In support of the work of the government and health care professionals involved in the Coronavirus containment effort, PARCA is gathering information and resources as the situation unfolds. Check back PARCA’s Coronavirus Resource page for updates.

In support of the work of the government and health care professionals involved in the Coronavirus containment effort, PARCA is gathering information and resources as the situation unfolds. Check back PARCA’s Coronavirus Resource page for updates.

The Alabama Legislature’s two-week recess is over, but the session will not resume on March 31. No date has been set to reconvene either house. The Legislature is constitutionally mandated to enact General Fund and Education Trust Fund budgets and end the session by May 18.

Enacted Legislation

Before the recess, the Legislature acted on one bill relating to COVID-19.

The Legislature approved, and Governor Ivey signed, HB 186 appropriating an additional $5 million from the General Fund to the Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) for COVID-19 preparation and response.

For perspective, ADPH’s fiscal year 2020 budget is $861,467,948, but only $52 million are state appropriations. This additional $5 million represents a 9.6% increase in the state appropriation. In its 2018 Annual Report, ADPH reported spending approximately 22.7% of state appropriations on infectious diseases.

Proposed Legislation

HB 448 proposes to expand Medicaid coverage for new mothers for 60 days after the birth of a baby to one year.

HB 447 proposes to expand Medicaid, as described in the Affordable Care Act.

Resolutions

SR 49 urges Congress to provide additional rental assistance to eligible families in USDA rural housing units. According to the resolution, there are approximately 13,000 Alabama families living in such units.

HR 107 urges the promotion, sharing and posting of practices to reduce the spread of infectious diseases.

SJR 40 asks Alabamians to fist bump rather than shake hands.

HJR 121 is a joint resolution from Democrats in both houses asking the Governor to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Other Actions

Senator Arthur Orr (R-Decatur) plans to file a bill providing businesses civil immunity from lawsuits that allege contraction of COVID-19 on those business’ premises.

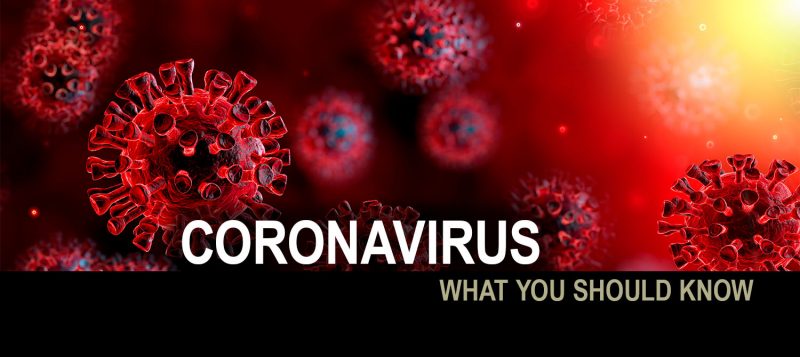

The latest estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau show a more broadly distributed pattern of population growth in 2019 with continued and accelerating strength in north Alabama counties and a surge across south and Southeast Alabama. Published last week, the figures estimate the populations of counties and metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) on July 1, 2019. Next year’s figures will be based on the actual census count now underway.

Between July 1, 2018, and July 1, 2019, population growth was more widespread in Alabama than it had been the year before: 29 counties saw growth compared to 22 in 2018.

That more dispersed growth included more positive growth in some rural counties, particularly in North Alabama and Southeast Alabama.

To be sure, the hottest spots for growth remain Madison and Baldwin counties’ populations. The Huntsville metropolitan statistical area (MSA), which includes Madison and Limestone, posted the strongest gain among MSAs, with an estimated 8,643 new residents. Nearby counties like Morgan, Marshall, Cullman, Colbert, and Lauderdale also gained.

Houston County, home to Dothan, had been growing steadily over the course of the decade, but in 2019 saw a jump of over 1,000 new residents according to the estimates. The growth in Houston and smaller gains in other counties bordering the Florida panhandle were likely sparked, in part, by businesses and individuals relocating in the wake of Hurricane Michael’s strike in October of 2018.

The tabs at the top of the maps allow you to select between views of numeric, percentage, or rates of change. State and national maps are available. The menus to the right of the maps allow you to toggle through options for the timeframe and select components of change. Maps include county-by-county birth, death, and migration rates.

The Birmingham metro area continued with slightly positive growth, though the estimates show its central county, Jefferson, losing residents in 2019. Shelby saw a higher gain in 2019 than in 2018, as did St. Clair. Blount, Chilton, and Bibb counties posted gains. Walker County’s population declined.

Montgomery’s MSA saw slightly positive growth thanks to an uptick in growth in Elmore and Autauga counties and far less outmigration from Montgomery County. Nearby, Lee County saw something of a pause to what has been blistering growth in the Auburn-Opelka area. Lee County added 886 new residents, according to the estimates. Lee had been adding more than 2,000 residents a year throughout the decade.

Mobile’s MSA, which consists of Mobile County, lost almost 700 residents according to the estimates. Despite their proximity and interrelation, Mobile and Baldwin County are considered separate MSAs. If the two counties were considered together, Baldwin’s growth would much more than offset Mobile’s losses and the area would be the second-fastest growing MSA in the state in numeric terms. MSAs for Dothan, Tuscaloosa, the Shoals and Decatur showed growth in 2019. The Anniston MSA, consisting of Calhoun County and Gadsden MSA consisting of Etowah County, both lost population.

Among non-metro counties, the trend of population loss continued. Rural counties in Alabama’s Black Belt, those along the border with Mississipi, those across south-central Alabama and in east Alabama, with the exception of the I-85 corridor saw population declines in 2019. Losses were particularly steep in Dallas County, which lost over 1,000 residents in 2019, according to the estimates. That was close to 3% of the county’s population. Since 2010, Dallas County is estimated to have seen a 15% decline in its population.

For 2019, the Baldwin County MSA’s annual growth rate of 2.5% ranked 13th out of the nation’s 383 metro areas. Huntsville’s growth rate of 1.9% ranked No. 23. Birmingham ranked No. 229 out of 383, Montgomery, 261, and Mobile, 299.

