High school seniors and recent graduates are preparing to enter a workforce that has been disrupted, hopefully only temporarily. In a matter of weeks, the nation has gone from record low unemployment to levels not seen since the Depression. Employers are adapting to a new set of work conditions and the demand for new skills appropriate for remote work is rapidly rising.

The WorkKeys Assessment may now be more valuable than ever in helping employers assess the practical skills and adaptability of potential hires.

WorkKeys Assessments in Alabama

WorkKeys is a standardized test given to 12th graders in Alabama public schools. The assessment is meant to measure skills relevant to many of today’s work environments. This is a test that generates positive results in Alabama with steady progress.

WorkKeys is one of the measures through which a student can be designated as College and Career Ready in the state. They may not have the specialized training needed for particular occupations, but if a student earns a certification at the higher levels, the measure should increase the confidence of employers in hiring staff who are adept at applying useful cognitive skills and knowledge to applied work tasks in contemporary work settings.

The Assessments. The assessments consist of three tests of applied cognitive skills which are relevant, according to ACT’s research, to over 20,000 occupations:

- The Applied Math test

- The Graphic Literacy test

- The Workplace Documents test (applied reading for understanding)

Students are awarded a National Career Readiness Certification if they score a Platinum, Gold, Silver, or Bronze score on the WorkKeys. Platinum is the highest level, followed by Gold, Silver and Bronze.

After modifications to the 2018 assessment created significant fluctuation among the different certificate levels, the results in 2019 showed steady gains in the Platinum and Silver levels, and slight decreases in the percent of students earning Gold and Bronze certificates, as well as the percent of students not receiving any certificate.

In Alabama students earning a Silver certificate or above are considered career ready.

Highlights of the WorkKeys test results for the Class of 2019 include:

- 66% of Alabama high school graduates were

deemed workforce ready as measured by the ACT WorkKeys assessment, an improvement over 64 % in 2018.

- At 94%, Hartselle had the highest percentage of workforce-

ready

- The Silver Certificate continues to be the level with the highest percentage of students.

WorkKeys is emerging as another source of information for making employment decisions and helping prospective workers learn about strengths and weaknesses and opportunities for growth. Using job profiling data provided by ACT, the Alabama Department of Labor maintains data listing the median WorkKeys scores for high demand occupations requiring an associate’s degree or less.

2019 Assessment Results

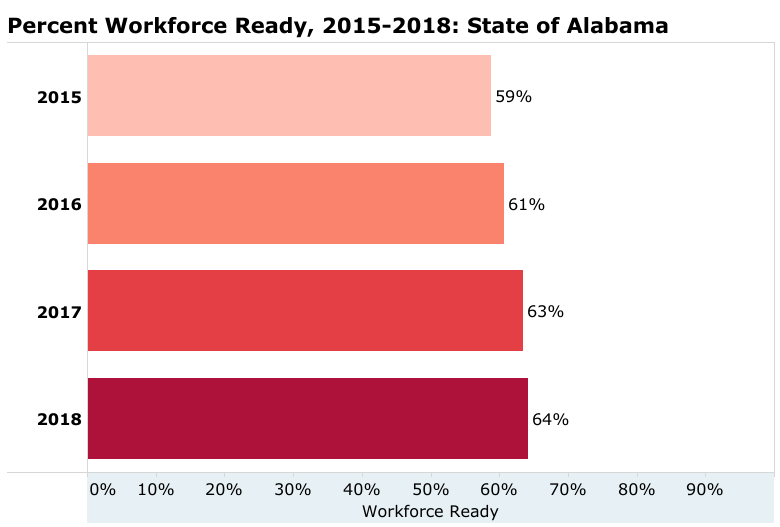

The following charts show the percentage of graduates in Alabama who demonstrated workforce readiness on WorkKeys assessments.

In 2019, 66% of high school graduates taking the assessment were deemed workforce ready. This percent has steadily increased since 2015.

Workforce Ready at the Local Level

The following charts focus on workforce readiness among graduates at the local level. A county view is appropriate when thinking about the quality of a local workforce.

Of course, local school systems and schools are the places where students develop knowledge and skills related to work readiness.

