New research indicates that lower fines and fees raise more revenue than higher ones, and that a “collections fee” that is supposed to incentivize payment is instead associated with greater debt.

The report, Findings from the Jefferson County Equitable Fines and Fees Project from MDRC, provides insight into an issue the Legislature is struggling to address: Alabama’s patchwork system of fees and court costs. Earlier this year, the Legislature established a Joint Interim Study Commission on Court Costs to examine ways to reform and standardize the court cost system. The Commission will report to the Legislature in its upcoming session early next year.

The new report, a Jefferson County case study, uses five years of case-level data to examine drivers of court debt accumulation over time. PARCA Senior Research Associate Leah Nelson was co-founder and co-principal investigator on the project.

What are fines and fees?

Every year, criminal courts in Alabama assess an unknown amount in fines, fees, court costs, and restitution. Fines are intended as punishment, while fees (including court costs) are meant to cover the expenses associated with the case. Some people are also assessed restitution if the offense they were convicted of resulted in a financial loss to a victim.

Although the total amounts assessed and outstanding across Alabama’s criminal courts are unknown, annual collections are substantial. Criminal courts drew a total of nearly $114 million in 2024 alone, including $6.1 million that remained within the court system, while $80 million was disbursed to non-court entities such as the General Fund, the Alabama Department of Economic and Community Affairs, the State Department of Education, and American Village at Montevallo. And, finally, $12.7 million in restitution was distributed to victims.

Fines are supposed to deter involvement in the criminal justice system, while fees exist to recoup the cost of court involvement, while also generating revenue for the state. New research suggests that higher fines and fees are counterproductive: producing less revenue, creating higher levels of unpaid debt, and prolonging individuals’ involvement with the criminal justice system.

Insights provided by Findings from the Jefferson County Equitable Fines and Fees Project include:

- People assessed lower amounts at the time of sentencing paid more money and were more likely to pay their debt down to zero, as compared to people assessed higher amounts (who typically saw their balances increase over time). In other words, people who were assessed less debt were not only more likely to finish paying, but they paid more money.

- A 30% collection fee assessed when people are 90 days late with their payments resulted in higher unpaid balances and a decreased likelihood of paying off their fines and fees.

- Indigent people were assessed higher financial penalties than their more affluent peers.

- Victims may never receive, or fully receive, financial restitution because of how fines and fees revenue is distributed.

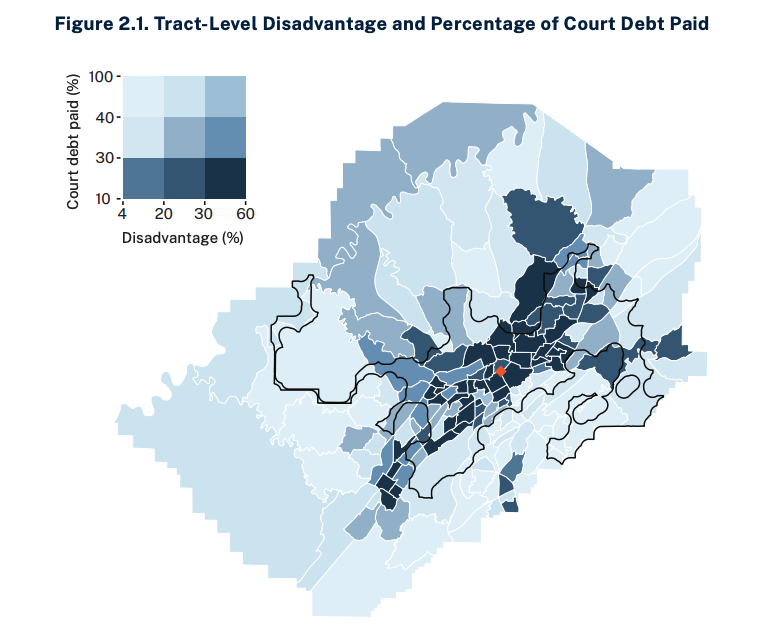

- Court debt was concentrated in census tracts marked by high levels of concentrated disadvantage, a composite metric that measures a given location’s level of socioeconomic challenges.

How does the system work?

Assessment of debt

Fines, fees, and costs are assessed at the time of sentencing in nearly all criminal cases where a person is found guilty. Amounts are set by statute. A typical sentence simply includes a note that the defendant is to pay fines, fees, and costs, along with any restitution that may be due. Judges do not typically say the amount out loud at the time sentencing, so it is common for people to agree to pay as part of a plea without knowing exactly how much they will owe. While judges are required to assess fines and fees, under the Alabama Rules of Criminal Procedure (Rule 26.11), they have broad discretion to set payment plans or even forgive debt if a person is unable to pay. The same rule allows judges to incarcerate people who willfully refuse to pay.