Looking back to 2010, both Madison and Baldwin counties have added around 40,000 people since the beginning of the decade, according to the estimates.

Alabama’s other big gainers were the major college towns, which also happened to be on automotive assembly corridors. Lee County, home to Auburn, gained almost 25,000 residents since 2010 and Tuscaloosa added almost 15,000. Suburban Shelby County added over 22,000.

Over the same period, Mobile and Jefferson counties were flat in terms of population totals for the decade. Montgomery lost almost 3,000 residents.

Those changes seem modest, but below the surface, major shifts occurred. Each of those counties saw large gains through natural increase (births outnumbering deaths by 10,000 to 15,000). At the same time, though, they exported more residents than they gained through natural increase (15,000 to 20,000 net outbound movers).

However, bringing the large central counties back to even was international migration, with each of the central counties attracting around 4,000 to 6,000 net new arrivals from abroad over the decade.

Adjacent to Jefferson, Shelby and St. Clair Counties continued to grow. Madison’s neighbor, Limestone actually outgrew Madison County in percentage terms. Montgomery’s neighbors Autauga and Elmore gained.

Rural Alabama counties, including both the Black Belt and south-central Alabama, along with the heavily forested counties along the Mississippi border have lost population. In numerical terms, Dallas County has lost the most of any county, with an estimated 6,617 fewer residents in 2019 than in 2010. More urbanized Calhoun County has lost almost 5,000 residents according to the estimates with Walker and Macon counties both losing well over 3,000, as well.

PARCA has updated its interactive maps and charts that allow users to explore local population changes and trends. PARCA tools for state-level population estimates were updated earlier this year. Estimates for cities will be released this summer. The next release of information for county and MSA population totals should come next year from the actual Census count. The Census is currently underway; however, considering the challenges created by the Coronavirus outbreak, it would be impossible to predict when the count will be completed.

While the COVID-19 pandemic rightly consumes so much of our attention, it is important—and perhaps comforting—to remember that other important aspects of public life continue. One of these is the 2020 Census.

Census information began to arrive in the mail last week, and already, people are participating. An accurate Census count is now more important than ever as state and local governments will be coping with a very different post-pandemic reality.

The map below, provided by the Census Bureau, reports self-response rates by state, congressional district, county, city, and census tract. The self-response rate, sometimes called the initial response rate, is the percentage of households that respond to the initial request to participate. Households that do not respond to this initial request receive additional requests and, ultimately, a visit from a Census worker.

Tracking the self-participation rate is a good measure of the effectiveness of Census promotion efforts and helps the Census Bureau adjust strategies. The self-response rate does NOT indicate the total percentage of households counted.

For more on the 2020 Census, see The 2020 Census: What’s at Stake for the State of Alabama published by PARCA last fall.

Are Alabamians participating?

As of March 25, Alabama’s self-participation rate is slightly ahead of the nation at 27.7% compared to 26.2%. For comparison, the state’s final self-response rate in 2010 was 62.5%. Within Alabama, Autauga County leads all counties at 33.4%.

You can complete the Census here.

The map below allows you to explore response rates at all geographic levels and is updated every day at 2 PM CST.

Alabama spent 2019 looking back at its first 200 years of statehood. In 2020, it seems appropriate to look forward to the next 100.

PARCA’s annual meeting, held Friday at Birmingham’s Harbert Center, was inspired by that theme: Taking lessons from the past in order to chart the way to a better future.

Along with a detailed look at the demographics shaping our state, it also included a series of experts discussing what the future holds for education, corrections, health and opportunity in Alabama.

The meeting featured Governor Kay Ivey describing her administration’s strategic efforts to raise educational achievement and to improve access to and the effectiveness of workforce training to meet the increased demands of the 21st-century economy.

James H. Johnson Jr., professor of business and director of the Urban Investment Strategies Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, spoke of the demographic changes that are already reshaping the state and the nation. Both Alabama and the nation as a whole are undergoing seismic shifts that will change the country.

Recognizing and preparing for these changes will be essential if Alabama is going to be competitive in coming decades. A fuller discussion of Johnson’s observations can be found in a paper Johnson published last year in Business Officer, a publication of The National Association of College and University Business Officers

Though Alabama has not grown as rapidly as magnet Texas and the Southern states on the East Coast, it will feel the same shifts. The native-born white population is not reproducing fast enough to replace itself, much less grow in numbers. Meanwhile, Hispanics, blacks and other minorities are younger on average and will constitute a greater share of the population over time.

Neil Lamb, the Vice-President for Educational Outreach at Huntsville’s HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, highlighted factors that will shape education over the next 100 years: the ease of information access, advances in the science of learning, the rise of personalized learning, and the development of data-driven classrooms that allow for in-the-moment shifts in teaching strategy.

Lamb said these innovations offer great promise but they can’t be deployed haphazardly or without adequate support for the teachers that will need to use the tools to help children succeed. There must be attention paid to equity in spreading technology and adequately resourced professional development to support its implementation. Lamb, who served on the Governor’s Advisory Council for Excellence in STEM, pointed the audience to that Council’s recently released report: Alabama’s Roadmap to STEM Success.

Among its first step recommendations is a proposal that is now before the Alabama Legislature: The State Department of Education proposes to hire a team of 220 math coaches to provide statewide support for improving math instruction.

The STEM Success report includes the recommendation that an evaluation process be built into the math coach initiative so policymakers will be able to measure its impact and adjust the strategy in pursuit of success.

Bennet Wright, Executive Director of the Alabama Sentencing Commission and past President of the National Association of Sentencing Commissions, challenged the audience to think differently about prevailing but largely unexamined assumptions about crime and punishment.

Wright said Alabama has created one of the most complex systems of criminal justice and corrections in the United States. New laws are laid on top of old, but the old are not repealed. A multitude of different agencies and players operating with distinct motivations keep the institutions from functioning together as a system. Wright’s presentation materials can be accessed here.

Governor Kay Ivey’s Study Group on Criminal Justice Policy, chaired by Justice Champ Lyons, released a report and reform recommendations just last week. A letter with recommendations can be accessed here.

The Study Group’s report can be accessed here.

