Only about half the students who earn four-year degrees from Alabama colleges are found to be working in the state five years after graduation, according to a new study by the Alabama Commission on Higher Education.

The study, which compared graduation records to labor force data, found that 62% of in-state students who earned a degree were in the state’s labor force after five years, but only 14% of the out-of-state students who earned bachelor’s degrees from Alabama institutions continued to work in the state.

Keeping more college graduates in Alabama is vital. Increasing the number of highly trained and educated individuals in Alabama is a cornerstone goal of Success Plus, the workforce improvement initiative championed by the Governor’s Office and state business and education groups. So far, most of the attention in that initiative has gone toward enhancing connections between education and business and aligning education and skills offerings with the needs of students and Alabama’s employers. Those efforts may help keep graduates, but more direct retention efforts appear to be warranted.

Education Powers the Economy

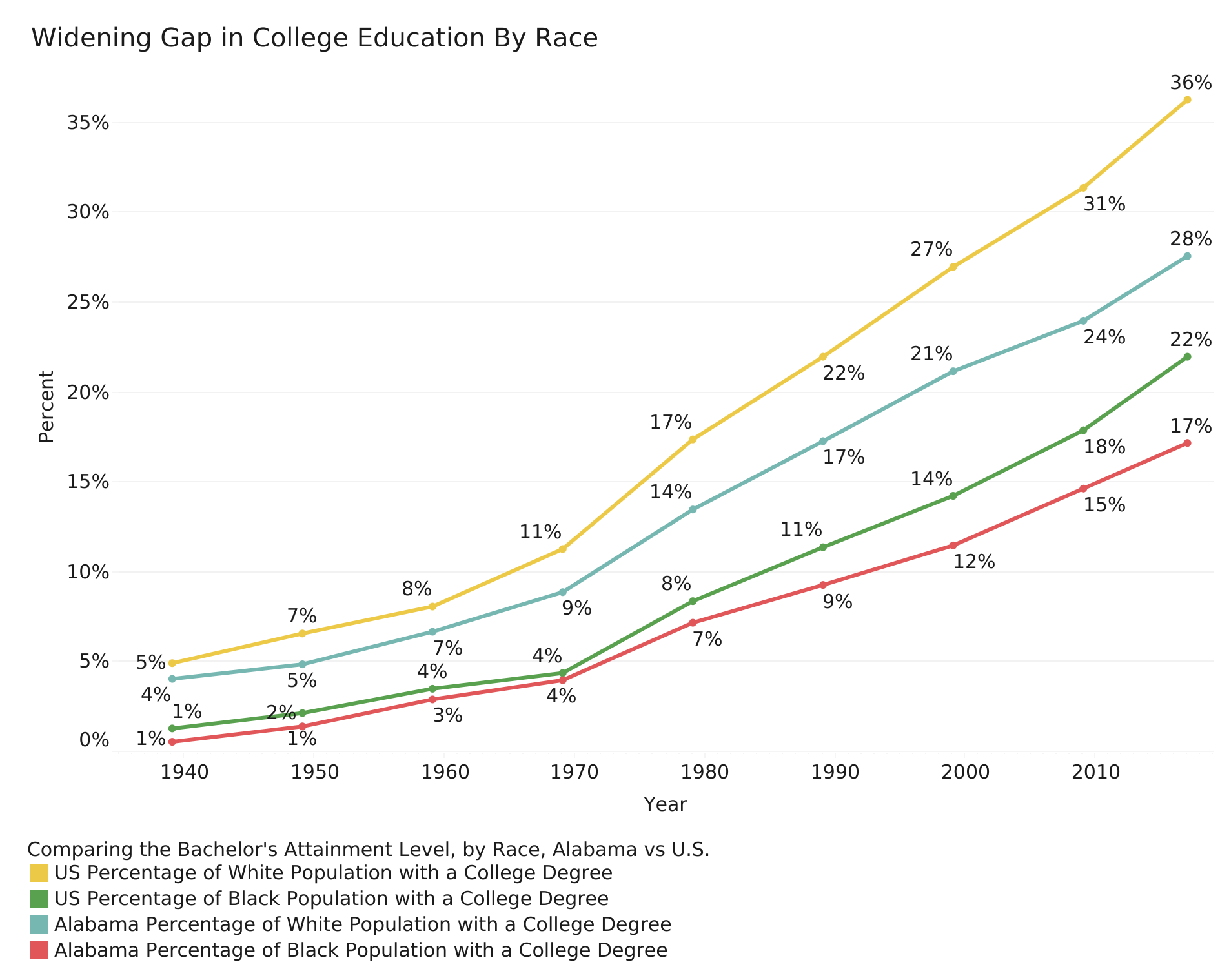

The state’s overall economic and social prosperity is strongly tied to its raising levels of educational attainment. Earning power and labor force participation rates are closely linked with educational attainment, a fact the ACHE study reinforces. As a recent PARCA analysis shows, states with higher levels of education, particularly bachelor’s degree attainment, have higher income levels and better health outcomes. Alabama has historically lagged behind other states’ residents with a high school degree but is now close to the U.S. average. However, when it comes to college education, the gap remains, and may be widening.

Post-high school training and education is required in most of the job fields where employment growth is occurring. Companies looking for highly skilled workers tend to locate and expand in areas where those graduates are concentrating. That drives job creation which then draws applicants, creating a feedback loop.

This cycle can be seen within Alabama with metro cities and counties drawing an increasing share of the highly educated population. And it can be seen nationally, as the percentage of population with a college education grows faster in other states than it is grows in Alabama. The ACHE study shows one reason why: Alabama is exporting its higher education graduates.

ACHE’s study used institutional data from Alabama two-year and four-year schools to identify graduates and then looked for those graduates one year and five years later in Alabama Department of Labor data drawn from the unemployment compensation system.

The study would not capture graduates who are self-employed or who are not in the workforce but are still living in Alabama. And it does not provide information on where graduates may have moved.

Still, ACHE’s analysis is an innovative collaboration between state agencies, a collaboration that previews the insights that can be gleaned from a privacy-protected, linked system of government databases.

- Rate at which graduates are working in the state five years after graduation

- In-state employment rate by degree field and degree level

- Earnings by field and degree level from community college-awarded certificates up to doctoral degree.

National Comparisons

Since this is data specific to Alabama graduates and Alabama workers, ACHE can’t provide a matching dataset from other states to determine whether Alabama’s retention of graduates is higher or lower than other states.

However, studies based on other data also indicate that Alabama is a net exporter of college graduates and is experiencing a brain drain.

