Alabama schools are set to re-open in August, with plans for local systems to offer educational services through traditional on-campus schools, remote on-line education, and a hybrid of traditional and remote learning options.

With the novel Coronavirus still spreading, all plans are subject to change. Already, the state’s largest system, Mobile County, and the Selma City School System have decided not to open school buildings and to proceed with only remote learning for all of its students this fall.

As policymakers, educators, and parents prepare for what will likely be a most unusual school year—including the possibility of additional shutdowns— PARCA gathered information from local reports and two major national polls that attempt to describe what parents and students experienced during the school closures this spring. As schools plan for the fall, these experiences are important to understand.

According to the polls, parents worried the online school experience was resulting in:

- learning loss and lack of academic advancement

- a lack of social interaction for students, negatively impacting student mental health

- inadequate contact between parents and teachers

- a mismatch between the resources provided by schools and the aid parents most needed

- increased inequities in the educational experience

The Shutdown

As COVID-19 spread this spring, schools across the country closed. By March 20, 45 states had closed all schools. By early May, the number climbed to 48 states and the District of Columbia—affecting more than 55 million students. Only Montana and Wyoming allowed schools to remain open, although some systems in those states did close. 1

Almost overnight, schools entered uncharted waters. States, systems, and local schools mobilized resources for parents and students and reimagined teacher-student interaction. For most schools, this entailed some version of virtual education.

According to a Gallop Survey conducted in March 2020, 70% of parents of K-12 students not in school at that time reported their child was participating in an online education program run by his or her school. The survey found that among parents whose children were not enrolled in a formal online education program, 52% were homeschooling with their own materials, 25% were using a free online learning program not associated with their child’s school, and 35% were not engaged in any formal education. 2

Some schools had the capacity to respond to COVID-19 closures comparatively easily. That includes schools in Alabama and elsewhere that were already designed as virtual schools. Other systems in other parts of the country are more experienced in online education because of long winter breaks with harsh weather. Conversely, most schools, educators, parents, and students were thrust into a new learning environment for which they were little prepared.

Parents and students around Alabama reported a wide variance in student experiences, varying according to system, school, grade, and teacher. Some reported students having more work than before the shutdown and spending hours each day with regular virtual check-ins. Others reported that work was considered optional or that students finished nine-weeks of work in just a few days. The long-term effects of the academic transition and the inconsistency of students’ experience will take time to assess.

Parent Reactions

The national nonprofit educational organization Learning Heroes conducted a survey of parents in April and March 2020. The survey, which reached 3,645 parents from across the nation, was conducted in conjunction with the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO), National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS), and the National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE).