Monica L. Baskin, Professor of Preventive Medicine and director for Community Outreach and Engagement at the O’Neal Comprehensive Cancer Center at UAB, described the tremendous cost borne by Alabama as a consequence of poor health and pointed to opportunities to address health problems and health disparities before they become issues.

According to estimates by the Milken Institute, the direct and indirect costs of chronic disease in Alabama total more than $60 billion a year, more per capita than any other state except West Virginia.

In her presentation, Baskin cited several promising initiatives aimed at preventing the development of chronic disease, and encouraged partners statewide to increase innovation, collaboration, and equitable dissemination in order to get information to the people and places that need it most.

And Michael Chambers, Associate Vice President of Research at the University of South Alabama, argued that we, as a state, need to speed up our pace of experimentation and change. Chambers, an experienced businessman, entrepreneur, and attorney, said businesses have had to learn to act quickly, be flexible, be competitive, to avoid complacency, and to plan on change. If Alabama’s leadership and citizens expect to be competitive, Chambers said, we should do the same.

In preparation for the program, PARCA produced a series of charts that present key indicators of the economy, health, education, and criminal justice over a long time span. Interactive versions of those charts are available below. The charts compare Alabama to the U.S. average or to other Southeastern states. In the interactive version, you can change comparison states.

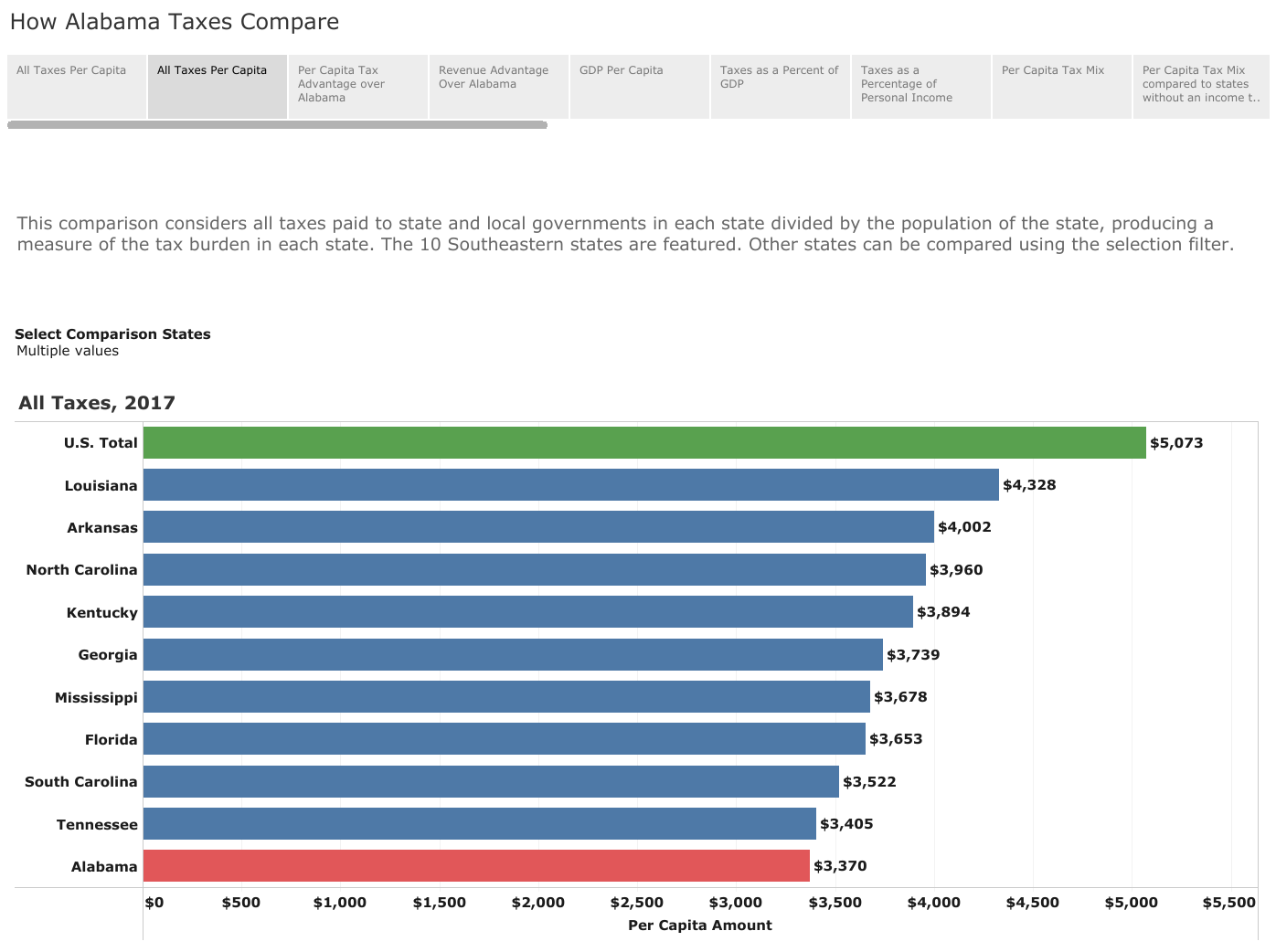

Despite gaining some ground in 2017, Alabama state and local governments still collected less in taxes than state and local governments in any other state on a per capita basis. That’s been true since the early 1990s and partially explains why Alabama struggles to provide the same level of public services as other states.

PARCA’s 2019 edition of How Alabama Taxes Compare describes Alabama’s tax system and how it compares with tax systems in other states, based on the latest data available from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

In addition to the PDF version of the report, the interactive charts below allow you to explore the data on your own. For better viewing, expand to the full-screen view by clicking on the button on the bottom right of the display below. Navigate through the story of Alabama taxes using the tabs at the top of the interactive display.

Alabama is at risk of losing federal funding, a congressional seat, and an Electoral College vote. These outcomes are based on projected results of the 2020 Census.

The 22nd decennial census, mandated by the U.S. Constitution, begins on April 1, 2020. The census counts every person living in the United States. Business, industry, nonprofits, researchers, and governments use this information to understand and serve the public. The Constitution requires the census. Federal law requires all people living in the U.S. to respond.

