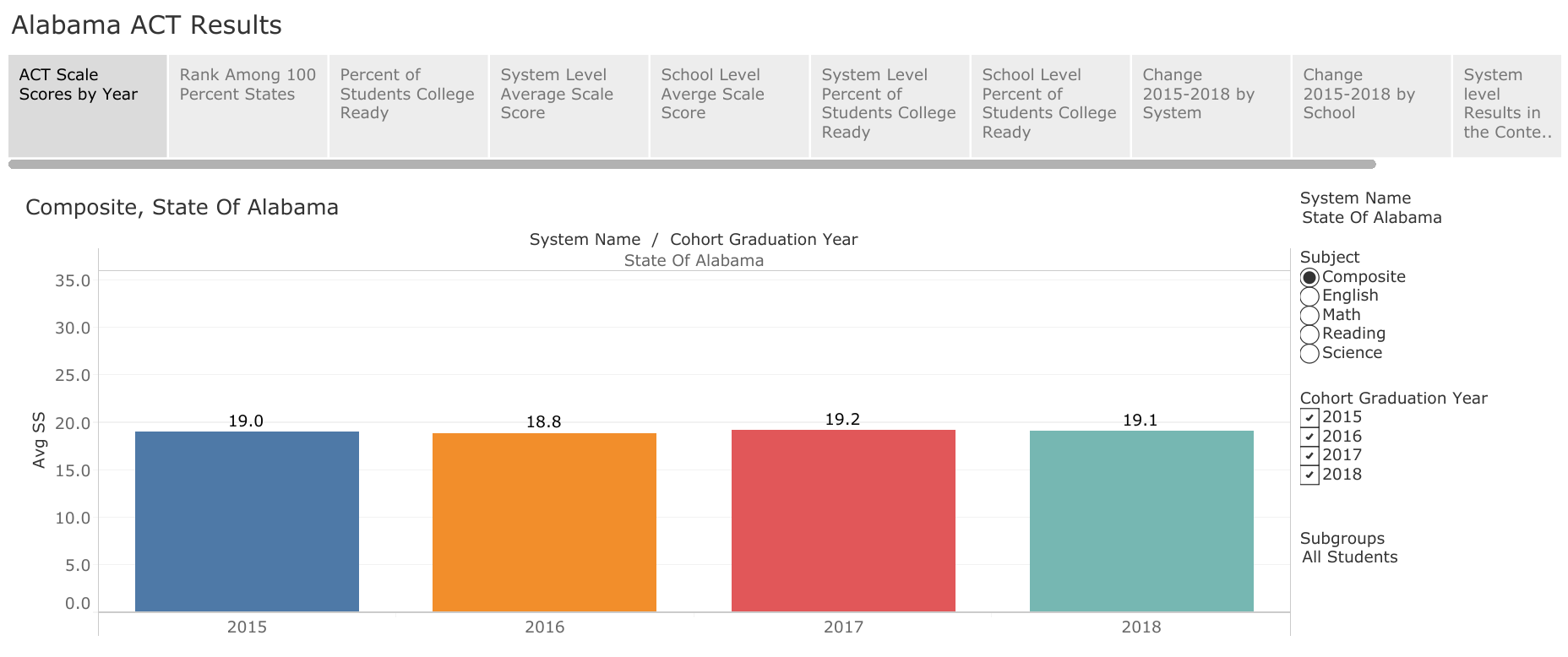

Alabama public high school students’ performance on the ACT was down slightly in 2018, after hitting a high point in 2017. Alabama students’ average score was 19.1 on a 36-point scale, compared to 19.2 in 2017. Over the past four years, Alabama scores have been stable, roughly paralleling the slight up and down of national scores.

Interactive charts in this report allow you to explore the results by system, and school, by subject, and by year.

How Does Alabama Compare?

The ACT is a test of college readiness and is used by colleges as a factor in the evaluation of applicants’ qualifications for admission. Alabama is one of 17 states that gives the ACT to all public high school students, whether they plan to apply for college or not. Among the states that give the test to all public high school students, Alabama ranks 13th, tied with North Carolina. The average scale score among the 100 percent states is 19.5.

More Alabama students, a higher percentage of enrolled seniors, and more students of color took the ACT in 2018, according to data provided by ACT and the Alabama Department of Education. This was particularly notable among Hispanic students. Though small in total numbers compared to whites and blacks, the number of Hispanics taking the ACT increased from 1,867 in 2015 to 2,886 in 2018 (55% increase). Black students taking the ACT increased over this period from 16,602 to 16,968 (2% increase), and whites slightly decreased from 29,337 to 29,100 (less than 0% change). Alabama public schools give the ACT in the junior year of high school. The final reported results here are for the students who graduated in 2018. Those students would have taken the ACT in 2017 at their own high school. If a student took the test subsequent to the administration at their high school, the student’s highest scores in each subject would be counted.

School Systems That Have Shown Improvement

In 2018, 85 out of 137 school systems in Alabama posted higher average composite scores on the ACT than they did in 2015. The top 10 systems in terms of improvement on students’ average composite score between 2015 and 2018 are listed below. A more complete listing can be found in the interactive charts.

| Rank | System | 2015 Average Composite Score | 2019 Average Composite Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Homewood City | 22.80 | 24.15 |

| 2 | Chickasaw City | 15.50 | 16.84 |

| 3 | Fayette County | 17.98 | 19.12 |

| 4 | Thomasville City | 17.33 | 18.46 |

| 5 | Auburn City | 21.32 | 22.41 |

| 6 | Macon County | 15.25 | 16.24 |

| 7 | Trussville City | 21.73 | 22.70 |

| 8 | Linden City | 15.42 | 16.37 |

| 9 | Coosa County | 16.36 | 17.29 |

| 10 | Arab City | 21.59 | 22.41 |

Keeping Demographics in Mind

On average, students from economically disadvantaged families tend to score lower on standardized tests than students who are not at an economic disadvantage. Similarly, schools where a higher percentage of the student body is economically disadvantaged, the average test score tends to be lower. Comparing schools that have similar demographics is a fairer way to evaluate relative performance. Scatterplot charts, like the one featured below, present score data and student poverty levels at the same time. The vertical position of the school or system is determined by the average test score, while the horizontal location of the school or system is determined by the percentage of the student body directly eligible for a free lunch under the national free lunch program.

ACT Scores and College Admission

Keep in mind that a composite score of 18 is considered a minimum threshold score for college admission at several state colleges. Others have lower thresholds, including open admissions. On the other end, a score of 25 or higher is expected at more competitive colleges, while 30 is the minimum threshold at some of the nationally elite schools such as Princeton. The table below lists the median entering ACT composite score students at Alabama colleges. Historically black colleges consider it part of their mission to admit students who may not have had the academic preparation to perform well on the ACT. The average ACT score for black students in Alabama is 16.5.