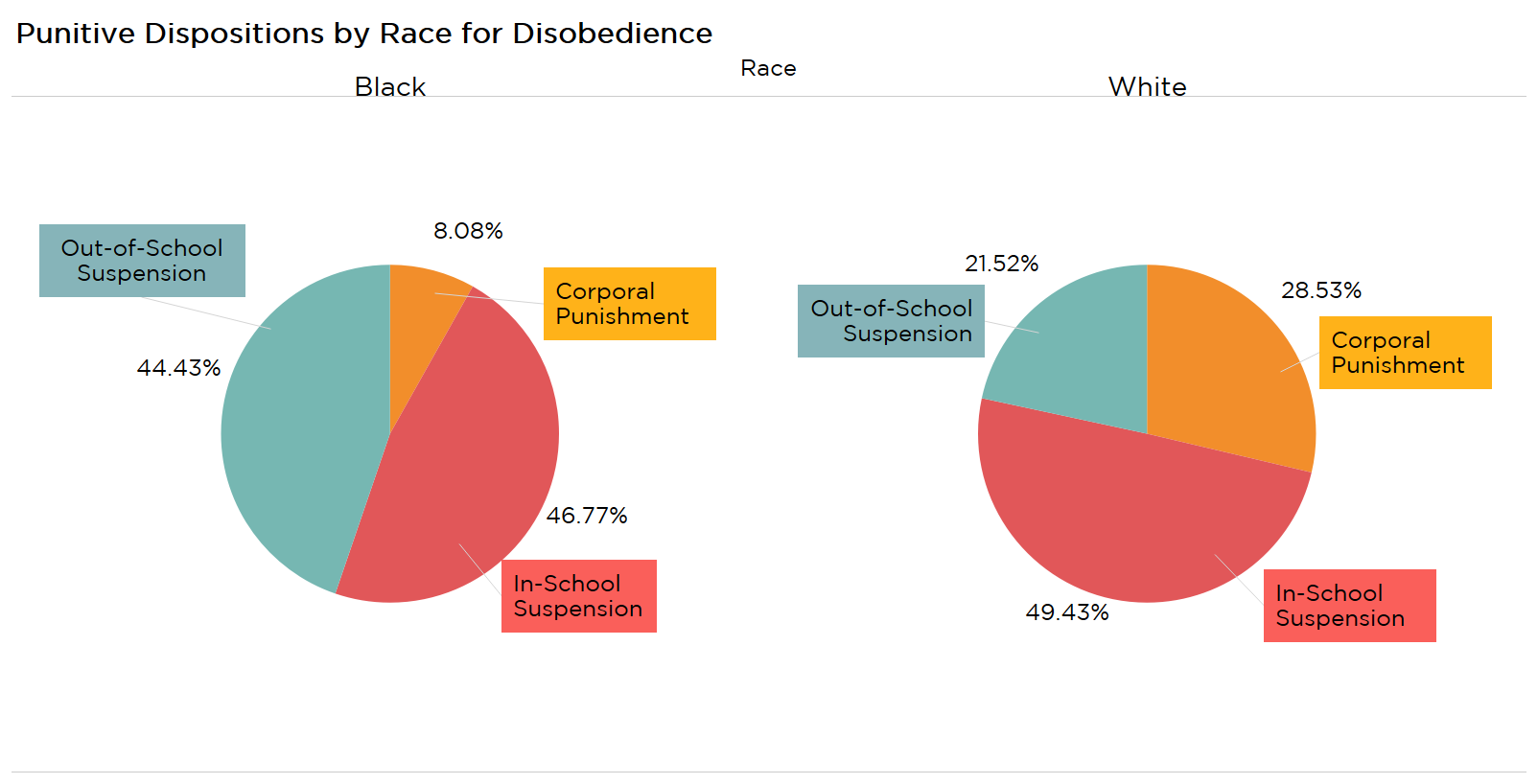

Results show that parents, now in the role of educators or critical partners in their child’s learning, have gained a new appreciation for what teachers and schools do. 3

Figure 1

Some parents reported being overwhelmed, while others reported more involvement in their child’s learning has given them a healthy sense of engagement and better insight on how to help their children learn. These parents look forward to being more involved in schools and their child’s education once schools re-open.

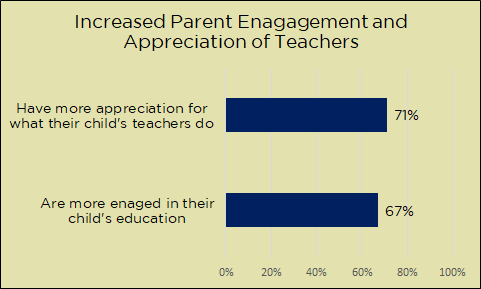

Academic Concerns – Loss of Learning Assessed

Seventy percent of parents expressed concern about the loss of learning and how this will be made up. Fifty-four percent are concerned their children will not be ready for the upcoming school year. These issues raise more fundamental questions about the nature of teaching and learning. High-quality teaching and learning can presumably occur in different forms. With state testing postponed, measuring the impact on student learning gain or loss will be complicated but is an important objective.

Figure 2

States such as California and South Carolina are planning to implement new tools for assessing learning loss. Quick, real-time assessments conducted by teachers in the classroom, or virtually, will likely be most effective. Assessments that take time to report results will have limited utility for teachers but may be instructive for administrators and researchers.

Researchers have tried to predict the magnitude of pandemic-related learning loss by analyzing normal summer learning loss — the degree of academic regression between the end of one school year and the beginning of the next – and treating the COVID shutdown as an extended summer. Some researchers estimate that students likely ended the school year with only 40% to 60% of learning gains achieved during a typical school year. [efn-note] M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., and Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Edworking Papers, May 2020. Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University [/efn_note] Other studies estimated much lower losses. 4 5 6

Some experts believe the projected learning loss is over estimated.