The census is always a challenging project, but there are additional complications in 2020.

• The 2020 Census will be the first census administered primarily online.

• Proposals to add a citizenship question have created confusion in many communities.

• Trust of government is at near historic lows.

• The Census Bureau has reported to be behind in hiring field staff.

Regardless, the census results will have a profound impact on every community in America. While ultimately the responsibility of the federal government, the census is important to the states, and most invest substantial resources to promote the census.

As of this writing, Alabama has created the Alabama Counts! taskforce to promote the census and has committed $1.24 million, or $0.25 per capita, to the effort, compared to an average of $1.37 across the country, based on data reported by the National Council of State Legislators.

The stated goal of Alabama Counts! is to increase Alabama’s initial participation rate beyond the 72 percent reported in 2010. This figure represents the number of households that returned a census form by mail. Those who did return a form by mail received a visit from a census worker.

While increasing Alabama’s initial participation rate is a worthy goal, it is worth remembering that the national initial participation rate in 2010 was only 74 percent. A significant increase in the initial participation rate will be difficult and will require concerted effort from local officials in Alabama’s 67 counties and the 460 towns and cities recognized by the Census Bureau.

Even if the efforts of Alabama Counts! are exceedingly successful, Alabama may well lose a congressional seat. Census workers simply cannot count people who are not here. And Alabama is simply not growing as fast as other states.

But how does Alabama compare? What options do we have? Find out the answers to these questions and more in the full report.

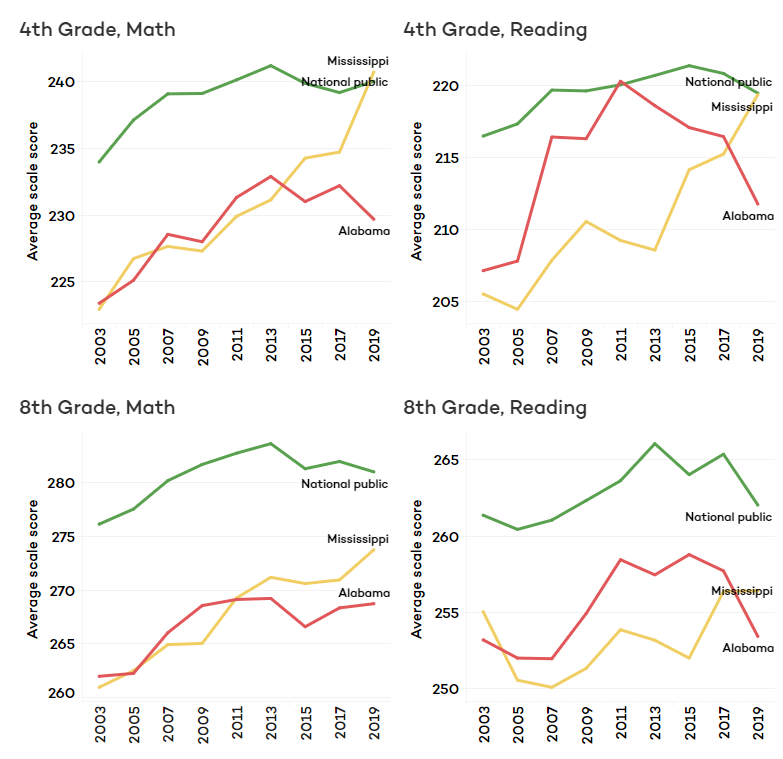

When the 2019 results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) were released last week, the good news was that fourth-grade students in our neighbor state, Mississippi, scored at the national average in both reading and math and that eighth graders there made significant gains in reading and math as well.

On all four measures, the average score for Mississippi students exceeds those of Alabama students, despite Mississippi’s higher level of poverty and higher percentage of students of color. The interactive chart below traces the average scale scores for Alabama and Mississippi students on the NAEP since 2003 on each of the four measures. The green line represents the average of public school students nationally. Other tabs in the chart allow you to explore other ways of looking at the data, including comparing demographically similar groups of students across states. In each of the main demographic and economic categories, Mississippi students are outperforming Alabama’s. The NAEP reading and math assessments are given every two years to a sample of students in each state, the sample representing the demographics of the state. It is the same assessment from year to year, and it is administered nationally. Known as the Nation’s Report Card, NAEP serves as the principal national measure of academic proficiency for U.S. education.

Mississippi’s rise was not a surprise; it was part of the plan: a serious, sustained, and strategic effort to improve. In a 2018 report, Leadership Matters, commissioned by Business Education Alliance, PARCA described Mississippi’s strategic plan for educational improvement.

Mississippi has had a consistent and cohesive educationally-focused leadership in the Governor’s office, the State Legislature, and at the Mississippi Department of Education. Current superintendent Carrie Wright was recruited in 2013 from a leadership position in the District of Columbia’s rapidly improving public schools. Under Wright, and with the backing of an appointed state school board, Mississippi has operated under a plan that includes goals, objectives, and clearly articulated strategies aimed at meeting those goals. To track progress on the implementation of strategies and progress toward goals, the superintendent delivers an annual update that details actions taken to advance toward those goals.

Mississippi borrowed some aspects of its approach to improving reading from Alabama’s Reading Initiative. And more recently, Alabama borrowed from the Mississippi model. Earlier this year, the Alabama Legislature adopted a Literacy Act, similar to a Literacy-Based Promotion Act Mississippi adopted in 2013. Mississippi developed its own student assessment test for grades 3-8, MAAP, which was first deployed in the 2015-2016 school year. Alabama hopes to deploy its own state-developed assessment in the spring of 2020.

Over the long term, both Alabama and Mississippi have made progress in both reading and math. However, during Superintendent Wright’s tenure in Mississippi, Alabama has had five different superintendents. The State Department of Education did develop a state plan for education, Plan 2020, in 2012, but it was never fully developed and implemented and was shelved as subsequent superintendents came and went.