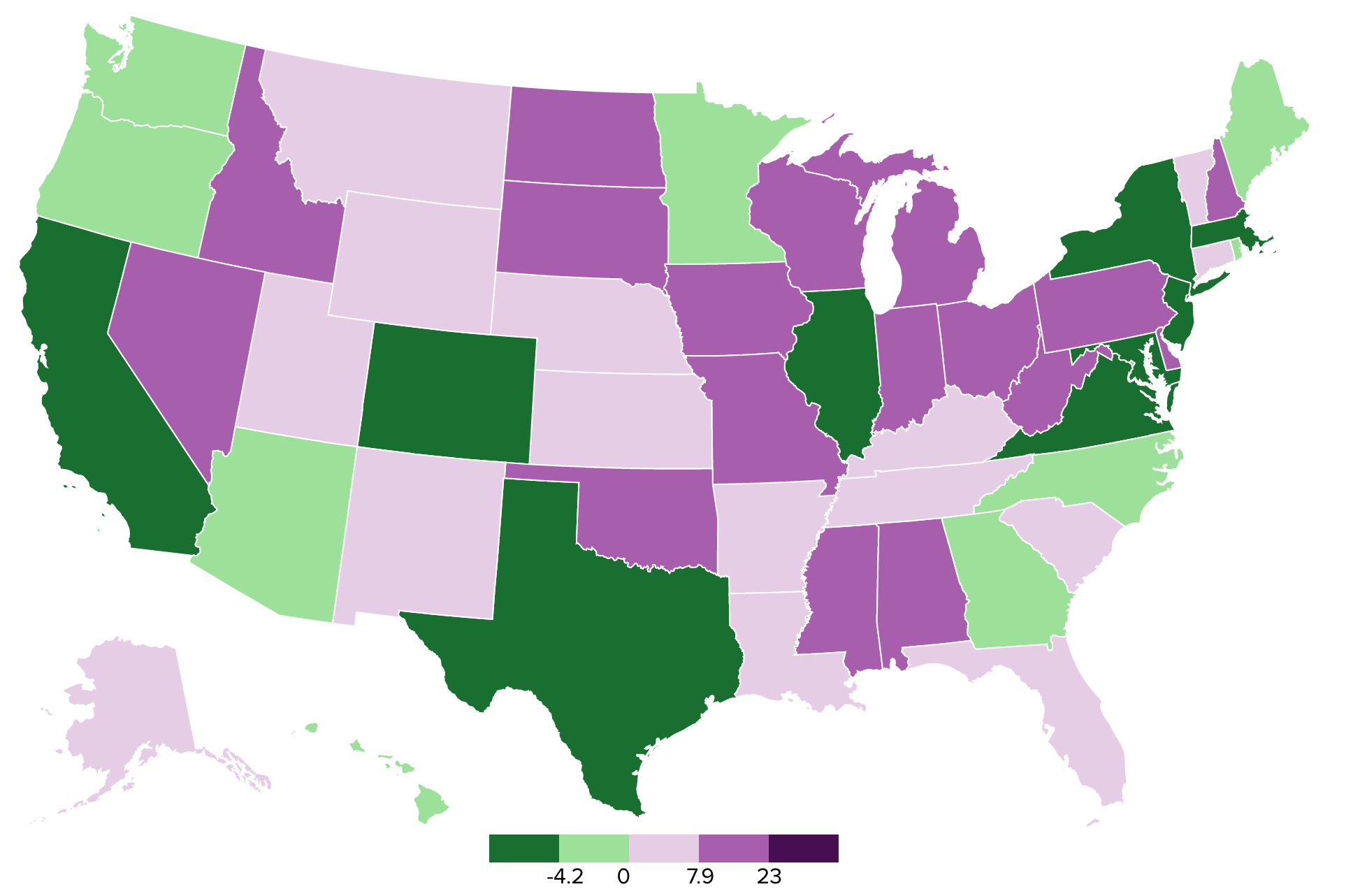

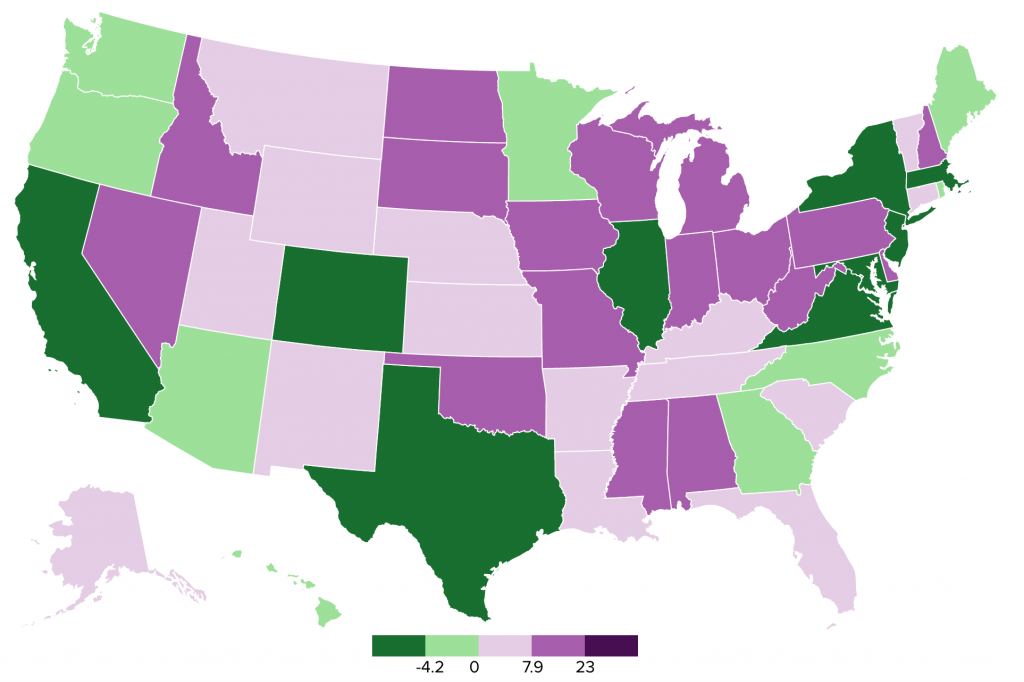

A 2019 study by the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress used Census data to track patterns of migration between states of individuals with higher education credentials.[1] The data identified individuals born in one state who, as middle-aged adults, were living in another state. A group of states clustered along the East and West Coast are drawing a disproportionate share of people with higher levels of educational attainment. Texas, Colorado, and Illinois are also gaining college graduates. They also tend to be home to large cities and their suburbs. The report concludes that the overall pattern of migration has led to a sorting process, a divergence in economic growth, and a parallel divergence in political attitudes between the states.

