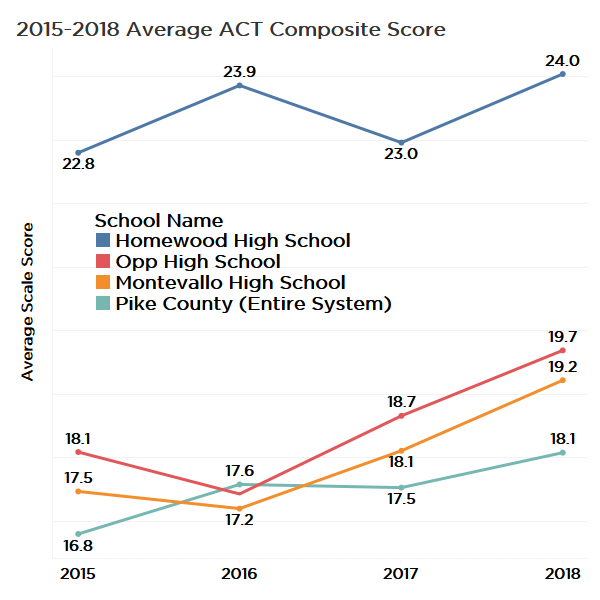

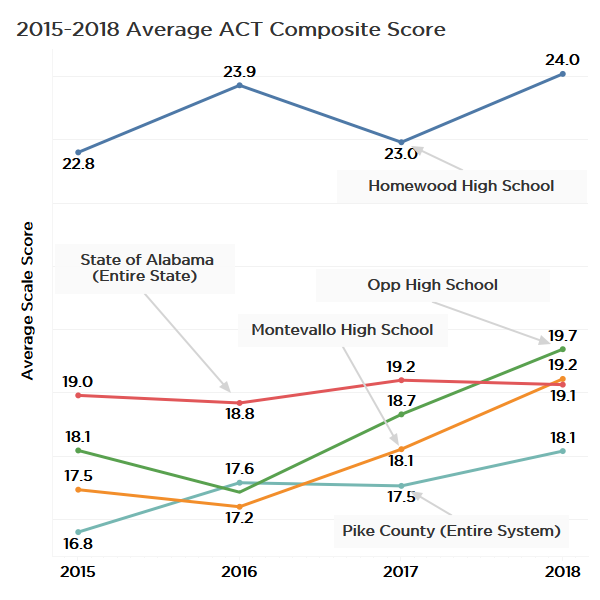

After publishing ACT results for the graduating Class of 2018, PARCA contacted several of the schools and systems in Alabama that showed the largest improvement in average composite ACT scores between 2015 and 2018. PARCA wanted to know what, if anything, the schools did, either specifically for the ACT or in general, to improve students’ college readiness levels.

We received responses from the Pike County School System, from Montevallo High School, Opp High School, and Homewood High School and System.

The schools are across the spectrum when it comes to the economic composition of the student body. Using the percentage of students qualifying for a free school lunch as a measure of economic disadvantage, Homewood (20 percent) and Opp (41 percent) have lower levels of economic disadvantage than the state average (46 percent). Meanwhile, Montevallo High School (54 percent) and the Pike County School System (73 percent) have a higher percentage of disadvantaged students than the state at large. In terms of per-pupil spending, Homewood and Pike County are in the top 20 in per-student funding, while Opp and Shelby County are closer to, but still above, the state average.

Statewide, the average composite score has been basically flat since 2015, rising from 19 to 19.1 in 2018. That tenth-of-a-point gain statewide contrasts with improvements at the responding schools of between 1.2 and 1.7 points on a 36-point scale.

In response to PARCA’s query, school officials described the factors that they believe led to improvement. These are only observations and no underlying studies were performed to prove a cause and effect. However, the approaches described, while not uniform, had common characteristics that have been shown by educational research to lead to improved student performance.

Common Approaches

While the details varied amongst the responding schools, the common themes would not come as a surprise to anyone familiar with education research:

- Setting high expectations for all students.

- Focusing on the delivery of strategic, high quality, standards-based instruction, not teaching the test.

- Monitoring of student progress, providing aid for students who struggle and resources for students who want an additional challenge.

- Teaching students to a level of depth expected at the college level, a level that goes deeper than recalling facts.

- Emphasizing to students the importance of the ACT and providing access to ACT preparation materials and courses.

Critical Thinking Skills

While all four respondents, to varying degrees, provided targeted preparation for the ACT itself, all emphasized that the real foundation for success was an across the board dedication to a robust standards-based approach to instruction, an approach that challenged students to think beyond surface level of recall of facts, dates, and formulas, and to develop a depth of knowledge and the ability to apply what they learned.