Listed below are the top ranked systems based on workforce readiness assessed through WorkKeys:

- Mountain Brook City – 95%

- Arab City – 94%

- Satsuma City – 94%

- Cullman City – 89%

- Hartselle City – 87%

- Trussville City – 87%

- Homewood City – 86%

- Madison City – 86%

- Brewton City – 85%

- Guntersville City – 85%

Mountain Brook has made positive gains over the past two years and appears to remain committed to WorkKeys as a valuable assessment.

With committed effort, WorkKeys is an assessment where systems can show growth, as demonstrated by a variety of systems and schools in Alabama.

A number of large and medium-sized systems made noteworthy gains over 2018. Auburn City topped all, showing remarkable gain (up by 24 percentage points).

Among the schools, Loveless Academy continued its top ranking with 100% of students deemed workforce ready. Top schools include:

- Loveless Academic Magnet High School, Montgomery County – 100%

- New Century Technology Magnet High School, Huntsville City – 95%

- Mountain Brook High school – 95%

- Brewbaker Technology Magnet High School, Montgomery County – 94%

- Arab City High School – 94%

- Ramsay High School, Birmingham City Schools – 94%

- Satsuma High School, Satsuma City Schools – 94%

A number of large and moderate sized high schools experienced positive gain over 2018. This is an area of growth for a number of schools failing to show gains in more purely academic assessments.

Change in Certificate Levels

Students are deemed workforce ready if they achieve certification at the Platinum, Gold, or Silver levels. The charts show that the percentage of students at the Gold and Silver levels increased moderately from 2015 through 2017, with Platinum barely making a dent. After modifications to one of the tests in 2018, Gold and Platinum level certificates grew substantially, while Silver certificates dropped significantly. The percent at each level in 2019 is comparable to 2018, but with positive gains in Platinum and Silver. The percent of students at the lowest level, with no certificate, continues to drop.

Overall, this resulted in a higher percent workforce ready for the state, with a positive trend toward higher certification levels.

Change in Certificate Levels at the System Level

Platinum: Mountain Brook and Homewood City finished in a tie with the highest percent of Platinums, followed by Madison City, Hoover, Hartselle and Arab City. Aburn City climbed up in 2019 to join these state leaders.

Gold: Oneonta, Arab, and Mountain Brook are the systems with the highest percentage Gold. Though the majority of systems decreased at the Gold level, a number of systems increased their percentage. Leading the way in percentage point gain was Chickasaw City and Jacksonville City, followed by Piedmont City and Talladega County. Arab City continues to show nice gains as well.

Silver: This is the minimum level to be counted as workready. A number of less affluent systems are among the leading systems for Silver certificates. Systems with the highest percentage at this level include Opp City, Satsuma City, Haleyville City, and Lamar County. The vast majority of systems increased in the percentage of students earning Silver certificates in 2019, led by Opp City.

Subgroup Analysis

Analysis of subgroup results shows a continuing disparity between subgroups. Use the filters to see how systems differ in subgroup performance. Some schools may be better at assisting struggling groups than others.

The highest performing groups include students who are Asian, white, non-poverty, female, and military-affiliated. The lowest-performing groups are black, migrant, and special education. While all of the racial groups are increasing their percentage of workforce ready, black students have made the most gain since 2015.

Females continue to outperform male students, though both have shown comparable positive growth since 2015.

In looking at trends, all racial groups are showing progress from year to year, especially Asian and black students.

Finally, special populations are also showing positive growth in workforce readiness, especially students qualifying for free lunch (poverty) and students living in foster homes.

Discussion

The 2020 report, Education Matters, written by PARCA on behalf of the Business Education Alliance, recommends increasing the awareness of WorkKeys as a valuable tool for employers, communities, and schools.

In addition to the assessments, WorkKeys provides a full suite of resources that can help provide training for teachers, test preparation for students, and design career-related curricula to help students improve their “hard” and “soft” skill levels. ACT Career Ready 101 is designed to help teachers bring work readiness skills into the classroom. This raises questions about how students become workforce ready in school. Beyond special resources for preparation, is the curriculum and content delivered in schools changing to strengthen career readiness, even in traditional academic subjects?

The long-term future of WorkKeys will be determined by the continuing value educators give to these assessments and suite of resources, and the degree to which employers value WorkKeys. A growing number of communities and employers are aware of the utility of WorkKeys, but this still varies across the state. Currently, schools also vary in the degree to which they emphasize WorkKeys.