In 2011, just eight years ago, Alabama enjoyed the national spotlight when NAEP was released. Alabama fourth graders scored at the national average, having made the largest improvements in the U.S. That growth coincided with and has been generally attributed to the Alabama Reading Initiative (ARI). ARI emphasized a schoolwide commitment to getting all students reading at grade level, with an emphasis on Kindergarten through third grade. ARI placed a reading coach in every Alabama elementary school and required intensive professional development to teachers on research-based approaches to teaching reading.

However, after that achievement, and in the face of a constrained budget, funding for ARI was reduced, and schools were allowed to repurpose the state-funded reading coaches for other purposes. Reading scores on NAEP began drifting and in 2019 dropped sharply in both fourth and eighth grades.

Earlier this year, the Legislature adopted the Literacy Act, which will require that third graders be able to read, or they will be held back to repeat third grade. The Literacy Act, modeled after similar legislation in Mississippi and other Southeastern states, is expected to add urgency to reading instruction and to addressing reading challenges like dyslexia. ARI’s funding was also increased by $6.5 million, though at $51 million per year, that’s still far from the $64 million it received at its peak in 2008. Education leaders say the program will be restored to fidelity.

While the 2019 reading results on NAEP were distressing for the severity of the drop, the math results for Alabama students were equally disturbing. Alabama school children in both the fourth and eighth grade had the lowest average test scores in the United States. It’s a familiar position for Alabama. Alabama ranked behind all other states in 2015. In 2017, Alabama students climbed a couple of notches in the rankings, but slipped back into last this year.

The state’s strategy for addressing math is less clear. In March of 2019, Gov. Kay Ivey put on hold new math standards, which had been developed by a statewide panel of educators. Ivey postponed adopting the changes to the math course of study after some conservative groups, who are opponents of the Common Core state standards, voiced their objections. In a letter to State Superintendent Eric Mackey, Ivy asked that Alabama’s new proposed math curriculum be compared to the math course of study for the top six performing states on the NAEP: Massachusetts, Minnesota, the Department of Defense’s educational system, Virginia, New Jersey, and Wyoming.

Considering Mississippi’s results, its approach to math should be examined as well. Mississippi did adopt the Common Core standards. Judging by national results, it safe to say that Common Core did not cause NAEP scores to leap. But it’s also true that states that did not adopt the Common Core have seen declines on the NAEP as well. Other factors may be contributing to an overall stagnation in educational progress. However, with Mississippi bucking the trend, Alabama would be well served to take note and inspiration from our neighbor’s progress.

The thriving economy produced another year of surging tax collections for Alabama’s General Fund and Education Trust Fund (ETF), the two primary accounts that provide state funding for government operations. The better-than-projected results put the state in a good position to meet current obligations and weather a downturn should it arise.

It also appears that budgeting changes made by the Legislature in recent years have created more balance in revenue growth between the two funds.

According to the state’s financial reports for the fiscal year that ended on Sept. 30, the taxes and revenues that feed the General Fund were up 8% over 2018. Revenue to the ETF increased by 7% over the previous year. It is unusual that the General Fund’s rate of growth exceeded the ETF’s. Historically, the ETF, which contains major growth taxes like the income and sales taxes, grows faster than the General Fund.

In dollar terms, General Fund revenue increased by $155,837,199.45 to a total of $2,151,954,704, while ETF collections rose by $461,710,824 to $7,215,276,202.89. Collections in both funds exceeded projections.

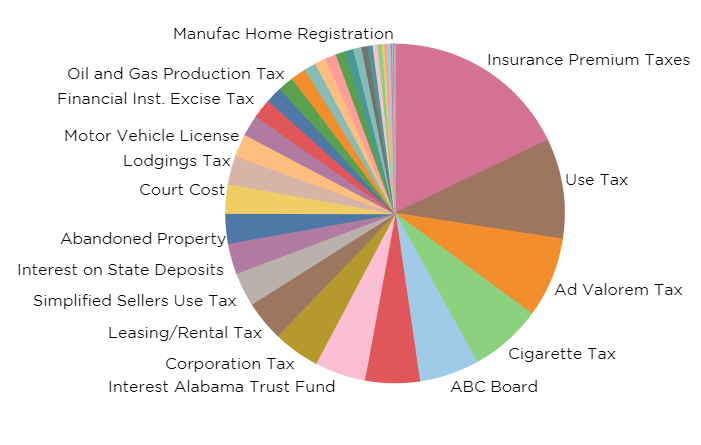

Alabama’s General Fund revenues are derived from a hodgepodge of taxes, most of which moved in a positive direction. General Fund spending supports health programs, like Medicaid and the Departments of Health and Mental Health, as well as law enforcement, the judicial and corrections system and other public safety agencies, plus a variety of other non-education programs.

In dollar terms, revenues from insurance premium taxes are the biggest contributor to the General Fund, providing $385 million or 18% of total collections. Those taxes, which are applied to the premiums paid by insurance policyholders, grew 10 percent over 2018, putting an additional $35 million into the General Fund.

There may be several reasons why this tax is growing at a faster rate than the overall economy. Since more people are employed and have more stable resources, more of them might be buying insurance in contrast to tougher economic times. At the same time, insurance companies may be charging more in premiums as they rebuild reserves needed to cover storm events and rising costs.

The Insurance Premium Tax is set to become an even bigger contributor to the General Fund in future years. A fixed amount of the tax, $31 million, had flowed into the Education Trust Fund. That division of the tax will end, and the total tax will flow into the General Fund. However, the transfer of this revenue comes with the understanding that the General Fund will have to cover the cost of the ALL Kids Children’s Health Insurance Program in future years, an expense that will rise over time.

In percentage terms, the tax that experienced the biggest jump in both its contribution to the General Fund and its rate of increase was the Simplified Sellers Use Tax. This is a tax paid on purchases made over the Internet and delivered to Alabama. Originally established in 2015 as a voluntary method for out-of-state sellers to remit sales tax to the state, the law has been increasingly tightened to require businesses that have significant online sales to participate. A 2018 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, known as the Wayfair decision, gave further authority to collect taxes on online sales.

As more online retailers came aboard in 2019, General Fund revenue from the source jumped by 136% or $40 million to a total of $70 million for 2019. The General Fund gets 75% of the Simplified Sellers Use Tax. The remaining 25%, amounting to $23 million in 2019, went to the Education Trust Fund. So, the total revenue from the Simplified Sellers Use tax in 2019 rose to $93 million compared to $40 million the year before.

