. Such broad provisions are included in the Alabama Constitution. But Alabama’s constitution also delves into the minute details of government, requiring constitutional amendments for basic changes that would be made by the Legislature or by local governments in most states. Instead of broad provisions applicable to the whole state, about three-quarters of the amendments to the Alabama Constitution pertain to particular local governments. Amendments establish pay rates of public officials and spell out local property tax rates. An amendment from a few years ago, Amendment 921, granted municipal governments in Baldwin County the power to regulate golf carts on public streets.

Until serious reforms are made, this practice will continue, and the Alabama Constitution will continue to swell.

Read the full report here.

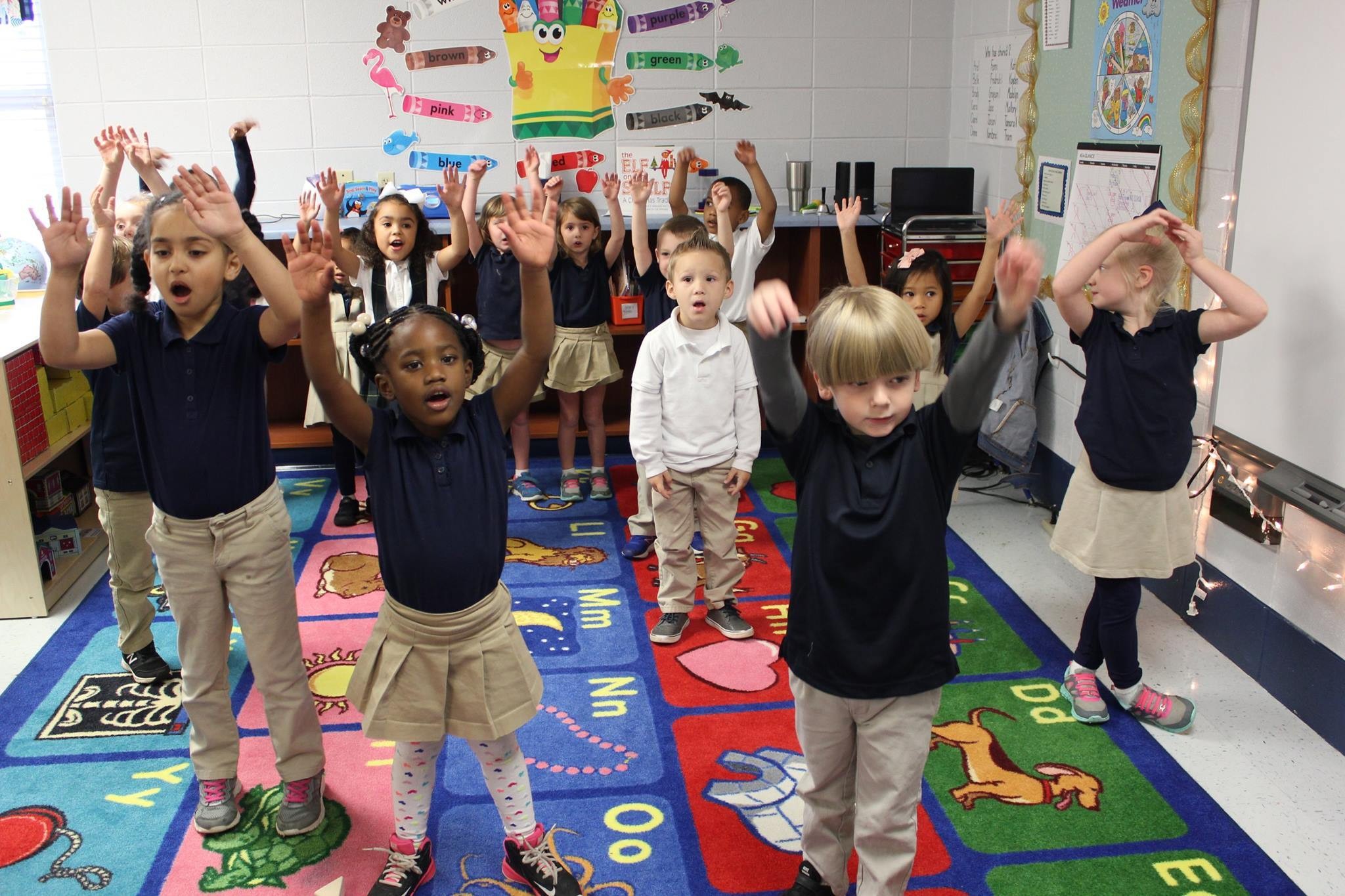

Alabama First Class Pre-K Research Gains National Exposure

The National Institute of Early Education Research (NIEER) at Rutgers University has recognized research on the persistence of the impact of First Class Pre-K.

Researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, PARCA, ThinkData, and the Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education published a peer-reviewed article in the International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy showing the persistence of gains in math and reading for students who received First Class Pre-K. This article is the culmination of several years of work involving five cohorts of students over time.

The article, written for an academic audience, offers a detailed statistical analysis of recent findings of the research team already shared with policymakers and pre-K advocates in Alabama and authored by UAB, the Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education, and PARCA.

Results indicate that children who received First Class Pre-K were statistically significantly more likely to be proficient in both math and reading compared to students who did not receive First Class Pre-K. Further, there was no statistical evidence of fadeout of the benefits of First Class Pre-K through the 7th grade, indicating the persistence of the benefits into middle school.

You can read the published article here.

To read previous research about additional academic benefits of Alabama First Class Pre-K, especially as it pertains to educational equity, click here.

COVID-19 and Public Education: Lessons Learned Last Spring

Alabama schools are set to re-open in August, with plans for local systems to offer educational services through traditional on-campus schools, remote on-line education, and a hybrid of traditional and remote learning options.

With the novel Coronavirus still spreading, all plans are subject to change. Already, the state’s largest system, Mobile County, and the Selma City School System have decided not to open school buildings and to proceed with only remote learning for all of its students this fall.

