The following feature, which describes an alliance between the City of Montevallo, The University of Montevallo (UM), and Shelby County, marks the launch of an occasional series on creative cooperation between governments and other civic partners. Through the series, we hope to identify, share, and spread best practices and lessons learned.

Why We’re Writing This

Neighboring communities are inextricably linked in metropolitan or regional economies. Traditional ways of operating can lead to siloed thinking, inefficiencies, and, in some cases, counterproductive competition. Increasingly, neighboring governments and agencies are looking for ways to partner to achieve common interests. In recent years, PARCA has engaged in studying issues of municipal fragmentation and efforts to overcome its effects through cooperation among local governments in Greater Birmingham and in north Alabama’s Shoals region.

In April 2019, Greater Birmingham saw progress on cooperation with the crafting and signing of a Good Neighbor Pledge by members of the Jefferson County Mayors’ Association. Developed with the support of the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham, the Pledge seeks to increase trust and prevent incentive bidding wars between local municipalities over business relocations.

Meanwhile, the Committee for A Greater Shoals used PARCA’s report on its local government landscape to launch an array of civic improvement working groups, involving hundreds of citizens. Those working groups have now identified opportunities for further progress on intergovernmental cooperation, joint efforts on tourism, digital infrastructure upgrades, and increasing investment in higher education and training.

Montevallo’s Shared Investment in Shared Vision

Cooperative efforts in Montevallo between the county, the city, and the university which have been brewing for a decade, have in recent year produced a significant transformation.

For most of its history, Montevallo (current population 6,674) has been a trading center for the surrounding area. Area residents have worked at the university and local schools, in some small-scale manufacturing, in coal mining, timber, and in farming. If you visited Montevallo about a decade ago, you would find a typical Alabama small-town downtown, going through the usual struggles such towns face as retail and travel patterns shift to Interstate corridors.

Meanwhile, the university was something of a separate bubble. Founded in 1896, as the Alabama Girls’ Industrial School, the school grew into a respected college for women, and, after going co-ed in the 1950s, was re-christened the University of Montevallo in 1969. UM evolved into an unusual school: a public college, but one with qualities of a private college, due to its small class sizes and liberal arts concentration. While the university was obviously important to the town as an employer, there was an odd sense of separation from the downtown, despite the fact the two were only a few short blocks apart. Students tended to commute rather than live and spend in town.

Now, the lines between town and campus are deliberately blurred. The small town with a small college is beginning to have the look and feel of a “college town,” a place where campus life and energy animates the town and the town embraces and enlivens the college.

The downtown is updated, with new signage, lighting, and sidewalks, plus a couple of pocket parks and new greenery. What had been a long-shuttered, modernist Alabama Power office building on Main Street has been transformed into the University of Montevallo on Main, a classroom building that draws students and professors off the campus and into town for at least some of their classes. Another Main Street storefront has been renovated to serve as the University of Montevallo Bookstore.

On the edge of campus closest to downtown, a $25 million, 36,000 square-foot Center for the Arts building is rising. According to the University, the Center will include a 350-seat theater with state-of-the-art acoustics and technology for music concerts and theater performances, a 100-seat black box theater, and a courtyard suitable for outdoor performances and receptions. The building is expected to build on UM’s traditionally strong arts and theatre program, while also serving as a venue for drawing events and competitions from K-12 schools throughout the year.

The blocks between downtown and the University of Montevallo campus have been reworked with sidewalks and landscaping, an inviting pedestrian connection. The wrought iron gates to the university are open wide, and from them, a University of Montevallo purple “Welcome” banner hangs.

New sports venues have been added, strategically placed to intermix the college and the town. A new women’s softball field was built on city property across Main Street, adjacent to K-12 schools and the public library. Meanwhile, the school’s running track, developed with investment from the county, is open for use by the Montevallo public.

Blurring the Lines between Town and Campus

This mixing of university and town life is deliberate. It flows out of a strategy developed by the partners to bolster the University of Montevallo, the town’s biggest asset and one of the largest employers in Shelby County, and to build it into a more productive engine for the town’s economy and culture.

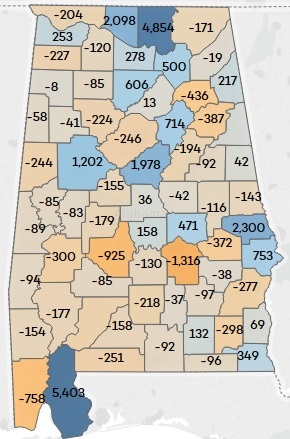

Big employers are valuable in Shelby County. The county is one the most affluent and fastest-growing in the state, but about half its residents work outside the county. UM employs almost 500 full-time employees with gross wages for non-student employees totaling $29.35 million in 2018. Campus and dining operations employ another 70, approximately 40 full-time, with gross wages of around $1.5 million.

