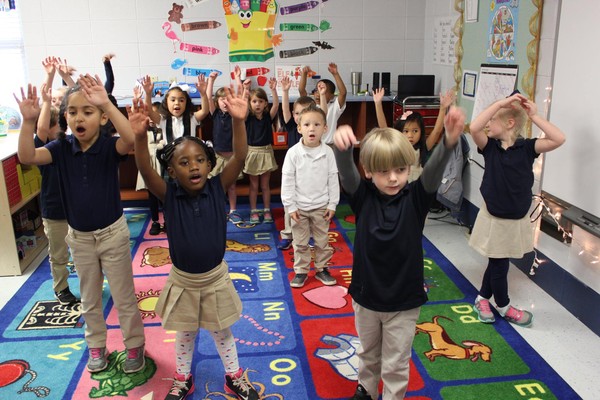

Students who attended the First Class Pre-K program in Alabama are more likely to be proficient in reading and math compared to other students — and this academic advantage persists over time.

This is the key finding of an ongoing study of Alabama First Class Pre-K conducted by researchers from the Public Affairs Research Council of Alabama, the UAB School of Public Health, and the UAB School of Education. This research was funded by the Alabama Department of Early Childhood Education.

Key Findings

- students who received First Class Pre-K were more likely to be proficient in reading and math compared to students who did not receive First Class Pre-K; and

- the academic benefit of First Class Pre-K persisted through the middle school years and did not fade out, or decrease, over time.

These findings add to previous findings that showed students receiving Alabama First Class Pre-K:

- demonstrate higher readiness for kindergarten;

- are less likely to be chronically absent;

- are less likely to be held back a grade; and

- are less likely to need special education services in K – 12

All of these measures produce savings to the education system that recur year after year as students progress through school.

Why is Pre-K Important?

The early years of school through the 3rd grade are a critical time in a child’s brain development. These early years provide a window for developing a foundation for sustained success. Problems that emerge during the early years are more difficult to address later on. High-quality pre-k programs provide opportunities to address gaps in early child development and to improve school readiness.

UAB-PARCA Research

The effectiveness of quality pre-k in preparing students for kindergarten has been well

documented. However, recent studies in other states have suggested the impact of pre-k programs fade away once students are in school, especially in the later grades. In response our UAB-PARCA research team, as part of its on-going assessment, specifically examined whether or not this happens with the Alabama First Class Pre-K program.

We studied three years (2014-15, 2015-16, and 2016-17) of student scores on state reading and math assessments, comparing students who received First Class Pre-K with those who did not receive First Class Pre-K.

We also compared the percent of students who were proficient in reading and math to identify differences between pre-k and non-pre-k students over time. We wanted to know if — after allowing for differences in poverty, race, gender, school attended, and general statewide trends — the academic benefit for students who received First Class Pre-K persisted as the students aged.

Study Findings

The UAB-PARCA team found that students who received First Class Pre-K were more likely to be proficient in reading and math compared to students who did not receive First Class Pre-K, and the benefit of First Class Pre-K persisted over time and did not fade out.

Specifically…

- The percent of students earning a proficient score in reading were 1.6 percentage points higher for students receiving First Class Pre-K than for students who did not receive First Class Pre-K, all else equal, and this difference persisted at least through the middle school years.

- The percent of students earning a proficient score in math were 3.2 percentage points higher for students receiving First Class Pre-K than for students who did not receive First Class Pre-K, all else equal, and this difference persisted at least through the middle school years.

Conclusion

Studies in other states have suggested the academic effects of pre-k are minimal and decline over time. Our study finds this is not the case in Alabama. Similarly, a new study from Duke University finds long-lasting effects of pre-k in North Carolina. These studies indicate that program design and implementation are key to a successful pre-k program.

Students who attended First Class Pre-K are more likely than other students to be proficient in reading and math, all else equal, and this academic advantage continues into at least middle school. These findings show that by making a positive difference in academic proficiency — something highly resistant to positive change — the Alabama First Class Pre-K program is working.