They note that estimates using summer loss as a baseline are not taking into account the learning that occurred through virtual forums and support provided by schools this past spring. Likewise, most of the content students were expected to learn was already introduced to students by March, although students did not have an opportunity in class to practice skills, and develop mastery. Furthermore, teachers are prepared to work with students coming back at different levels of preparation after the summer break, so they will not be caught off-guard. At the same time, this will likely be much more challenging and will be taxing for teachers who are less prepared and motivated to work with diverse learners.

These same experts, however, are alarmed about the challenges facing beginning readers, who usually need continued re-enforcement throughout the year. This could affect future literacy rates and have implications for implementing Alabama’s Literacy Act in the lower grades. 7

Social and Mental Health Concerns

Parents expressed fear about the impact of COVID-19 on their children’s social-emotional well-being, and 59% worry about the impact of reduced social interactions. For young children in unsettled or abusive home environments, the school can be a safe place. Long-term absence from this safe place can become a source of heightened trauma with long term consequences.

Many children may be coping well, but medical experts are concerned about the stress and trauma children (and adults) are experiencing during the pandemic, especially those with underlying mental health conditions. School-aged children experienced sudden changes in their educational setting and routines. Many experienced shock. Some families have had the stress of sickness and death in their families as a result of the virus – though overall a relatively small percentage. Many more families are under financial strain. Concerns have been raised about abuse, neglect, loneliness, and isolation. The virus has affected every facet of the life of children and adults. 8

Symptoms of trauma in school-aged children can include:

| Physical Symptoms | Over-or under-reacting to stimuli (physical contact, doors slamming, sirens) Increased activity level (fidgeting) Withdrawal from other people and activities |

| Cognitive | Recreating the traumatic event (e.g., repeatedly talking about or “playing out” the event) or avoiding topics that serve as reminders Difficulties with attention Worry and fear about safety of self and others Disconnected from surroundings, “spacing out” |

| Social-Emotional | Rapid changes in heightened emotions (e.g., extremely sad to angry) Difficulties with controlling emotions angry outbursts, aggression, increased distress) Emotional numbness, isolation, and detachment |

| Language and Communication | Language development delays and challenges Difficulties with expressive (e.g., expressing thoughts and feelings) and receptive language (e.g., understanding nonverbal cues) Difficulties with nonverbal communication (e.g., eye contact) Use of hurtful language (e.g., to keep others at a distance) |

| Learning | Absenteeism and changes in academic performance/engagement Difficulties listening and concentrating during instruction Difficulties with memory 9 |

Parents can reduce the risk of stress by creating a calm, safe, and predictable environment, communicating and building a positive-supportive relationship with their children, and encouraging their children to develop self-regulation skills.

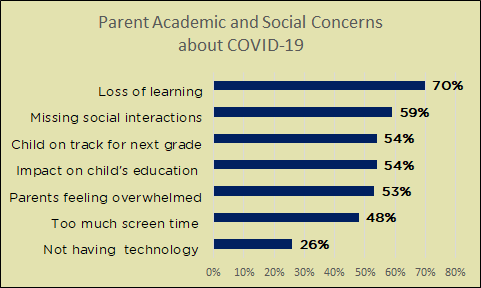

Teacher Interaction

Parents expressed concern about the lack of regular ongoing contact they and their children have with their children’s teacher(s). This is perhaps less critical for self-motivated students with highly resourceful parents or guardians with time devoted to learning at home. But many students depend on regular high-level teacher interaction. Parents indeed may have the will and skill to perform in this role but are working in fulltime jobs. Others express concern about not having the background to adequately support their children. Still, others may be in stressful life situations that rob them of the motivation and energy to serve in this role. In each of these situations more ongoing contact with teachers and community support specialists would likely make a significant difference.

Figure 3

Though parents find communication with teachers extremely helpful, the majority did not receive this support on an ongoing basis. Teachers have found themselves in uncharted territory for which they were not prepared. They too may not have the skills and background needed for online teaching and tutoring. The awkwardness of online communication and technical hiccups can generate additional frustration. Everyone is learning and adapting.