Growth in this tax will likely continue as online sales continue to rise, but the rate of increase should not be nearly as high in the future.

Also helping boost the General Fund were higher interest rates. The interest paid to the state on its cash deposits jumped by $31 million in 2019 to a total of $63 million. Interest rates have subsequently fallen so this revenue source may not be as robust in 2020.

The Use Tax, the General Fund’s second-largest source of revenue, saw a respectable 3% growth, bringing in an additional $6.8 million for a total of $205 million. The Use Tax is collected on out-of-state purchases or leasing of equipment or machinery.

Revenues contributed by the state-regulated alcohol sales were up by 6.5% to $123 million. Property taxes were up 4% to $165 million. The lodging tax jumped 10% to $59 million. Analysts believe a strong year at Baldwin Counties beaches provided a boost, assisted by increased tourism to Montgomery with the opening of the National Peace and Justice Memorial.

Some tax sources declined. Cigarette taxes continued their long slow decline, down 4 percent or $5.6 million. Still, cigarette taxes, which contributed $149 million in 2019, are the 4th largest tax source in the General Fund. Tax collections on vaping products increased 62% but are a very small source of revenue at $2.3 million for the General Fund in 2019.

While the $19 million contributed by the Cellular Phone tax appears to be an increase, base collections actually declined in 2019. The total collections for 2018 were depressed by a refund of the tax paid out as a result of a lawsuit. For the most part, mobile telephone companies no longer charge customers for calls but instead charge for data. Calling plans are taxed; data plans are not subject to tax.

Taxes on automobile titles dropped 6% after several years of gains. The decline could indicate a slowdown in auto sales, a development that would introduce a dark cloud to Alabama’s otherwise sunny economic horizon.

In the interactive chart below, you can compare trends in taxes since 2015. The menu on the right of the chart allows you to decide which taxes appear in the view.

Strong growth in income and solid sales tax growth powered another year of growth in the Education Trust Fund. Those two taxes, both of which are earmarked for education, supply over 90 percent of the education budget. In 2019, income tax collections made up 63% of ETF deposits, while sales taxes contributed 28%.

Income taxes were up $340 million, or 8%, for a total of $4.5 billion. According to financial reports, individual income tax receipts were up 6%, while corporate income taxes increased 15% over 2018. When refunds are taken into account, individuals paid $4.2 billion and corporations $455 million in income taxes.

Along with the general economic growth, the sharper rise in corporate tax collections was likely spurred by the cut in federal corporate income taxes, enacted in December of 2017. Federal income taxes are deductible from Alabama income taxes. With corporations paying less in Federal income taxes, that meant corporations kept a greater share of profits, leaving more corporate income for Alabama to tax.

Sales tax collections rose 6%, to $2 billion, contributing an additional $105 million to the ETF. Total sales tax receipts increased 4%, while the amount held back to pay state agencies decreased. The Department of Human Resources received a smaller sales tax refund because DHR is paying out less in SNAP benefits. The Alabama Department of Revenue also decreased the amount it assessed the state for sales tax collection.

Beyond the income and sales taxes, as noted above, the ETF portion of the Simplified Seller’s Use Tax grew by 136%. In the case of the ETF, that provided an additional $13 million for a total contribution of $23 million. The third-largest contributor to the Education Trust Fund is the utility tax, which brought in $401 million, which was a $5 million or 1% increase over 2018.

According to Finance Director Kelly Butler, the General Fund ended with a $275 million balance that will be available to appropriate in future budgets.

For the ETF, it’s a little more complicated, due to rules set up under the Rolling Reserve Act, a budgetary control measure designed to curb unsustainable spending and to generate a cushion for use during economic downturns.

According to Butler, the ETF generated an “overage” of $579 million in 2019. Of that, $66.5 million, or 1% of direct budgeted spending in the ETF, will be shifted to the ETF’s Budget Stabilization Fund.

The remaining $512 million will be shifted into the Advancement and Technology Fund. That money will be available for appropriation during the next legislative session to K-12 schools and colleges and universities for spending on non-recurring expenses such as deferred maintenance, school security measures, and educational technology or equipment.

The 7% growth rate for the 2019 ETF will be added to the calculation of the Rolling Reserve’s built-in cap on the growth of education spending. That budget cap is calculated by taking the ETF’s growth rate in each year of the past 15 years, dropping the year with the lowest growth rate, and then finding the average rate of growth for the remaining 14 years.

Despite the good results this year, that overall average will be down slightly. Thus, the allowed rate of growth in spending will be slightly lower in the 2021 budget than it was in the 2020 budget.

That’s because the year dropped from the 15-year window, 2004, was one of the extremely high growth years that preceded the Great Recession. In those years, recurring revenues to the ETF were increasing around 10 percent per year.

The average growth rate will be declining for the next couple of years as those high-growth years drop out of the calculations.

While a final calculation hasn’t been made, it is expected that the spending cap on the 2021 Education Trust Fund Budget will be somewhere between $300 and $400 million over the 2020 Education budget, which totaled $7.1 billion.

It’s important to remember that the Rolling Reserve Act creates a cap on increased spending. The Legislature is in no way obligated to spend up to the cap.

Both the $2 billion General Fund and $7 billion Education Trust Fund are only part of the picture when it comes to paying for the operation of state government agencies. Beyond the tax sources detailed above, other state taxes are earmarked for certain purposes and sent directly to a designated agency.

There are also huge inflows from the federal government, particularly supporting Medicaid and other health programs, road construction and maintenance, and education. The federal contribution is a similar amount to what is generated by state taxes.

Other state agencies generate revenue. Colleges and universities charge tuition. Hunters and fishermen buy licenses that help fund the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Companies buy permits that help pay for inspections by the Alabama Department of Environmental Management. Those federal and state revenues are then spent supporting the agencies.