As policymakers, educators, and parents prepare for what will likely be a most unusual school year—including the possibility of additional shutdowns— PARCA gathered information from local reports and two major national polls that attempt to describe what parents and students experienced during the school closures this spring. As schools plan for the fall, these experiences are important to understand.

According to the polls, parents worried the online school experience was resulting in:

- learning loss and lack of academic advancement

- a lack of social interaction for students, negatively impacting student mental health

- inadequate contact between parents and teachers

- a mismatch between the resources provided by schools and the aid parents most needed

- increased inequities in the educational experience

The Shutdown

As COVID-19 spread this spring, schools across the country closed. By March 20, 45 states had closed all schools. By early May, the number climbed to 48 states and the District of Columbia—affecting more than 55 million students. Only Montana and Wyoming allowed schools to remain open, although some systems in those states did close. 1

Almost overnight, schools entered uncharted waters. States, systems, and local schools mobilized resources for parents and students and reimagined teacher-student interaction. For most schools, this entailed some version of virtual education.

According to a Gallop Survey conducted in March 2020, 70% of parents of K-12 students not in school at that time reported their child was participating in an online education program run by his or her school. The survey found that among parents whose children were not enrolled in a formal online education program, 52% were homeschooling with their own materials, 25% were using a free online learning program not associated with their child’s school, and 35% were not engaged in any formal education. 2

Some schools had the capacity to respond to COVID-19 closures comparatively easily. That includes schools in Alabama and elsewhere that were already designed as virtual schools. Other systems in other parts of the country are more experienced in online education because of long winter breaks with harsh weather. Conversely, most schools, educators, parents, and students were thrust into a new learning environment for which they were little prepared.

Parents and students around Alabama reported a wide variance in student experiences, varying according to system, school, grade, and teacher. Some reported students having more work than before the shutdown and spending hours each day with regular virtual check-ins. Others reported that work was considered optional or that students finished nine-weeks of work in just a few days. The long-term effects of the academic transition and the inconsistency of students’ experience will take time to assess.

Parent Reactions

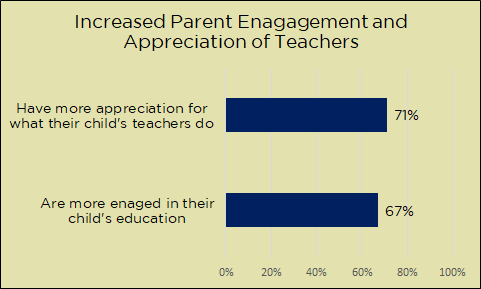

The national nonprofit educational organization Learning Heroes conducted a survey of parents in April and March 2020. The survey, which reached 3,645 parents from across the nation, was conducted in conjunction with the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS), and the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE).

Results show that parents, now in the role of educators or critical partners in their child’s learning, have gained a new appreciation for what teachers and schools do. 3

Figure 1

Some parents reported being overwhelmed, while others reported more involvement in their child’s learning has given them a healthy sense of engagement and better insight on how to help their children learn. These parents look forward to being more involved in schools and their child’s education once schools re-open.

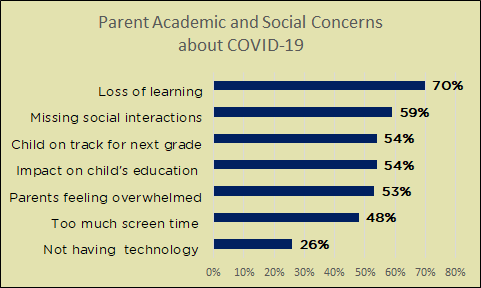

Academic Concerns – Loss of Learning Assessed

Seventy percent of parents expressed concern about the loss of learning and how this will be made up. Fifty-four percent are concerned their children will not be ready for the upcoming school year. These issues raise more fundamental questions about the nature of teaching and learning. High-quality teaching and learning can presumably occur in different forms. With state testing postponed, measuring the impact on student learning gain or loss will be complicated but is an important objective.

Figure 2

States such as California and South Carolina are planning to implement new tools for assessing learning loss. Quick, real-time assessments conducted by teachers in the classroom, or virtually, will likely be most effective. Assessments that take time to report results will have limited utility for teachers but may be instructive for administrators and researchers.

Researchers have tried to predict the magnitude of pandemic-related learning loss by analyzing normal summer learning loss — the degree of academic regression between the end of one school year and the beginning of the next – and treating the COVID shutdown as an extended summer. Some researchers estimate that students likely ended the school year with only 40% to 60% of learning gains achieved during a typical school year. [efn-note] M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Edworking Papers, May 2020. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University [/efn_note] Other studies estimated much lower losses. 4 5 6

Some experts believe the projected learning loss is over estimated.

They note that estimates using summer loss as a baseline are not taking into account the learning that occurred through virtual forums and support provided by schools this past spring. Likewise, most of the content students were expected to learn was already introduced to students by March, although students did not have an opportunity in class to practice skills, and develop mastery. Furthermore, teachers are prepared to work with students coming back at different levels of preparation after the summer break, so they will not be caught off-guard. At the same time, this will likely be much more challenging and will be taxing for teachers who are less prepared and motivated to work with diverse learners.

These same experts, however, are alarmed about the challenges facing beginning readers, who usually need continued re-enforcement throughout the year. This could affect future literacy rates and have implications for implementing Alabama’s Literacy Act in the lower grades. 7

Social and Mental Health Concerns

Parents expressed fear about the impact of COVID-19 on their children’s social-emotional well-being, and 59% worry about the impact of reduced social interactions. For young children in unsettled or abusive home environments, the school can be a safe place. Long-term absence from this safe place can become a source of heightened trauma with long term consequences.