Even before the three-way collaboration came about, Shelby County, recognizing the strategic importance of the University, began investing lodging tax revenue in University projects that would help the university recruit and retain students. Shelby County uses its lodging tax revenue to promote tourism and economic development. In those investments, the county looked for projects that would provide benefit to the local community as well.

A comprehensive plan for the City of Montevallo, developed in 2008, sketched a vision of a revitalized downtown, complete with interconnection to the University. However, progress toward realizing that vision began in earnest in 2012, with the City’s passage of a 1 cent sales tax and with the formation of a Montevallo Development Cooperative District (MDCD). Organized as a Capital Improvement Cooperative District under AL Code § 11-99B (2016), MDCD is a partnership between the city, the county, and university. MDCD can act like a corporation. It can buy, sell, or lease property, and enter into contracts.

The City of Montevallo pledged 90 percent of the revenue from that 1 cent tax to the MDCD, which, in turn, used that pledged revenue stream to issue $5 million in bonds. Overall, the city has invested about $6 million through the MDCD, about $1.75 million in joint projects and $4.25 million in city projects including paving, relandscaping, and the construction of a new city hall. Both within and outside the MDCD, the county has invested $4.5 million with another $900,000 pledged for projects now underway. Meanwhile, the University of Montevallo is providing $21.7 million of the funding needed for the new Fine Arts Center and has invested more than $1.1 million in other projects with MCDC and the county. Investment by local partners on transportation projects also drew in close to $5 million in federal funding.

Not every project flows through the MDCD and not every MDCD project involves more than one partner, but the District keeps communication constant between the partners, and when one or more of the partners want to engage in a joint venture, the mechanism is there and waiting. It also serves as a vehicle for operating ongoing cooperative ventures like the jointly-owned buildings Montevallo on Main and The Main Street Tavern, another MDCD-restored building now leased to a restaurant.

The public investment has spurred private interest and investment. A Montevallo chapter of Main Street Alabama has been formed, supported by local businesses. That group has spearheaded a grant program that has repainted building facades in the historic core of storefronts. Some of those storefronts are occupied with businesses new and old, and some are in the midst of cleaning or restoration. They share Main Street with chain stores like McDonald’s, KFC, Taco Bell, and CVS, but the chains have new urban signage and design, which blend better with the appearance of the historic core.

Dee Woodham, a former Montevallo councilwoman who continues to serve as Montevallo’s representative to the MDCD, said the vision for a revitalized college-oriented Montevallo formed over a decade ago, but it was not until the county, the city and the university joined together and committed resources to the vision that things started to happen. “This is an impactful way of doing nice things in a small town,” she said.

Challenges

The investments made at UM and in Montevallo are not just feel good improvements. They are strategic responses to challenges. All parties recognize that the University of Montevallo has been, and will be, facing stiff competitive headwinds.

In the early 2000s, the University of Alabama launched an aggressive effort to grow its enrollment from 20,000 to its current total of over 38,500. Colleges and universities across Alabama felt the effects of UA’s well-resourced recruitment efforts, sparking increased competition for in-state students.