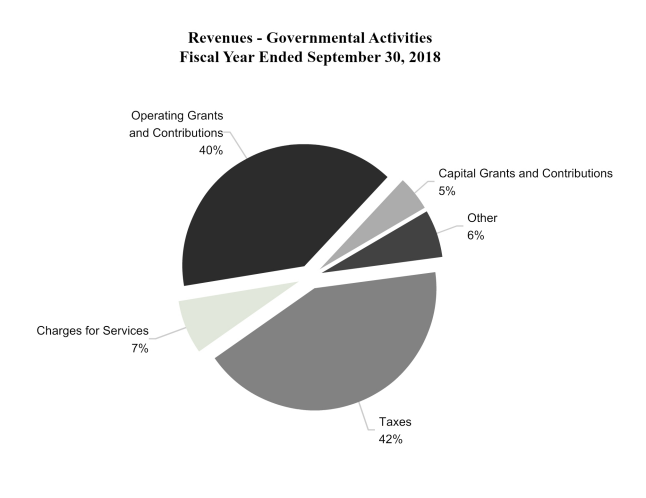

Alabama’s most recent Comprehensive Annual Financial Report (CAFR) details revenues and expenditures for Fiscal Year 2018. In terms of revenue, the CAFR indicates that total revenue was a little over $22 billion, more than double the tax collections deposited into the ETF and General Fund. The CAFR provides the chart below to illustrate the sources and proportion of all the revenues supporting the state governmental activities.

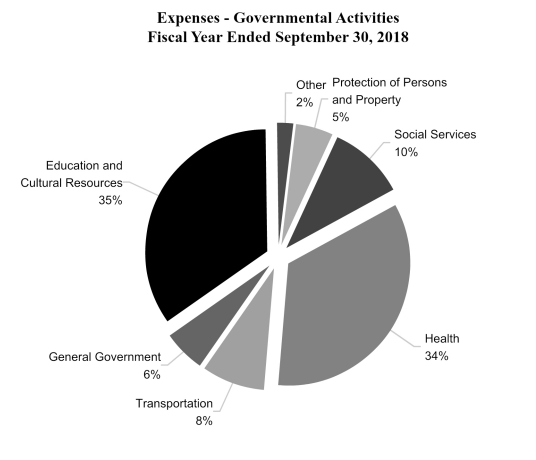

The CAFR also presents the government’s expenses for 2018, broken down by category of spending. On the surface, comparing the sizes of the General Fund and the ETF, it appears that we spend significantly more on education than we do on other functions of government. However, when federal funds and other earmarked taxes and revenues are taken into account, there is a more equal distribution of spending, with about one third spent on education and culture, about one-third spent on health, and one third spent on other functions: roads, law enforcement, the courts, prison, general government.

Any effort to promote cooperation between governments quickly runs into skepticism.

Cities and their citizens are self-interested, the thinking goes. They are not going to give up their advantages. They’re not going to be charitable to a neighboring community, just for the sake of being nice.

And the skeptics are right.

However, that doesn’t foreclose opportunities for cooperation. In fact, self-interest is the starting point for cooperation.

That’s one the lessons learned on the way to the Good Neighbor Pledge, an agreement signed earlier this year by about two dozen mayors in Jefferson County. Under the agreement, mayors pledged not to encourage or incentivize the relocation of local businesses from neighboring cities to their own. In so doing, the mayors hope they’ve solved a problem all of them were facing: a growing demand and expectation that local governments provide tax incentives to retain or attract businesses.

On the surface, signers of the Pledge appear to be giving up advantages and competitive tools in economic development. However, because almost all the key governments participated, the pledge resets the rules of the game, short-circuiting counter-productive and mutually damaging competitive battles that were costing all cities time, attention, and tax dollars while providing no net benefit to the region.

This feature is part of an occasional series on creative cooperation between local governments and other civic partners. Through the series, we hope to identify, share, and spread best practices and lessons learned.

The Good Neighbor Pledge grew out of an effort by the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham (CFGB) to understand regional challenges and to identify options for addressing those challenges. If not for the background research and dissemination of the findings, the Good Neighbor Pledge likely would not have come about.

After arriving in Birmingham in 2014, CFGB president and CEO Chris Nanni kept hearing from Birmingham-area leaders that the fragmented nature of the region, 35 municipalities in Jefferson County alone, was interfering with the region’s ability to effectively address problems or pursue an over-arching vision for the community.

With funding from a key circle of the Community Foundation’s Catalyst donors, the Community Foundation commissioned PARCA to research whether Greater Birmingham’s lack of cooperation was negatively affecting its ability to compete and if so, how other cities and metros have overcome fragmentation and moved toward a more unified approach to community progress.

To help frame the issues and provide response and guidance to the study, CFGB formed a broadly-representative strategic advisory group of Birmingham area leaders who were consulted throughout the research process. After the report, Together We Can, was published, the leaders from that Strategic Advisory Group were also essential in carrying the information and conclusions out to the community.

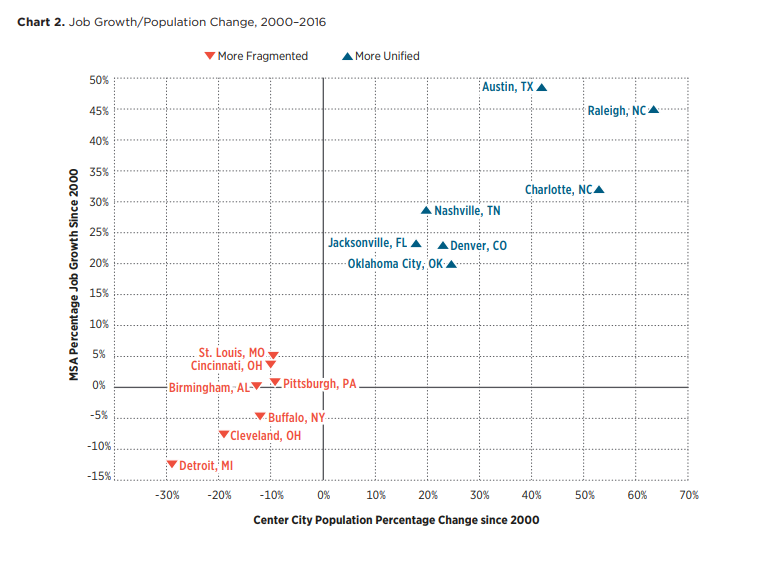

Published in June 2017, Together We Can concluded that Birmingham and other similarly fragmented cities consistently performed more poorly on economic and social measures than more unified metros. Cities around the country have long worked to overcome the challenges presented by fragmentation, and the report described four organizational models used by cities to counter fragmentation and increase cooperation.