Fines and fees may be the only sanction a person faces in a low-level case. In more serious cases, fines and fees are imposed in addition to supervision or incarceration. Many people who are assessed fines and fees are unable to pay them all at once, and it is common for judges to allow them to pay in installments.

Research shows that Alabama residents who owe fines and fees over long periods of time often make desperate choices as they seek to stay current on their debt. A 2018 survey showed that 83% gave up a basic need like rent, car payments, or medication; 44% took out a payday loan; and 38% percent admitted to engaging in unlawful activity – usually selling drugs, stealing, or sex work – in order to keep up with their court payments.

Even so, half of those surveyed told researchers they had been jailed in connection with unpaid debt. “Every time I turn around, they got a warrant out because I can’t pay,” one man said. “Having to fear the police is not right because of debt.”

Distribution of revenue

Alabama Code sections related to fees name the entity or entities to which revenue collected from fees must be disbursed. However, the order in which money is disbursed falls to the discretion of the Chief Justice of the Alabama Supreme Court. Over the decades, default priorities have been programmed into the State Judicial Information System (SJIS), which is the software used by district and circuit courts to docket and track cases.

Disbursements operate on a “cascade” basis, meaning the top priority entity must be paid in full before the next entity in line gets a single dollar. Under the current default priority system, court costs are paid first, and victims who are owed restitution are paid last. If a person who owes fines and fees falls behind on their payments by more than 90 days, they are automatically assessed a “collections fee” of 30% of what they owe. If assessed, the collections fee becomes the top priority and must be satisfied in full before any other fund receives a share of revenue. Judges have the authority to re-order priorities (for instance, to put restitution at the top of the list), but must issue reprioritization orders on a case-by-case basis.

Findings from the Jefferson County Equitable Fines and Fees (JEFF) Project

Following the money

- The average initial amount assessed in cases included in the JEFF sample was $1,253.52.

- 42% of people pay nothing at all toward their fines and fees.

- People were more likely to pay who were:

- Not indigent

- 50% of non-indigent people paid off their full debt, compared to 16% of people who were represented by public defenders due to low income)

- Facing lower fines

- People in the lowest quartile of court debt assessed (a median debt of $121) tended to pay off their debt. By contrast, people in the top quartile (with a median initial assessment of $1,827) saw their debt nearly double over the five-year period studied.

- Not indigent

- Over 60% of cases in the sample were assessed a 30% collections fee, which is added to the balance when a person fails to pay anything toward their balance for 90 days.

- Collections fees were associated with an average $827 increase in unpaid balances, with only $262 in payments on average after the fee was imposed. Those assessed the fee were less likely to pay off their debt.

In other words, the collection fee, which is intended to increase revenue, is more associated with increased debt.

Geographic Concentration

- Geographically, debt was concentrated in the central valley area of Jefferson County, which is also home to a disproportionate percentage of Jefferson County’s Black residents.

- People who lived in census tracts marked by concentrated disadvantage were much less likely to pay down their debt as compared with people in more affluent areas of the county. A one-percentage-point increase in concentrated disadvantage corresponds with 13% less court debt paid.

The human consequences of fines and fees

Most people (71%) in the sample were defended by a public defender, meaning that a judge determined they were indigent at the time of trial. Unsurprisingly, people who were indigent paid less toward their court debt than those who could afford to hire a lawyer. More surprisingly, JEFF researchers found that across all charges, indigent people were assessed higher financial penalties than their more affluent peers.

In interviews, court practitioners expressed frustration with the system. They described administrative headaches associated with attempting to keep up with debtors who often have unstable housing situations and don’t receive notices reminding them to pay. They felt that the 30% collections fee was deeply problematic, but worried that the district attorney’s office couldn’t operate without the revenue it generates. They expressed a broad desire to see court and law enforcement operations fully funded by the legislative branch, rather than being tasked with generating their own revenue.

Meanwhile, people who owed court debt described feelings of fear. Few were aware that they were allowed to ask for their court debt to be forgiven, and many thought the money was kept by local police or courts. (In fact, most of it flows back to the state.) Discussing the dread associated with owing court debt, one person said, “It’s like drawing an X on your back and I got you forever.”