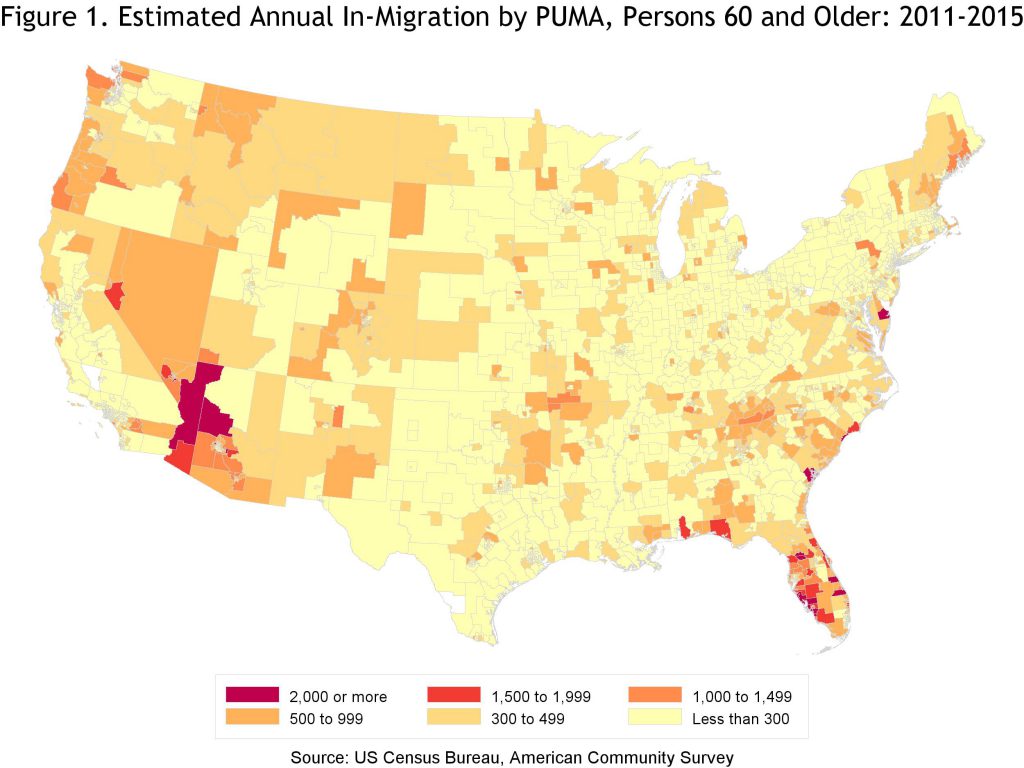

And because the rising generation is smaller and because the state hasn’t seen much in-migration, the pool of in-state, college-age students has been relatively constant and may actually decline in coming years.

While the University of Montevallo’s historic dedication to the liberal arts is a selling point, the current fashion in higher education, considering the cost of college, is to emphasize programs that more obviously and directly lead to careers. UM’s annual tuition and fees of over $13,000 are the highest among Alabama public colleges. However, its 13 to 1 student to faculty ratio is lower than any Alabama public college, and its tuition is lower than the private liberal arts colleges with whom it competes.

The University’s current enrollment of about 2,600 is down from about 3,000 several years ago.

Responding to Challenges

As a recruitment tool and to broaden its appeal, the University is adding sports teams, with the county aiding in that investment. The county helped develop the lacrosse field, allowing UM, which participates in NCAA Division II athletics, to become the second public university in Alabama to offer men’s and women’s lacrosse. That’s a draw for both in-state and out-of-state students who want to continue playing in college and don’t have many options in the Deep South.

The county also helped with the construction of a stadium for women’s softball, which was built on land provided by the City of Montevallo.

The University has also expanded other sports offerings hoping to attract scholar-athletes. It added a swimming team, taking advantage of an existing Olympic-sized pool at the student center.

On the slightly offbeat note, UM has a nationally-ranked collegiate bass fishing team, taking advantage of Montevallo’s proximity to the fertile lakes of the Coosa chain. UM also added an “Outdoor Scholars” program to showcase its proximity to the Black Belt’s fishing and hunting grounds.

And starting this fall, UM will field a competitive eSports team, with the aim of recruiting students who are interested in electronic gaming, in particular, a game called, League of Legends.

While UM’s investments haven’t yet produced a surge in enrollment, the University believes it has positioned itself for growth through its recruitment efforts, expansion of sports, and other investments like the Fine Arts Center and a new home for its School of Business. And the joint investments with the city have created an atmosphere more conducive to having students who will enroll in and live in Montevallo rather than commute.

Defining Goals and Expectations

For the partnership to thrive, all parties agreed that it was important to spell out their objectives, define the organizational structure, operate transparently, and come to a written understanding of expectations. The Shelby County Commission’s detailed resolution that endorsed the partnership describes underlying motivations and history of the partnership. Together, the parties agreed to articles of incorporation. Another practice followed by Shelby County when it commits to joint ventures is a performance contract, like the one adopted by Shelby County and the UM as a condition of the county’s support for the new fine arts center.

The county agrees to provide up to $1.2 million over seven years to support the project in order to aid the University’s recruitment and retention of students and the attraction of visitors to the community. But that contribution is conditioned on UM developing a schedule of events, performances, conventions, and competitions, targeting not only university students but also high school and middle school students. The University agrees to set goals for attendance, track it, and report back its results. UM has already laid out a draft calendar of more than a dozen proposed events each year through 2025. Depending on how well UM does in meeting performance expectations, the Shelby County Commission can decide to accelerate, slow down, or terminate its support to the project.

The MDCD has three members, one appointed by each entity. Within the parameters set out for it by its authorizing bodies, MDCD can operate more nimbly than a government. However, in MDCD’s case, the District functions as a public body under the open meetings law. Advance notice of meetings are posted. Decision-making takes place in public meetings. Minutes are taken and published on the web, as are financial reports and audits.

Caveats

While collaboration has clear advantages, it is not without risks.

In any partnership, questions can arise over whose interests are being served. For example, some townspeople worry that the town’s relationship with the university is too close. The mayor and two council members are university employees. A third council member is married to a university employee.

Janice Seamon, a Montevallo realtor involved in historical preservation causes, said cooperation is important and has produced positive, tangible results. But in her opinion, in any town, if the largest employer directly or indirectly employs the majority of the council, that has the potential to create conflict. “Having the major employer in control of city government is not good practice,” Seamon said.