After releasing the report, the Community Foundation and representatives of the strategic advisory group hand delivered copies to community leaders, spoke to civic clubs, and participated in radio and newspaper interviews and panel discussions. Neither the report nor the CFGB argued for a particular approach to increase cooperation. Nor was the cooperation conversation centered around a particular project or issue. It instead described approaches other cities took and encouraged Birmingham citizens and leaders to find a response that fit local circumstances.

“The education piece was essential,” Nanni said

That neutral approach was important because the prevailing climate among elected officials in Greater Birmingham was suspicion. That was clear during an early presentation to the Jefferson County Mayor’s Association.

“The first time we presented to them there was a lot of tension in the room, particularly among the incumbent mayors. For so long, the atmosphere was one of suspicion and competition. Zero trust. But as they came to see we weren’t trying to force them into something, they started warming up,” Nanni said.

The publication of the report preceded an election cycle in which several mayors’ races were on the ballot. Regional cooperation became an issue talked about in mayoral and council races that took place across the metro in 2017.

And it just so happened that among the new crop of mayors, there were several new faces who were open to new ways of doing things.

When attempting to break old negative patterns, it is tempting to propose starting from scratch, inventing a new organization or governmental authority to shape a new reality.

However, it’s sometimes best to put existing institutions to work solving problems rather than inventing a new one. In Jefferson County’s case, Together We Prosper proponents looked for an existing cooperative structure that could be repurposed, energized, or motivated to drive cooperation.

The Jefferson County Mayors’ Association emerged as a candidate. It had some legal standing and functionality, but, in the opinion of many of the participating mayors, it wasn’t living up to its full potential. The mayors had a monthly meeting that was paid for by a rotating cast of lobbying groups who got an audience with the mayors in exchange for paying for their lunch. Mayors got to network and casually discuss common experiences, but there was no push to collaborate, innovate, or address common problems.

The Community Foundation encouraged and sponsored a half-day summit for the Association, during which it was hoped that the mayors could find an issue they could rally around addressing.

The Community Foundation provided a facilitator to get the conversation going, but the mayors chose the topics to explore.

So it was the mayors themselves who coalesced around a challenging initiative: ending the bidding wars for local businesses. And since they chose it, they felt ownership of the initiative.

Local governments across the country are waking up to the fact that offering economic incentives for local business relocation is ultimately a losing proposition.

In 2004, communities in the Metro Denver areas enacted a Code of Ethics designed to end business poaching and promote regional cooperation around economic development. Many others have followed suit. Just this year, Missouri and Kansas found a way to end an incentives arms race that was allowing companies to reap incentives by moving between the Missouri and Kansas portions of Kansas City.

According to research, in at least 75 percent of cases, businesses would have made the same decision to relocate or expand whether or not incentives were offered by governments.

If a business is considering equally appealing sites and they know that in the local market municipalities play the incentives game, the richer offer might make a marginal difference. However, the deal doesn’t produce a net gain for the region. The attracting jurisdiction forgoes taxes that may actually be needed to offset the increased traffic or demand for public safety protection. Granting one business tax incentives arguably gives that incoming business an advantage over existing local businesses.

To forge consensus and push the process, the Mayor’s Association needed to identify a champion. They found it in Mountain Brook Mayor Stewart Welch. Welch had only been in office two years. He came out of an investment advising and management business. He wasn’t invested in the prevailing political order of things, and he had credibility when talking about business and economics.

Welch reached out to each mayor and worked toward a proposal. The first part of the pledge was easy. The mayors would pledge not to solicit a local business located in a neighboring municipality to move.

It was harder to ask the mayors to give up their tactical weapon.

Welch kept working to convince his fellow mayors that a widely accepted agreement would short-circuit what seemed to be an increasing problem. Expanding businesses within the region were actually motivated to move across municipal lines, because it was expected that they could get incentives to move or, when those incentives were put on the table, they’d get an incentive offer to stay where they were.

Welch worked to convince mayors that it was a counterproductive and unnecessary exercise to incentivize moves that were going to happen regardless. It was a losing proposition for each city and the region, he argued. It diverted resources, time, and attention that should have been spent on bringing in businesses from outside the region, a business that would result in a net gain in employment and population for the region.

While the initial report included a description of the Denver area’s no-poaching Code of Ethics, the Community Foundation provided Welch and the other mayors with additional research support. They helped locate five other similar agreements from around the country and arranged phone conferences between mayors and the individuals in Denver who were involved in crafting the no-poaching agreement there. The mayor of Birmingham provided a staff member’s assistance with the drafting process.

Welch began circulating drafts, and with the other mayors’ input, they moved toward mutually agreeable language. And they came up with a catchy name: “The Good Neighbor Pledge.”

Eventually, 23 cities agreed to sign on, including the eight largest. In sum, the signatories represent about 85 percent of the county population. Even though three sizable suburbs — Irondale, Fultondale, and Gardendale — declined to sign, the “coalition of the willing” moved ahead.

The mayors gathered at the Jefferson County Courthouse to formally sign the agreement with the Jefferson County Commission looking on. The event drew favorable press coverage and continues to inspire further conversation about additional cooperative ventures.

The Good Neighbor Pledge is not a legally binding agreement. It doesn’t have “teeth.”

The mayors are still working on a dispute resolution process that could handle conflicts over the Good Neighbor Pledge if they were to occur.

Going forward, the mayors have discussed increased cooperation on 9-1-1 services. They’ve also discussed creating a comprehensive countywide or even regional listing of available office and commercial space and industrial parks.

Regardless of what is next, it is hoped that the mayors have taken a step toward communication and cooperation in a local landscape that has traditionally been marred by distrust and competition. And they continue to look out for self-interested opportunities to help improve conditions for all.