Many children may be coping well, but medical experts are concerned about the stress and trauma children (and adults) are experiencing during the pandemic, especially those with underlying mental health conditions. School-aged children experienced sudden changes in their educational setting and routines. Many experienced shock. Some families have had the stress of sickness and death in their families as a result of the virus – though overall a relatively small percentage. Many more families are under financial strain. Concerns have been raised about abuse, neglect, loneliness, and isolation. The virus has affected every facet of the life of children and adults. 8

Symptoms of trauma in school-aged children can include:

| Physical Symptoms | Over-or under-reacting to stimuli (physical contact, doors slamming, sirens) Increased activity level (fidgeting) Withdrawal from other people and activities |

| Cognitive | Recreating the traumatic event (e.g., repeatedly talking about or “playing out” the event) or avoiding topics that serve as reminders Difficulties with attention Worry and fear about safety of self and others Disconnected from surroundings, “spacing out” |

| Social-Emotional | Rapid changes in heightened emotions (e.g., extremely sad to angry) Difficulties with controlling emotions angry outbursts, aggression, increased distress) Emotional numbness, isolation, and detachment |

| Language and Communication | Language development delays and challenges Difficulties with expressive (e.g., expressing thoughts and feelings) and receptive language (e.g., understanding nonverbal cues) Difficulties with nonverbal communication (e.g., eye contact) Use of hurtful language (e.g., to keep others at a distance) |

| Learning | Absenteeism and changes in academic performance/engagement Difficulties listening and concentrating during instruction Difficulties with memory 9 |

Parents can reduce the risk of stress by creating a calm, safe, and predictable environment, communicating and building a positive-supportive relationship with their children, and encouraging their children to develop self-regulation skills.

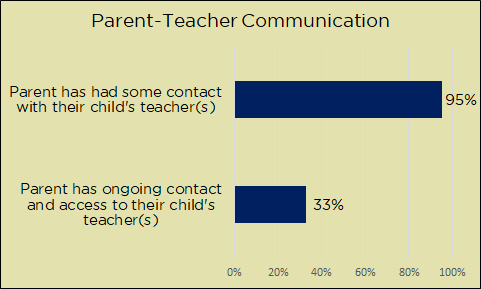

Teacher Interaction

Parents expressed concern about the lack of regular ongoing contact they and their children have with their children’s teacher(s). This is perhaps less critical for self-motivated students with highly resourceful parents or guardians with time devoted to learning at home. But many students depend on regular high-level teacher interaction. Parents indeed may have the will and skill to perform in this role but are working in fulltime jobs. Others express concern about not having the background to adequately support their children. Still, others may be in stressful life situations that rob them of the motivation and energy to serve in this role. In each of these situations more ongoing contact with teachers and community support specialists would likely make a significant difference.

Figure 3

Though parents find communication with teachers extremely helpful, the majority did not receive this support on an ongoing basis. Teachers have found themselves in uncharted territory for which they were not prepared. They too may not have the skills and background needed for online teaching and tutoring. The awkwardness of online communication and technical hiccups can generate additional frustration. Everyone is learning and adapting.

Resources Provided by the School

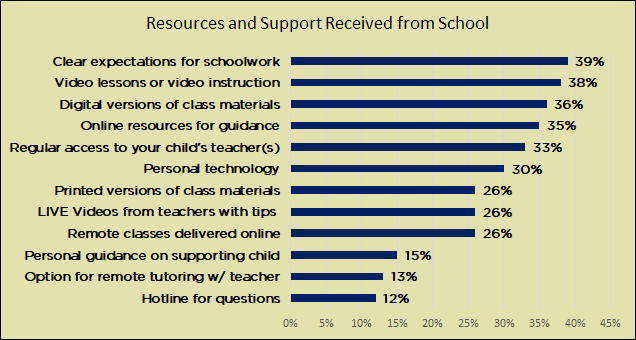

An especially important issue for schools this past spring was providing guidance and resources to parents to assist them in working with their children. The figure below shows the percent of parents indicating they received key resources from their child’s school during the pandemic this past Spring.

Figure 4

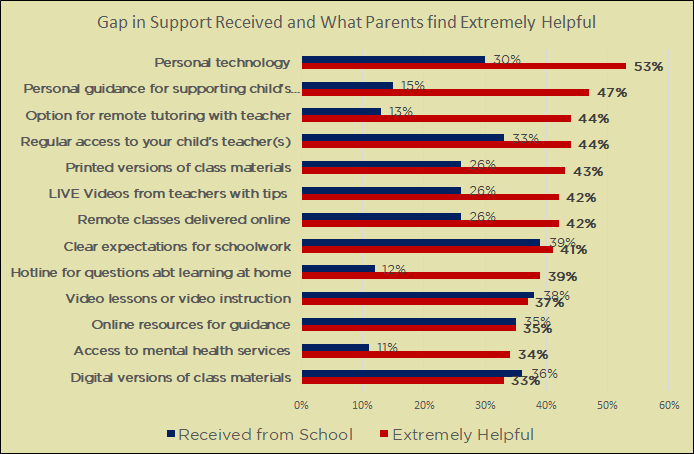

But sometimes what parents received was not what they needed or found most useful. In Figure 5 below, resources are ordered by the percent of parents who found the assistance useful (red bar), from highest to lowest, and the percent receiving the guidance or resource.

Figure 5

The most useful assistance included:

- school provided personal technology

- online guidance

- one-to-one tutoring with teachers

- ongoing regular contact with teachers

- printed versions of class materials

- remote classes delivered online

Parents found printed materials more helpful than digital materials.

The gap between what was offered and what was found most useful, when offered, was largest for the following:

- personal guidance in supporting your child’s learning at home

- remote one-to-one tutoring by teachers

- school provided technology

- access to mental health services

COVID-19 and Equity

A number of observers have focused attention on the profound inequities in education magnified by COVID-19. Systems vary in funding, resources, curriculum, extracurricular offering, teacher experience and in many other ways. These disparities are likely exacerbated when the home becomes, not by choice, the primary learning environment for all students.

Virtual education has the potential for system-by-system and house-by-house differences in capacity to compound each other.

Differences in capacity across households include the following:

- Income and educational attainment of parents.

- The knowledge and experience of parents, guardians, or other adults.

- The time and availability of parents, guardians, or other adults to actively facilitate or assist in their children’s learning.