Figure 1. Net Brain Drain, 2017

This map displays each state’s “net brain drain.” Net brain drain calculates the number of highly educated people who stayed, minus those who left, plus the new highly educated “entrants” who come from other states. Accounting for those flows, Alabama and Mississippi were experiencing brain drain, represented by a positive number. (Alabama has 8.8 percentage point Net Brain Drain; Mississippi’s was 13.5). By contrast, Georgia had a negative brain drain (-1.1), indicating they were actually experiencing a brain gain, drawing in more educated residents than they were losing.

The data from the report indicates that Alabama exports highly educated individuals primarily to other Southern states. Alabama exports the most graduates to Georgia, followed by Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and North Carolina.

Who do we keep?

Most people, 70%, who earned an associate degree in Alabama were working in Alabama five years later. Those earning certificates were slightly less likely to show up on Alabama work rolls five years later, with about 64% located.

For degrees above associate, the higher the degree the less likely that the individual could be found working in the state five years later. Those who earned doctoral research degrees at Alabama institutions are the least likely to be working in the state five years after earning their degree.

Looking under the surface, Alabama residents are much more likely to remain and work in the state compared to non-residents who come to Alabama to attend college.

About a quarter of those earning an undergraduate degree in Alabama originally came from out-of-state to attend college in Alabama. The University of Alabama has been particularly aggressive about recruiting out-of-students. So much so, that resident students now make up less than 40% of the student body. Auburn has a long tradition of attracting out-of-state students, particularly from Georgia, over 40%t of its student body is from out-of-state.

But five years after earning a degree in Alabama relatively few of those out of state students were found to be working in the state.

Graduates in education, health professions, engineering technologies, and social services were most likely to work in Alabama.

On the other hand, doctoral graduates and graduates in fields of study such as architecture, physical sciences, and communications were the least likely to be employed in the state after five years.

As Alabama attempts to raise educational attainment levels in the workforce, those out-of-state students would be a prime target for retention. At the same time, investments in the success of our in-state students are more likely to pay dividends since they are more likely to stay in the state.

Earnings by degree field

The ACHE study confirms national studies on the effect of education on income levels. In general, each step up the educational ladder yields a higher income. That differential further explains why raising educational attainment is advantageous for a state: the more highly educated residents in the state, the higher the total income.

Across the board, a person earning a doctoral degree in a field earns about 3 times more that someone who earned an associate degree in the same field.

This snapshot of earnings does not take into account the cost incurred by an individual who pursued higher education. Nor does it take into account the delay in starting a career while pursuing a degree. However, considering the long term pay off, the additional investment does, on average, produce rewards.

Still, the differential provided by a degree very much depends on which field the degree is in. For instance, associate degree holders in science technologies, construction trades, agriculture, and precision production were, on average, earning over $50,000 a year five years after graduation. On the other hand, bachelor’s degree holders in 23 fields identified in the ACHE study– area and ethnic studies, communications technologies, English, public administration, visual and performing arts, psychology, and foreign languages among them) average less than $50,000 a year after five years.

The highest average salaries among bachelor’s degree holders five years after graduation were among those with degrees in engineering ($74,191) and computer and information sciences ($65,792). Followed by engineering technologies ($59,796), health professions ($54,832), and business management and marketing $54,547).

Strategies for Retention

As a result of the Employment Outcomes report, ACHE has begun to implement initiatives designed to improve the retention of recent graduates. Such initiatives include increasing student engagement with Alabama industry by increasing internships, and having invitation-only community-based job fairs for soon-to-be graduates in certain fields.

ACHE plans to conduct a survey of soon-to-be graduates to get a baseline impression of Alabama and career opportunities. Institutional level results from the Employment Outcomes report have been supplied to colleges so those schools can examine in-state demand for graduates by field. They can also target for retention those students in fields where graduates are being lost.

ACHE is helping retain education graduates through incentive programs that help students pay back college loans in exchange for teaching in high need fields and in school systems that face challenges in hiring teachers. ACHE has also helped local communities, most recently Decatur and Demopolis, with initiatives designed to recruit and retain recent college graduates.

[1] U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee, Social Capital Project. “Losing Our Minds: Brain Drain across US States.” Report prepared by the Chairman’s staff, 116th Cong., 1st Sess. (April 2019), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/4/losing-our-minds-brain-drain-across-the-united-states.