Engaged Faculty

All four viewed the adoption of the Alabama College and Career Ready Standards, standards that included input from the nationally-aligned Common Core standards, were a positive development. The adoption of the new standards provided each system an opportunity to engage faculty in a deep review of what should be taught at each grade level and whether the school curriculum was aligned with the standards. Professional development was provided to ensure teachers were prepared to deliver the content and level of depth called for in the standards.

College-Level Courses

Both Homewood and Opp pointed to the high quality of Advanced Placement (AP) courses. Both systems have added courses and increased access to AP, which are college-level classes delivered in high school. School officials said the high-quality course content and the training teachers receive in order to teach AP classes results into a richer experience for students. That experience prepares them for the more complex level of thinking required to perform well on the ACT. The ACT is, after all, a test that seeks to measure student readiness for college-level work, and AP courses are designed to reflect college-level learning. Homewood emphasized that AP classes at Homewood are open-enrollment rather than selective. Their enrollment continues to grow, as do success rates on the AP test.

Pike County has adopted a different strategy for exposing students to college-level coursework: send them to college. Pike County will have 24 seniors graduating this year with over 60 hours of college credit earned at Troy University or through community college programs. That means those students enroll with enough credit to have earned an associate degree and plenty of experience with college-level work. Beyond the quantifiable results produced for students, the system is spending more efficiently, according to Pike County Superintendent Mark Bazzell. In a small school system, it is difficult to generate the numbers of students participating in AP offerings to justify the investment, especially when college-level courses are already available in the community at the local colleges. Because some national ranking systems look at AP participation as a marker of quality sometimes Pike County receives lower rankings than it deserves considering the opportunities it provides students through the dual enrollment option.

Below are observations from each school or system.

Pike County System

The Pike County School System continues to exceed expectations and draw attention with its attitude of high expectations, no excuses, and its methodical and creative approach to improving outcomes for students. Pike County has been featured in two Business Education Alliance (BEA) reports, Exceeding Expectations (2016) for exceptional performance on the ACT Aspire and in Leadership Matters (2018) for the system’s innovative approaches to improving college and career readiness. PARCA authored those reports, with support and consultation from A+ Education Partnership.

Pike County’s superintendent began the path to the current level of success more a decade ago. When he took over as superintendent, he began a campaign to build a faculty that uniformly believed that all children were capable of high performance. The second step was helping the faculty understand what students needed to know according to the national standards and providing teachers with the training in how to effectively teach those standards.

Bazzell found ACT Aspire, ACT’s suite of standardized tests for elementary and middle school students, to be a valuable tool for accessing student progress. The State used Aspire as its standardized test for accountability purposes but dropped it before the 2018 school year. Pike County now pays on its own for Aspire and uses data from the test to inform instruction. Continuing to use the Aspire exposes Pike County students early and often to ACT-designed standardized test, a test that predicts achievement levels on the actual ACT college readiness test.

Considering its level of student economic disadvantage, Pike County now generates consistent high performance. Bazzell provided the most detail on specific ACT preparation measures the two high schools in the system have adopted.

- Encouraged students to start taking ACT earlier (9th grade)

- Increased awareness of the importance of ACT through posters in the hallway, data analysis with students, parent meetings, etc.

- Teachers’ use of bell ringers (quick questions to open class) that are aligned with ACT questions

- Implemented Saturday ACT study sessions with content-area teachers

- Utilized a Discovery Block (time set aside during day) for ACT and PreACT practice, with a schedule that rotated by content area

- Utilized actcademy.org to create individual study paths based on a student’s PreACT score.

- Encouraged students to put various ACT prep Apps on their phones and use them during free time at school and at home

- Included ACT prep materials into a Southern Research Education Board-designed college readiness course, which is now mandatory for students who score lower than a 19 on the ACT

- Assembled a list of online resources student can use to prepare for the ACT

Montevallo High School, Shelby County System

Montevallo High School Principal Brandon Turner, who arrived at Montevallo in 2015, emphasized that his faculty and staff function as a team. Learning targets are set by subject and grade level and formative assessments are administered to track student progress toward the targets.

Turner said a central emphasis for the school is improving instruction and adding depth of knowledge. There is a concept in education called the four levels of knowledge. The first is simple recall, the second level is connecting facts together as concepts or patterns. The third level, strategic thinking, applies concepts learned to novel situations, and the fourth level of knowledge is demonstrating the ability to draw from multiple sources to identify problems and construct solutions.

Questions on the ACT often go beyond recall, simple connections between points of data, and challenge students to think about the bigger picture.