- Family structure: One and two-parent families where responsibilities are shared.

- Relationships between parent-child, parent-teacher, and student-teacher.

- Access to communication, guidance, and support from teachers and schools.

- Access to community supports and enrichment.

- Access to computer technology and high-speed internet. Capacity and motivation to make use of these resources.

- Access to nutritional food daily.

These obstacles may be greater, but in no way limited, to lower-income areas.

The general public and government leaders most frequently cite a child’s school and teachers as the primary difference in their education. But research has long noted that children do not enter school as a blank slate, and that inequalities begin at birth as a result of different prenatal conditions, and too often are made worse during those early years before school. Children enter school with vastly different levels of preparation. The achievement gap, from this point of view, is a symptom of broader inequality, past and present. Improving education on campus and on-line and building a solid workforce calls for addressing these inequalities in the home and school. 10 Strauss, V. (2020). How COVID-19 has laid bare the vast inequities in U.S. public education. The Washington Post, April 14, 2020. /efn_note]

School Discipline and Race in Alabama

Black students face harsher disciplinary measures than white students for similar offenses, a PARCA review of public school disciplinary records has found. Meanwhile, Alabama is one of few states nationally, and the only state in the Southeast, that has no uniform statewide policies requiring due process when students are suspended or expelled.

Suspensions have been shown to increase rates of school failure.

Students with a record of numerous disciplinary infractions are at a higher risk for trouble in school and life. Research has shown that students experiencing early problems with attendance, academics, and discipline more frequently experience negative outcomes, such as leaving high school without a diploma or graduating, but unprepared for college or work. Such problems in school have also been linked to a greater likelihood of poor health and criminal activity.[1]

There is very little evidence showing positive impact of out-of-school suspensions on student behavior, and in many cases, they are more likely to cause more harm than good. Out-of-school suspensions are disproportionately applied to Black students, and potentially contributing to a pipeline that leads from school to prison.

Background

In 2018, PARCA Research Coordinator Joe Adams collected data from the Alabama State Department of Education (ALSDE) that included extensive disciplinary records for the school years, 2014-15, 2015-16, and 2016-17. Using these data, PARCA has found that students who are Black are more likely to receive out-of-school suspensions than white students for the same offense, and students who are white are more likely to receive the less restrictive in-school suspensions than Black students. These findings provoke concern considering the broader context of racial inequities in education, healthcare, criminal justice, corrections, employment, and housing conditions.

In recent years research has found significant differences in the use of suspension and expulsion based on race. These data, along with research showing the long-term negative impact of suspensions and expulsion, have led states to re-examine their disciplinary policies, though Alabama is behind this curve.

A report issued by the Education Commission of the States in 2018 found that most states are limiting the use of suspension or expulsion. [2]

- Sixteen states, plus the District of Columbia, limit the use of suspension or expulsion by grade level, usually by disallowing suspension or expulsion in the early grades. Alabama’s state regulatory statutes do not currently have such limitations. Though suspensions are more common in middle and high school, they also frequently occur in the lower grades in Alabama.

- Several states limit the use of exclusionary discipline for certain violations. Of those, about 17 states, plus the District of Columbia, prohibit suspension or expulsion solely for a student’s attendance or truancy issues. This limitation does not exist in Alabama. Suspension is a common disciplinary action for truancy and tardiness in the state.

- About 30 states, plus the District of Columbia, encourage districts and schools to utilize non-punitive, or more supportive, school discipline strategies. Of those, 22 states, plus the District of Columbia, mention the use of specific, evidence-based interventions — such as schoolwide Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS), restorative practices, Response to Intervention (RTI), trauma-informed practices and social-emotional learning. Alabama statutes do not address the school-wide programs cited above, though individual schools are choosing to implement PBIS, restorative justice, and other such programs, and the Alabama State Department of Education developed a guidebook to PBIS.

A student’s right to a fair hearing in the state is another important issue. Based on a 1975 U.S. Supreme Court ruling (Godd v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565 [1975]), students who are suspended or expelled have a right of due process to defend themselves in a fair hearing. Since this ruling, states have enacted policies to ensure local communities follow through and protect a student’s constitutional right to a hearing. Some states outline very detailed procedures for local boards to use. Most directly state that no student will be suspended or expelled for more than 10 days without an objective hearing. Alabama is one of the few states nationally and the only state in the Southeast that does not have uniform statewide procedures that must be followed before removing a student from school. See https://safesupportivelearning.ed.gov/school-discipline-laws-regulations-state.

Some local boards in the state have developed due process procedures, with varying levels of clarity, and some have not. If a system fails to protect due process, the only recourse is a legal proceeding. Under these circumstances, it is conceivable that a student could be suspended, or even expelled, because of an infraction in which they are innocent, without a hearing and investigation into what happened.

Alabama lawmakers recognize these issues are a problem.

In the 2020 session of the Alabama Legislature Senate Bill 189 proposed limits on suspensions and expulsions. The bill proposed:

- Requiring local boards of education to hold a hearing when a student is expelled or suspended for more than 10 days.

- Prohibiting suspension of students enrolled in Pre-K through the fifth grade unless the safety of other students was endangered.

- Prohibiting suspension for truancy or tardiness.

At the close of the shortened 2020 legislative session, SB 189 had passed the Senate and was referred to the Education Policy Committee in the House of Representatives.

Analysis of Disciplinary Infractions

The dashboard charts below show data on reported infractions in Alabama schools, beginning with the number of reported incidences for all specific infractions collected in the state Student Incident Report (SIR) system. This includes charts showing the infractions with the highest number of incidents, as shown below.

Disturbances or disruptions generated the most reported infractions all three years, followed in 2017 by assault, disobedience, and defiance. These categories give some idea of the offense committed, but with limitations. Local schools and systems may vary in how they interpret these categories. Mystery offenses are unspecified offenses.

The total number of reported infractions by race are shown below. Students who are Black comprise 33% of students in Alabama’s public schools; however, they account for 60% of all reported disciplinary incidents.