Also, one of the virtues of the MDCD — its nimbleness and lack of bureaucratic structure — can lead to questions about accountability. Montevallo Councilman Rusty Nix points out that many of the projects that have run through MDCD are really city projects and don’t involve the other partners. Why, he asks, are these public expenditures run through MDCD, an alternative body on which the city’s representative is not an elected official? Why aren’t at least those solo projects reviewed for approval by the elected City Council?

Woodham, the former councilwoman and the current City of Montevallo representation to the MDCD, acknowledged that the potential for a conflict of interest exists with university employees serving on the council, but at the same time the town needs the interest and input from the university community. Woodham thinks that so far officials have been able to pursue mutually beneficial projects under terms fair to all parties. Ultimately, voters will pass judgment on that.

As for her representation of the city on MDCD despite no longer being an elected official, that’s up to the city council. Neither the county nor the university representatives are elected, but all are accountable to their appointing authority.

Measuring Success

The partnership effort of the county, the university, and the city has already achieved undeniable results. Time will tell to what extent success will fully flower.

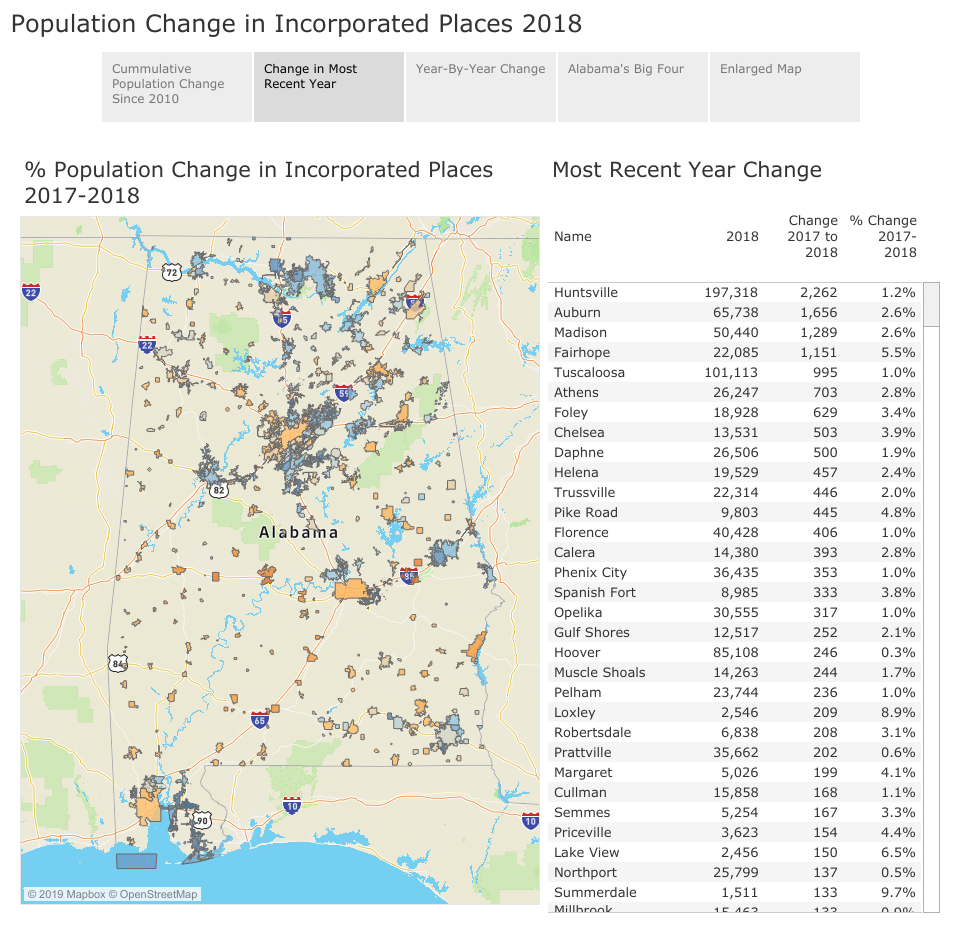

The City of Montevallo is showing population and revenue growth, above and beyond the extra revenue produced by the increased sales tax rate. The accumulation of improvements is creating a sense of new possibilities. There are still vacant storefronts to fill, but almost two dozen new businesses have opened in the past three years, including a bakery, a bar, a cake and coffee shop, a Taco Bell, and a popsicle shop. Coming later this fall, Slice Pizza plans to open in Montevallo, its third location in the metro area.

At the same time, the aggressive changes at the University of Montevallo have not yet yielded a surge in enrollment. UM is well short of its Fall 2019 goal of 3,000 undergraduates. Officials hope that as the new sports teams become established and as UM’s new full-time student recruiters in Georgia and Tennessee spread the word, interest and enrollment will gather steam and the investments made by the partners will pay long-term dividends for all parties.

This partnership may be a model that other colleges and communities in our state can explore.