“The depth of knowledge has to be embedded in all your classes,” Turner said. “If we aren’t practicing those things, they won’t succeed.”

Montevallo also offers a guided practice period during lunch that juniors are able to take advantage of, and the week before the administration of the ACT, all the junior classes focus on preparing for the test.

Opp High School, Opp City System

Standards and Active Learning

When Alabama adopted new learning standards, the Opp City System made a systemwide concerted effort to support teachers in understanding and teaching the standards. And it paid off. Opp was featured in 2016’s Exceeding Expectations report for showing the most improvement in math on the ACT Aspire.

Principal Aaron Hightower said the high school continues to focus on teaching that is grounded in learning standards and objectives but is also challenging teachers to innovate in how they teach in order to keep students engaged. For example, teachers at Opp Hike School are encouraged to compress lectures into the first 20 minutes of class and assign group projects to work on for the remainder of the period.

Faculty collaboration

The faculty coordinates across grade level so each grade level subject matter team builds on what has been taught in the previous year and prepares students for the next year.

Course Rigor

For Opp, AP courses have been especially beneficial in increasing the rigor and quality of courses. And, according to Hightower, all courses are supposed to challenge students to think beyond surface level learning.

Diagnostic Tools

To make sure all students stay on pace, Opp uses a diagnostic tool called Edmentum, which measures student skill level and identifies specific areas of weaknesses that need to be addressed. For struggling students, it then prescribes a personalized learning plan to address those weaknesses.

ACT Specific Preparation and Incentives

Opp started offering the PreACT to 10th graders the year before the State made it a requirement. That has allowed students to build familiarity with the kinds of questions the ACT asks.

And finally, to encourage all kids to put in the effort on the ACT, Opp offers incentives. If a student can document a two-point gain on the ACT, they qualify for a school trip to the new water park in Baldwin County.

“Now that creates a buzz,” Hightower said.

Homewood High School, Homewood City System

Instructional Leadership

As with the other responding schools and systems, Homewood school officials first pointed back to the fundamentals of preparation that put students in a position to succeed. Patrick Chappell, the system’s director of instructional support, pointed to the academic focus created in the system by each school in the system having an assistant principal for instruction. Those principals regularly meet with each other and with their faculties during embedded professional learning time to ensure educational continuity classroom to classroom.

Learning Targets

The system has teacher-developed learning targets for students, by grade and by subject. Those targets reflect but often exceed the state’s Alabama College and Career Ready Standards. Despite this tight definition of intended outcomes for students, Chappell said, teachers and students are given latitude on the style and pace of learning. They are not bound by pacing guides, for example. The emphasis is on mastery of standards, not flying through every bit of material.

AP Courses

Homewood offers an array of AP classes and, in recent years, has seen a continuing rise in the number of students and the percentage of students choosing to take those courses.

Teachers have received additional professional development to prepare for teaching AP classes, and the system also pays for students to take AP exams.

Access to AP classes is not restricted by GPA or participation in an “honors” program. Any student who wants the rigor and challenge of a college-level course can take AP classes. Even with the rising participation levels, the percentage of students earning a successful score on the AP exams continues to climb as well. With more students succeeding in college-level coursework, it stands to reason that ACT College readiness rates would rise as well.

Credit Recovery For Struggling Students

Students facing academic challenges have also received targeted attention through an enhanced credit recovery program, promoted by Homewood High School (HHS) principal Zack Barnes. Instead of simply issuing failing grades and having students repeat courses in summer school, the school directs students to online credit recovery programs that allow students to go back and address the specific standards they failed to master.

Test Taking Experience and ACT Prep

HHS Assistant Principal Amanda Esslinger added that Homewood pays for all 9-11 graders to take the PSAT, another college readiness test. This increases students’ comfort level with multiple standardized and timed tests. The multiple measures also create a greater awareness of each student’s strengths and areas of needed growth. That’s useful both to the individual student and to teachers and administrators evaluating the effectiveness of instruction.

Homewood offers an ACT prep class during the school day that any junior or senior can take, giving all students access to preparation that used to be only available to families who could pay for private courses.

Conclusion

Increasing student success on the ACT is important for individual students and can be an important measure of academic effectiveness for schools as well. Schools that generated improvement pointed to some measures that were directly aimed at the ACT such as raising student awareness of the importance of the test and providing access to ACT preparation resources. However, those schools and systems that improved first emphasized a commitment to delivering instruction that allows students to meet and exceeds expected standards of learning for their grade level. They also emphasized exposing all students to the deeper levels of learning expected for college level academic performance.