Extensive research has demonstrated that students in low-income or poverty households are more likely to experience family stress, verbal and physical abuse, neglect, drug and alcohol use in the home, and other sources of emotional pain and trauma—and may develop different responses or reactions to stressful situations.[3] Cultural conflicts between students and teachers and administrators may also result in a disproportionate number of Black students cited for infractions, as well as teacher-student exchanges that escalate and fail to properly address situations that arise. [4] [5]

Responses to Disciplinary Incidents in Alabama Public Schools

The following dashboard charts show the punitive actions (dispositions) for all offenses in Alabama, as found in the data provided to PARCA by ALSDE.

Among the incidents that are reported to the state in the SIR data, the preferred disposition for responding to the vast majority of incidents was suspension. Out-of-school suspensions are more common than in-school suspensions, though the 48-40% split is not an alarmingly large gap. Both are used frequently.

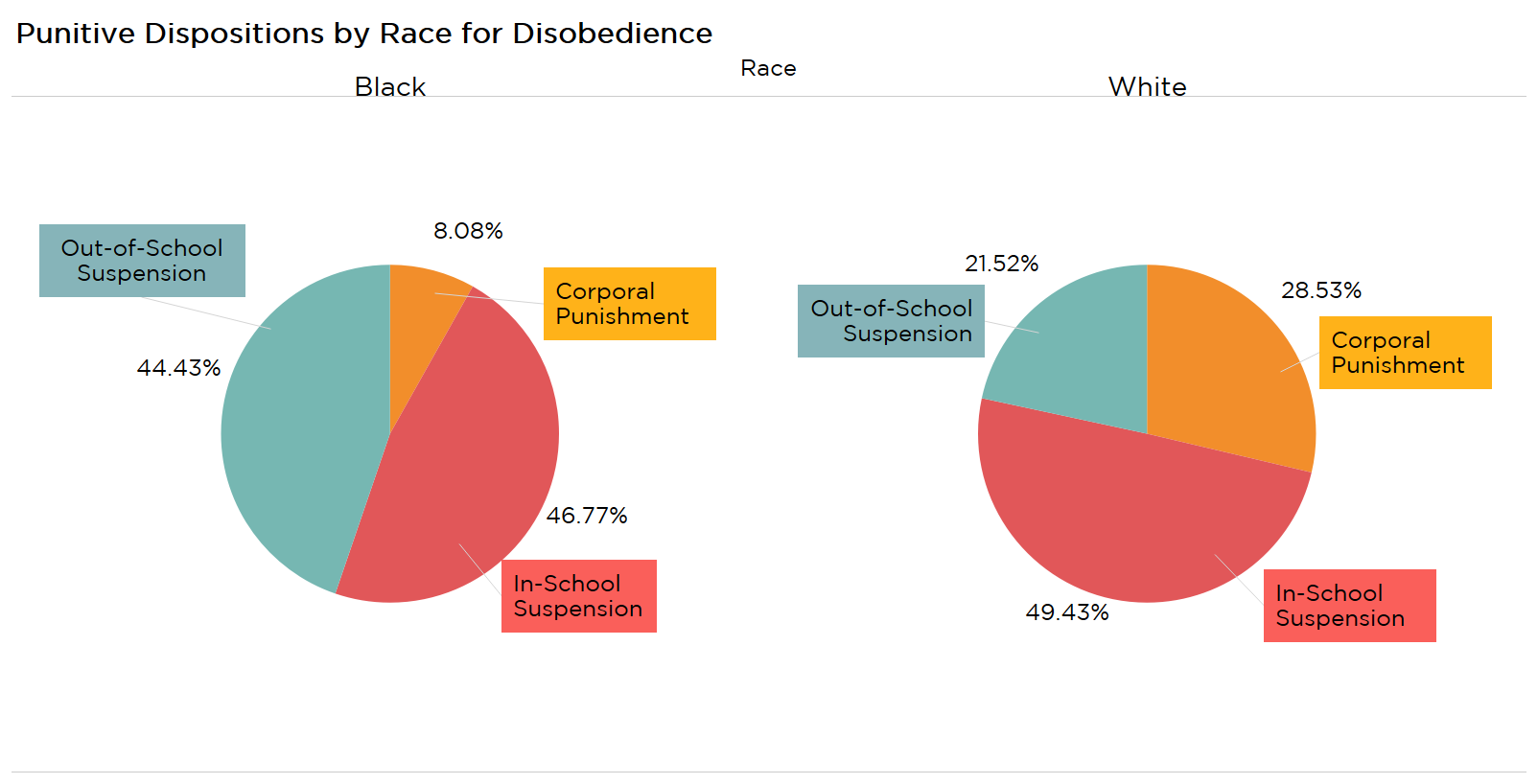

More problematic are dispositions by race. The following dashboard chart displays state-level disposition data for Black and white students, divided between schools that utilize corporal punishment and those that do not. In Alabama, systems that use corporal punishment tend to be majority white systems. Majority Black systems are more likely to prohibit corporal punishment. Systems with greater racial diversity are mixed in their use of corporal punishment. Consequently, by default, Black students are less likely to receive corporal punishment.

The proportion of Black students receiving out-of-school suspensions is markedly higher than for white students, who are more likely to receive the less severe in-school suspensions.

These patterns hold when looking at dispositions for specific infractions committed by both Black and white students. Looking at dispositions recorded for nearly 60 infractions, in 90% of the infraction types, Black students were more likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than white students for the same infraction.

The dashboard charts show the percentage of students receiving out of school suspension by race for the most common infractions.

Infractions are ordered from the highest gap to the lowest between the percentage of offenses cited for Black and white students punished with out-of-school suspensions for the same offense. This order varies somewhat each year. Black students are more likely to receive an out-of-school suspension than white students for all of the 10 most common infractions.

Among the most frequently occurring infractions, the gap between cases in which Black and white students received out-of-school suspension was largest in 2017 for tobacco-related offenses and smallest for drug-related offenses. In 2016, the gap was largest for disobedience. Infractions for disobedience resulted in out-of-school suspension in 19% of the cases involving white students, but when Black students committed the offense, out-of-school suspension was used in 47% of the cases.