Resources Provided by the School

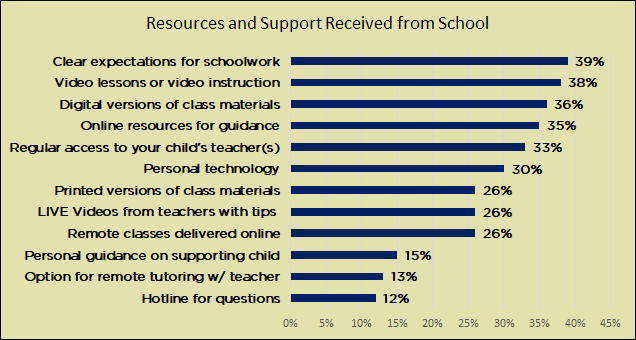

An especially important issue for schools this past spring was providing guidance and resources to parents to assist them in working with their children. The figure below shows the percent of parents indicating they received key resources from their child’s school during the pandemic this past Spring.

Figure 4

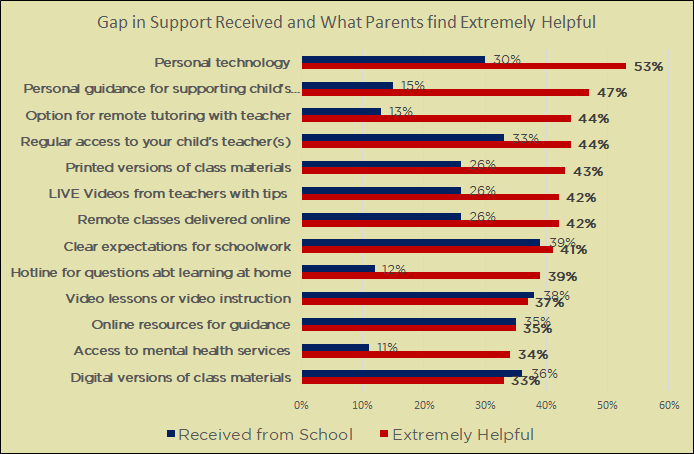

But sometimes what parents received was not what they needed or found most useful. In Figure 5 below, resources are ordered by the percent of parents who found the assistance useful (red bar), from highest to lowest, and the percent receiving the guidance or resource.

Figure 5

The most useful assistance included:

- school provided personal technology

- online guidance

- one-to-one tutoring with teachers

- ongoing regular contact with teachers

- printed versions of class materials

- remote classes delivered online

Parents found printed materials more helpful than digital materials.

The gap between what was offered and what was found most useful, when offered, was largest for the following:

- personal guidance in supporting your child’s learning at home

- remote one-to-one tutoring by teachers

- school provided technology

- access to mental health services

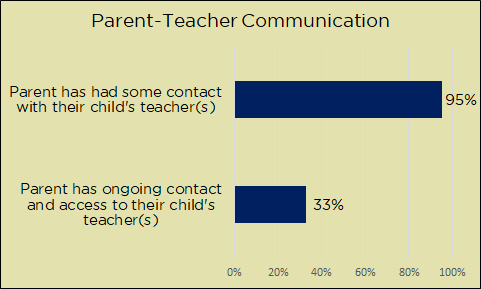

COVID-19 and Equity

A number of observers have focused attention on the profound inequities in education magnified by COVID-19. Systems vary in funding, resources, curriculum, extracurricular offering, teacher experience and in many other ways. These disparities are likely exacerbated when the home becomes, not by choice, the primary learning environment for all students.

Virtual education has the potential for system-by-system and house-by-house differences in capacity to compound each other.

Differences in capacity across households include the following:

- Income and educational attainment of parents.

- The knowledge and experience of parents, guardians, or other adults.

- The time and availability of parents, guardians, or other adults to actively facilitate or assist in their children’s learning.

- Family structure: One and two-parent families where responsibilities are shared.

- Relationships between parent-child, parent-teacher, and student-teacher.

- Access to communication, guidance, and support from teachers and schools.

- Access to community supports and enrichment.

- Access to computer technology and high-speed internet. Capacity and motivation to make use of these resources.

- Access to nutritional food daily.

These obstacles may be greater, but in no way limited, to lower-income areas.

The general public and government leaders most frequently cite a child’s school and teachers as the primary difference in their education. But research has long noted that children do not enter school as a blank slate, and that inequalities begin at birth as a result of different prenatal conditions, and too often are made worse during those early years before school. Children enter school with vastly different levels of preparation. The achievement gap, from this point of view, is a symptom of broader inequality, past and present. Improving education on campus and on-line and building a solid workforce calls for addressing these inequalities in the home and school. 10 Strauss, V. (2020). How COVID-19 has laid bare the vast inequities in U.S. public education. The Washington Post, April 14, 2020. /efn_note]