This is a gap of 28 percentage points – showing that Black students were twice as likely to be removed from school than white students for this same offense.

The charts below provide more detail for different infractions. Use the filters to explore results for all infractions. Examples are posted below.

Suspensions – Background and Research

In the 1990s and early 2000s, schools across the United States employed exclusionary discipline, namely in-school and out-of-school suspensions, at increasing rates. Suspensions are a punishment for “bad behavior” and may have also been seen as a “cooling off period” for students. In other situations, suspensions may be used to bring more control to a hostile situation and create easier conditions for maintaining a safe learning environment. In any case, suspensions are a signal to parents/guardians that their children are demonstrating behavioral problems.

With in-school suspensions, students are removed from their regular class but still attend school in a designated classroom or another school in the system. Thus, the students are still receiving some form of instruction and supervision. Out-of-school suspension prohibits the student from attending school for a temporary period, usually five or fewer days. Very serious infractions may result in expulsion—removing the student from the school system.

Clearly, there are situations where the safety of students and school personnel must take priority and call for removing a student from school grounds. However, there is very little evidence supporting the positive impact of suspensions on student behavior.[6] Researchers documenting the increased use of suspensions over the last three decades found they were not effective in changing student behavior and were associated with other negative outcomes, including lower academic achievement, grade retention, increased drop-out rates, and involvement with the juvenile justice system.

Critics argue that suspensions are adversely related to student learning. Suspensions remove students from the classroom or an optimal learning environment. Achievement gaps are widened as out-of-school suspensions are disproportionately given to students who are male, Black, economically disadvantaged, from single-parent families, or who have disabilities. Suspension can create more sense of separation between the student and school, increase feelings of not belonging, and negative feelings about school. Unsupervised students are vulnerable to getting in more trouble and consuming alcohol and drugs. Suspensions can cause further stress for children and a sense of isolation.

Suspension can be a way to remove the “problem” without addressing the underlying causes.

References

[1] Balfanz, R. (2009). Putting Middle Grades Students on the Graduation Path: A Policy and Practice Brief. Everyone Graduates Center and Talent Development, Middle Grades Program. Middle School Association.

[2] Rafa, A. (2018). 50-State Comparison: State Policies on School Discipline. Education Commission of the States. August 28, 2018

[3] Nixon, B. (2012). Stress Has Lasting Effect on Child Development. The Urban Child Development Institute.

[4] Investigating the Association between Home-School Dissonance and Disruptive Classroom Behaviors for Urban Middle School Students. The Journal of Early Adolescence, Vol. 38, pp. 530-553. April 2018. By K. Tyler, J. Burris, and S. Coleman.

[5] Classroom Disruptions, the Teacher-Student Relationship and Classroom Management from the Perspective of Teachers, Students, and external Observers: A Multi-Method Approach. In Learning Environments Research, Vol. 22, Issue 1, pp. 101-116, April 2019. By M. Scherzinger and A. Wettstein.

[6] Ritter, G. (2018). Reviewing the progress of school discipline reform. In Peabody Journal of Education, Vol. 93, No. 2, p. 133-138, 2018.

2019 ACT WorkKeys: Preparing Students for Work in a Time of Uncertainty

High school seniors and recent graduates are preparing to enter a workforce that has been disrupted, hopefully only temporarily. In a matter of weeks, the nation has gone from record low unemployment to levels not seen since the Depression. Employers are adapting to a new set of work conditions and the demand for new skills appropriate for remote work is rapidly rising.

The WorkKeys Assessment may now be more valuable than ever in helping employers assess the practical skills and adaptability of potential hires.

WorkKeys Assessments in Alabama

WorkKeys is a standardized test given to 12th graders in Alabama public schools. The assessment is meant to measure skills relevant to many of today’s work environments. This is a test that generates positive results in Alabama with steady progress.

WorkKeys is one of the measures through which a student can be designated as College and Career Ready in the state. They may not have the specialized training needed for particular occupations, but if a student earns a certification at the higher levels, the measure should increase the confidence of employers in hiring staff who are adept at applying useful cognitive skills and knowledge to applied work tasks in contemporary work settings.

The Assessments. The assessments consist of three tests of applied cognitive skills which are relevant, according to ACT’s research, to over 20,000 occupations:

- The Applied Math test

- The Graphic Literacy test

- The Workplace Documents test (applied reading for understanding)

Students are awarded a National Career Readiness Certification if they score a Platinum, Gold, Silver, or Bronze score on the WorkKeys. Platinum is the highest level, followed by Gold, Silver and Bronze.

After modifications to the 2018 assessment created significant fluctuation among the different certificate levels, the results in 2019 showed steady gains in the Platinum and Silver levels, and slight decreases in the percent of students earning Gold and Bronze certificates, as well as the percent of students not receiving any certificate.

In Alabama students earning a Silver certificate or above are considered career ready.

Highlights of the WorkKeys test results for the Class of 2019 include:

- 66% of Alabama high school graduates were

deemed workforce ready as measured by the ACT WorkKeys assessment, an improvement over 64 % in 2018.

- At 94%, Hartselle had the highest percentage of workforce-

ready

- The Silver Certificate continues to be the level with the highest percentage of students.

WorkKeys is emerging as another source of information for making employment decisions and helping prospective workers learn about strengths and weaknesses and opportunities for growth. Using job profiling data provided by ACT, the Alabama Department of Labor maintains data listing the median WorkKeys scores for high demand occupations requiring an associate’s degree or less.

2019 Assessment Results

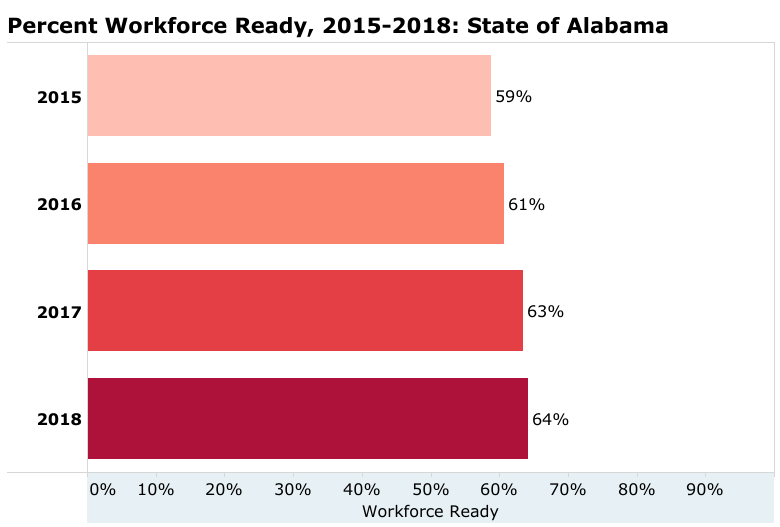

The following charts show the percentage of graduates in Alabama who demonstrated workforce readiness on WorkKeys assessments.

In 2019, 66% of high school graduates taking the assessment were deemed workforce ready. This percent has steadily increased since 2015.

Workforce Ready at the Local Level

The following charts focus on workforce readiness among graduates at the local level. A county view is appropriate when thinking about the quality of a local workforce.

Of course, local school systems and schools are the places where students develop knowledge and skills related to work readiness.

Listed below are the top ranked systems based on workforce readiness assessed through WorkKeys:

- Mountain Brook City – 95%

- Arab City – 94%

- Satsuma City – 94%

- Cullman City – 89%

- Hartselle City – 87%

- Trussville City – 87%

- Homewood City – 86%

- Madison City – 86%

- Brewton City – 85%

- Guntersville City – 85%

Mountain Brook has made positive gains over the past two years and appears to remain committed to WorkKeys as a valuable assessment.

With committed effort, WorkKeys is an assessment where systems can show growth, as demonstrated by a variety of systems and schools in Alabama.

A number of large and medium-sized systems made noteworthy gains over 2018. Auburn City topped all, showing remarkable gain (up by 24 percentage points).

Among the schools, Loveless Academy continued its top ranking with 100% of students deemed workforce ready. Top schools include:

- Loveless Academic Magnet High School, Montgomery County – 100%

- New Century Technology Magnet High School, Huntsville City – 95%

- Mountain Brook High school – 95%

- Brewbaker Technology Magnet High School, Montgomery County – 94%

- Arab City High School – 94%

- Ramsay High School, Birmingham City Schools – 94%

- Satsuma High School, Satsuma City Schools – 94%

A number of large and moderate sized high schools experienced positive gain over 2018. This is an area of growth for a number of schools failing to show gains in more purely academic assessments.

Change in Certificate Levels

Students are deemed workforce ready if they achieve certification at the Platinum, Gold, or Silver levels. The charts show that the percentage of students at the Gold and Silver levels increased moderately from 2015 through 2017, with Platinum barely making a dent. After modifications to one of the tests in 2018, Gold and Platinum level certificates grew substantially, while Silver certificates dropped significantly. The percent at each level in 2019 is comparable to 2018, but with positive gains in Platinum and Silver. The percent of students at the lowest level, with no certificate, continues to drop.

Overall, this resulted in a higher percent workforce ready for the state, with a positive trend toward higher certification levels.

Change in Certificate Levels at the System Level

Platinum: Mountain Brook and Homewood City finished in a tie with the highest percent of Platinums, followed by Madison City, Hoover, Hartselle and Arab City. Aburn City climbed up in 2019 to join these state leaders.

Gold: Oneonta, Arab, and Mountain Brook are the systems with the highest percentage Gold. Though the majority of systems decreased at the Gold level, a number of systems increased their percentage. Leading the way in percentage point gain was Chickasaw City and Jacksonville City, followed by Piedmont City and Talladega County. Arab City continues to show nice gains as well.

Silver: This is the minimum level to be counted as workready. A number of less affluent systems are among the leading systems for Silver certificates. Systems with the highest percentage at this level include Opp City, Satsuma City, Haleyville City, and Lamar County. The vast majority of systems increased in the percentage of students earning Silver certificates in 2019, led by Opp City.

Subgroup Analysis

Analysis of subgroup results shows a continuing disparity between subgroups. Use the filters to see how systems differ in subgroup performance. Some schools may be better at assisting struggling groups than others.

The highest performing groups include students who are Asian, white, non-poverty, female, and military-affiliated. The lowest-performing groups are black, migrant, and special education. While all of the racial groups are increasing their percentage of workforce ready, black students have made the most gain since 2015.

Females continue to outperform male students, though both have shown comparable positive growth since 2015.

In looking at trends, all racial groups are showing progress from year to year, especially Asian and black students.

Finally, special populations are also showing positive growth in workforce readiness, especially students qualifying for free lunch (poverty) and students living in foster homes.

Discussion

The 2020 report, Education Matters, written by PARCA on behalf of the Business Education Alliance, recommends increasing the awareness of WorkKeys as a valuable tool for employers, communities, and schools.

In addition to the assessments, WorkKeys provides a full suite of resources that can help provide training for teachers, test preparation for students, and design career-related curricula to help students improve their “hard” and “soft” skill levels. ACT Career Ready 101 is designed to help teachers bring work readiness skills into the classroom. This raises questions about how students become workforce ready in school. Beyond special resources for preparation, is the curriculum and content delivered in schools changing to strengthen career readiness, even in traditional academic subjects?

The long-term future of WorkKeys will be determined by the continuing value educators give to these assessments and suite of resources, and the degree to which employers value WorkKeys. A growing number of communities and employers are aware of the utility of WorkKeys, but this still varies across the state. Currently, schools also vary in the degree to which they emphasize WorkKeys.

College Freshmen in Need of Remedial Education

The percentage of first-time college students from Alabama public high schools assigned to remedial courses in math and English has continued to drop overall and, in the most recent data available, dropped dramatically for those attending two-year colleges, according to data from the Alabama Commission on Higher Education (ACHE). Graduates studying in four-year colleges needing remediation increased for the first time in several years.

The data follows Spring 2018 graduates of Alabama high schools who enrolled in Alabama public colleges in the fall after graduation. The data shows that 26% of those who enrolled in higher education were required to take a course in either remedial math or remedial English or both. That’s down from 32% five years ago.

Remedial courses are primarily offered in English and math. They are designed to bring students up to the educational level needed to succeed in a college course. Students assigned to remedial math and English cannot proceed on to college-level courses in those subjects until they have passed the remedial courses. Colleges vary in the degree to which they allow students to take courses in other subjects simultaneously with their remedial courses. Some students enter with a poor background in one of these subjects but not the other. Some may have a specific learning disability in math, for example, or just never gained the foundation needed for higher math, but excel in English and other courses.

Interactive charts are presented below. Each panel presents a different view with the capacity to drill down from the state level to the system and school level, and for schools within a system. Bear in mind that the ACHE report only captures high school graduates who enrolled in the fall after their graduation in Alabama public colleges. The remediation rates for schools that send significant numbers of students to private colleges or to out-of-state colleges will not necessarily reflect the outcomes for the entire graduating class.

A higher percentage of students take remedial math than remedial English. But the progress shown for math over the past year, down from 24% to 21% in remediation is significant, given that in the past English has shown more improvement. The percentage of students taking remedial English remained the same at 12%.

At this point, both subjects have made similar progress in reducing the percentage of students taking remedial courses. Math dropping from 26% in 2013 to 21% in 2018, and English dropping from 17% to 12%. Check it out in the charts. and use the filters to drill-down and make comparisons.

The next set of charts provide remediation rates for all systems and schools in math and English over time.

Finally, take a look at the numbers in two-year and four-year colleges.

Thirty-three percent of Alabama’s high school graduates enrolling in the state’s public two-year colleges were assigned to remediation in 2018, a significant decrease from 41% in 2017. Since 2013, that percentage has dropped from 46% to 33%.

At the same time, remediation among Alabama’s high school graduates attending four-year colleges increased to 18% in 2018, up from 14% in 2017, and 17% in 2017. This reverses a downward trend and becomes the highest percentage assigned to remediation in the state’s four-year colleges over the past six years.

Over time, approximately 75% of Alabama’s high school graduates assigned to remediation attend the state’s public two-year colleges, and 25% attend the state’s public four-year colleges. This ratio has remained steady for years, but these numbers began to shift in 2018. The ACHE data shows that for 2018, two-year colleges account for 65% of graduates taking remedial courses and four-year colleges up to 35%.

This may be an anomaly in which 2018 is a unique year for remediation patterns across these two sectors. In the future we can learn more about the degree to which this pattern holds up.

In the dashboard panels, you can explore these same data for local school systems and schools. For example, the second panel provides a comprehensive view of two and four-year college numbers for all local school systems in 2008.

This is followed by a chart showing results for individual systems over the longer period, 2013-2018. In the case below the filter is selected for Huntsville City Schools.

The fourth panel provides a view of these numbers for all schools in 2018.

The system name filter can be used to see all the schools in a single system. This is shown for the Birmingham City Schools.

Finally, you can drill down to data over time for an individual school. Use the filters to look up systems and schools of interest to you.

Explore on Your Own

The final set of charts shows the remediation rates in math and English for all systems and schools over time.

Turning the Corner: Is Remediation Good or Bad?

A downward trend in the percentage of graduates taking remedial courses is positive. This could mean Alabama is increasing college readiness among students in its public schools, and more of those students attending college are better prepared.

Still, the downward trend in remediation is happening across the nation, and in part, reflects a movement away from using remedial courses in colleges and universities.

College remediation has come under consistent attack from critics over the last couple of decades. Research findings on their effectiveness are mixed with negative and positive results for students.

Some research has found that students taking remedial courses earn more credits and are more likely to graduate than comparable students who did not address fundamental problems through remediation. More commonly, research has found the opposite. Students who could have made progress in their curriculum were held back, lose the will to continue, and their family bears the cost. Financial assistance programs rarely pay for remedial courses. The mixed findings of these studies have fueled ongoing debate, though more rigorous research is now providing a closer look at what might really be happening.

A well designed, highly rigorous study published in 2017 by researchers at Vanderbilt and Harvard found that students who are on the margin would more than likely be better off pursuing regular college courses. Those placed in remedial courses will likely earn fewer credits over time and are less likely to graduate from college. At the same time, students on the lower end of the spectrum who are taking remedial courses will likely fare better in college than comparable students who do not take remedial courses. This was especially true for students taking remedial English.11

These are students who genuinely need a basic foundation in order to make further academic progress. Past research has documented evidence of students enrolling in four-year universities who cannot compose a complete sentence. It does raise questions about the appropriate educational route for students who lack important basic skills, but who would like to attend college. Where would these students best be served?

In response to criticism of remedial education, colleges have moved toward a broader and more complex set of resources for helping students. In this environment, remedial courses are on the lower end of a continuum of resources and strategies designed to support students experiencing challenges. The downward trend in remediation is likely in part due to remediation increasingly not being seen as the preferred alternative for students on the margin of needing assistance. The wider support now found in colleges include:

- Comprehensive learning centers, writing centers, and math centers with mentors and tutors

- Student learning communities

- Peer tutoring and mentoring

- First-year freshman seminar

- Summer bridge program before the fall college term

- Paired courses where students apply basic skills in one course to the content learned in another

- Support in time management, organizational skills, resilience, and self-regulation

Unfortunately, programs vary in their effectiveness. Fewer students in remedial courses do not necessarily mean colleges are achieving higher graduation rates. But some programs are proving effective. Learning communities where students share and learn together have experienced strong success in many cases.

Still, the best medicine is a strong foundation during the pre-school through high school years, combined with strong family support.